Stronend, Fintry Hills

Double Craigs, Fintry Hills

"On the Battle of

the Miathi

AT another time, after

the lapse of many years from the above-mentioned battle, and while the holy man

was in the Iouan island (Hy, now Iona), he suddenly said to his minister,

Diormit, ‘Ring the bell.’ The brethren, startled at the sound, proceeded

quickly to the church, with the holy prelate himself at their head. There he

began, on bended knees, to say to them, ‘Let us pray now earnestly to the Lord

for this people and King Aidan, for they are engaging in battle at this

moment.’ Then after a short time he went out of the oratory, and, looking up to

heaven, said, ‘The barbarians are fleeing now, and to Aidan is given the

victory; a sad one though it be.’ And the blessed man in his prophecy declared

the number of the slain in Aidan's army to be three hundred and three men.

Prophecy of St. Columba

regarding the sons of King Aidan

At another time, before

the above-mentioned battle, the saint asked King Aidan about his successor to

the crown. The king answered that of his three sons, Artur, Eochoid Find, and

Domingart, he knew not which would have the kingdom after him. Then at once the

saint prophesied on this wise, ‘None of these three shall be king, for they

shall fall in battle, slain by their enemies; but now if thou hast any younger

sons, let them come to me, and that one of them whom the Lord has chosen to be

king will at once rush into my lap.’ When they were called in, Eochoid Buide,

according to the word of the saint, advanced and rested in his bosom.

Immediately the saint kissed him, and, giving him his blessing, said to his

father, ‘This one shall survive and reign as king after thee, and his sons

shall reign after him.’ And so were all these things fully accomplished

afterwards in their time. For Artur and Eochoid Find were not long after killed

in the above-mentioned battle of the Miathi; Domingart was also defeated and

slain in battle in Saxonia; while Eochoid Buide succeeded his father on the

throne."

The Dark Age Miathi

were known to the Romans as the Maeatae. This was a federation of tribes

centered just north of the Antonine Wall, and apparently (given the location of

the hillforts of Myot Hill and Dumyat) more towards the eastern end of the

Wall. We first hear of them causing major trouble in the reign of

Septimius Severus (emperor from 193-211 A.D.).[1] The Caledonians north

of the Wall eventually entered into alliance with them, magnifying the

seriousness of the threat.

The name Maeatae means

possibly 'the larger people', but more probably (see Rivet and Smith's THE

PLACE-NAMES OF ROMAN BRITAIN [2]) 'those of the larger part.'

The Irish sources have Arthur son of

Gabran die in what sound like two different places: in the territory of the

Miathi or, alternately, in Circinn.

There may be yet another

Arthur who can be linked to the Miathi - and this is none other than the most

famous one presented to us in the HISTORIA BRITTONUM. For my best

identification of this hero's Bassas river battle site is Dunipace in Scotland

[3]. Dunipace has the distinction of being found directly between

the two known Miathi forts - Dumyat in Stirling and Myot Hill in

Falkirk. In this context I had once made the tentative suggestion

that the presence of an Arthur at Dunipace may be a confusion over the Dalriadan Arthur fighting in that location.

However, there does not appear to be any relationship between Dunipace and Circinn. In addition, the Circinn of Arthur son of Aedan appears to be in a totally different place than the region of a similar sounding name north of the River Tay in Angus and Mearns.

The most recent good treatment of the subject can be found in James E. Fraser's FROM CALEDONIA TO PICTLAND: SCOTLAND TO 795. Here are a couple of short extracts from that title:

Alan James was kind enough to share this information with me regarding Circinn:

"Watson, CPNS 108, points out that OIr cír is 'a crest', and so cír-chenn is 'a crested head'. That seems more like a personal than a place-name, but Circhind is genitive, so Magh Circhind could be 'Circhen's plain'."

Cirech, on the other hand (according to William J. Watson in THE HISTORY OF THE CELTIC PLACE-NAMES OF SCOTLAND), meant "crested." From the eDIL:

círach

adj o, ā (cír). In phr. cathbarr c.¤ crested helmet: a chathbarr c.¤ clárach, LU 6392 ( TBC-I¹ 1877 ) ( TBC-LL¹ 2533 ). cathbarr c.¤ 'ma chend cechtar nái, RC xiii 456.z . cathbairr ciracha, fororda, Cog. 162.5 . corrc[h]athbharr c.¤ , CCath. 5262 . cathbarr cirrach, YBL 121a45 . Note also: brú . . . / bheannbhachlach chíorach na gcolg (of ship), Measgra D. 48.34 .

