Tuesday, May 29, 2018

Sunday, May 27, 2018

THE LIDDINGTON BADBURY AND ARTHUR THE HERO

The Badburys

In a recent blog post, I suggested that the date for Arthur's Badon is not only wrong, but very much so. My idea, simply put, is that what we find in the work of Gildas is a later interpolation. Whoever inserted the statement regarding the date of Badon, which coincidentally (or providentially?) happened to fall on the very day the saint was born, wrongly identified it with the ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE BATTLE of 501 at Portsmouth, one of the combatants of whom was Bieda.

From Wikipedia of the name Bieda:

"As a masculine given name, it originates as an Anglo-Saxon short name, West Saxon Bīeda, Northumbrian Bǣda, Anglian Bēda (the purported name of one of the Saxon founders of Portsmouth in AD 501 according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle)[1] cognate with German Bodo."

[Source citation is J. Insley, "Portesmutha" in: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde vol. 23, Walter de Gruyter (2003), 291.]

According to Dr. Richard Coates,

"There are many mysteries about AS GNs. Many are of totally obscure origin, and this might be one of them. Its stem appears homonymous with the stem of the ‘prayer’ word bedu, but that has a short vowel whilst that in Beda is long. I can see no phonological argument to derive it from beadu (< Proto-Gmc *badu-) unless by some mysterious hypocoristic process. The same applies to Be:da and be:odan, 'to command.'. It’s not out of the question that there is a hypocorism of some sort involved, but it would be non-standard. Redin gives a complicated etymology which amounts to 