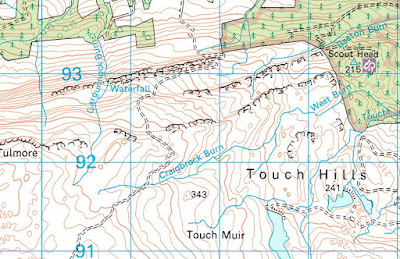

If I had to hazard a guess as to a location for Cirech/Circinn, I would opt for the boundary region between Dunbartonshire and Stirlingshire. When searching the maps and reading relevant descriptions of the area, I noticed the remarkably long escarpment with crags stretching from the Touch Hills in the east to the Fintry Hills in the west. The 'crest' of this escarpment is remarked upon in great detail by the following geological report:

https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/13985/1/RR10007.pdf

"The member is restricted to the Fintry–Touch Block (Francis et al., 1970) and specifically to the western and northern parts of the Fintry Hills, and the northern parts of the Gargunnock and Touch hills. These rocks crop out from the crest of the crags at Double Craig [NS 6365 8701], westwards to Ballmenoch Burn [NS 6485 8692 to 6464 8752], and northwards to the prominent crags below Stronend [NS 6266 8950] which extend eastwards to the Spout of Ballochleam [NS 6526 8998] and on to the north-north-east, below Lees Hill [NS 6587 9106] and east-north-east to Standmilane Craig [NS 6704 9176] and Black Craig [NS 6841 9228]. From there, the outcrop continues to the east, passing through more crags and then to Baston Burn [NS 7437 9374]."

"The Lees Hill Lava Member consists predominantly of trachybasalt but also includes a plagioclase-macrophyric basalt lava (‘Markle’ type), and the rocks generally form the crest of the escarpment at the top of the cliffs formed by the Spout of Ballochleam Lava Member. The trachybasalt is typically fine grained, massive, locally ‘slaggy’ and highly vesicular, and with local platy jointing. A single trachybasalt lava is present in the east [NS 7184 9247], which occurs as an intercalation within the macroporphyritic basalt lavas of the Gargunnock Hills Lava Member, near to its base. In the Gargunnock Burn [NS 7065 9249 to 7059 9222] two trachybasalt lavas are present, separated by a plagioclasemacrophyric basalt lava that is absent farther west, where the member consists entirely of trachybasalt lavas."

"The member is restricted to the northern part of the Fintry–Touch Block (Francis et al., 1970) and specifically to the northern Gargunnock Hills and northern Touch Hills, northeast of Glasgow. These rocks generally form the crest of the escarpment at the top of the cliffs formed by the Spout of Ballochleam Lava Member and crop out northwards from Gourlay’s Burn [NS 6628 8974 to 6625 9003] to Lees Hill [NS 660 910], east-north-east to Standmilane Craig [NS 6722 9180] and Black Craig [NS 6829 9219], and then eastwards through crags to the east of Gargunnock Burn [NS 7195 9244]."

When I discussed this with place-name expert Alan James, he remarked:

"The Gargunnock Hills are more immediately the boundary between the territory of the Miathi and (geographical) Strathclyde, ruled from Alclud. The R Endrick is still the boundary between W Dunbartonshire and Stirlingshire, and I think Fintry may be Brittonic *fin-dre 'boundary settlement' rather than a Gaelicised *(g)win-dre (as is the case with the one in Angus). Dalriada was to the west, across the Ben Lomond range and Loch Lomond. But that part of the Forth valley down to Stirling is the strategic heart of Scotland, anyone wanting to control the north of Britain has to win command of Castle Rock (Stirling) and The Fords of Frew. So battles were always going around there!"

Circinn as the 'crested head' or 'head of the crest' could be Stronend. The first element of this hill-name is Scots-Gaelic strone (https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/strone_n2), "A headland or promontory, esp. one that ends a range or ridge of hills." Double Craigs is also a good candidate.

Crags along the crest of the Fintry Hills

Crags along the crest of the Touch Hills

Crags along the crest of the Gargunnock Hills (and below)

[1]

MAEATAE

Rivet & Smith,

p. 404 :

SOURCE

- Xiphilinus 321

(summarising Cassius Dio LXXVI, 12) : Maiatai (= MAEATAE; twice);

- Jordanes 2, 14 (also

quoting Cassius Dio) : Meatae

DERIVATION. Holder II.

388 thought the name Pictish, and it is discussed by Wainwright PP 51-52; it

may survive in Dumyat and Myot Hill, near Stirling and thus north of the

Antonine Wall. Watson CPNS 58 seems to take the name as wholly Celtic, as is

surely right in view of the Continental analogues he cites for the second

element or suffix : Gaulish Gais-atai 'spearmen' (*gaison 'spear'), Gal-atai

'warriors' (*gal 'valour, prowess'), Nantu-atai (-ates) 'valley-dwellers'; he

notes also the presence in Ireland of the Magn-atai. See also ATREBATES, with

further references. One might therefore conjecture that in this name at least

the force of the suffix is 'those of. . . '. The first element might be the

same as in Maia, probably 'larger', in which case a sense 'larger people' or

more strictly 'people of the larger part' may be suitable. It is to be noted

that Cassius Dio, as quoted by others, seems to say that Britain north of the

Antonine Wall was divided between the Calidonii and the Maeatae, these having

subsumed lesser tribes, and it could well be that the Maeatae were the 'people

of the larger part'. The name was still in use in Adamnan's day : Miathi in his

Life of St Columba, I, 8.

MAIA/MAIUM:

* Rivet & Smith, p.

408 :

SOURCES

- Rudge Cup and Amiens

patera : MAIS

- Ravenna 1075 (=

R&C 120) : MAIO

- Ravenna 10729 (=

R&C 154) : MAIA

- Ravenna 10922

(=R&C 298) : MAIONA

(ND : We propose to

read, at XL49, Tribunus cohortis primae Hispanorum, MAIS (or MAIO); for the

argument, see p. 221)

In his 1935 study of the

Rudge Cup, Richmond noted that Bowness fort was the terminal point of two

Systems, the Wall and the Cumbrian coastal defences, and was therefore

mentioned twice by Ravenna (which, he then thought, rarely repeated names). The

association of Ravenna's Maiona with this place is made here for the first

time. Although at 10922 it figures in the list of islands ad aliam partem, and

was taken as a western island by R&C, it is likely that (as is the case

with other non-island names in this section) it was written 'in the sea' on a

map and wrongly interpreted by the Cosmographer. Final -na could have arisen

from *Maium (neuter singular) on the map, written as was the Cosmographer's

habit *Maion and then miscopied.

DERIVATION. It is not

sure what the correct form of this name in Latin guise should be. The only

epigraphic evidence indicates a locative plural in -is (as argued also for the

Rudge Cup form of Camboglanna). If this is right, the nominative neuter plural

of the name is Maia, as in Ravenna I0729. In that case the neuter singular Maio

and what we can see in Maiona are equally acceptable oblique-case singulars.

All may be right; such variation in recorded forms is by no means improbable.

R&C suggests that

the base of the name is British *maios, comparative of *maros (compare Latin

maior), from which Welsh mwy derives; Jackson LHEB 357 and 360 appears to

accept this. The sense is therefore 'larger (one or ones)', perhaps referring

to the size of promontories (Bowness contrasted with Drumburgh). If thename is

basically adjectival, it is easy to see how in differing interpretations it

could be singular or plural, as the sources appear to show. The root is

represented in personal names in Gaul such as Maiagnus, Maianus, Maiiona for

*Magiona (Holder II. 387), perhaps Maiorix; in Gaul and Italy a goddess Maia

was known. The only relevant place-names abroad seem to be Maio Meduaco between

Brenta Vecchia and Brentella in N. Italy, and the Statio Maiensis mentioned

under Magis. The North British Maeatae people may have a first element in their

name corresponding to the present name.

[2]

19 1 In the eighteenth

year of his reign, now an old man and overcome by a most grievous disease, he

[Severus] died at Eboracum in Britain, after subduing various tribes that

seemed a possible menace to the province.

https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Historia_Augusta/Septimius_Severus*.html#note136

5 4 Inasmuch as the Caledonians

did not abide by their promises and had made ready to aid the Meaetae, and in

view of the fact that Severus at the time was devoting himself to the

neighbouring war, Lupus was compelled to purchase peace from the Maeatae for a

large sum; and he received a few captives.

https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/76*.html

12 1 There are two

principal races of the Britons, the Caledonians and the Maeatae, and the names

of the others have been merged in these two. The Maeatae live next to the

cross-wall which cuts the island in half, and the Caledonians are beyond

them.

5 1 When the inhabitants

of the island again revolted, he [Severus] summoned the soldiers and ordered

them to invade the rebels' country, killing everybody they met; and he quoted

these words:

"Let no one escape

sheer destruction,

No one our hands, not

even the babe in the womb of the mother,

If it be male; let it

nevertheless not escape sheer destruction."

2 When this had been

done, and the Caledonians had joined the revolt of the Maeatae, he began

preparing to make war upon them in person. While he was thus engaged, his

sickness carried him off on the fourth of February, not without some help, they

say, from Antoninus.

https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/cassius_dio/77*.html

[3]

Place-name expert Alan James again

came to the rescue when I asked how Bassas may have developed out of Late Latin

or Late Brittonic:

“By the time the Latin word was

adopted by Britt speakers, its inflectional forms were probably quite reduced

at least in "vulgar" speech, and the Britt inflextions likewise. So

your hypothetical form would be, for practical purposes *bassas. The -as suffix

is nominal, noun-forming, it would be 'a shallow, shallows'. I suppose that

might be a stream-name, more likely a name for a stretch of a river or a point

on a river or estuary, a strategic location where a battle might well be

fought, though of course there must be scores of possible candidates.”

Long ago the antiquarian Skene

suggest Dunipace ner Falkirk in Stirlingshire for Arthur’s Bassas. The idea has

not been thought well of by scholars over the years. However, recently

place-name expert John Reid has tentatively proposed that Dunipace might be

rendered Dun y Bas, the ‘Hill of the Ford.’

Commenting on this possibility, Alan

James shared this with me:

“It ought to be *din-y-bas, not

**dun-y-bais (that's what misled me); it would mean more correctly 'fort of the

shallow', which is apparently okay topographically; the changes din > dun,

/b/ > /p/, and /a/ > long /a:/ could all be explained in terms of

adoption by Gaelic speakers. 'Hills of death' [a local, traditional etymology]

would be G *duin-am-bais, which I wouldn't rule out, though I'm uneasy with

/mb/ > /p/.”

.JPG)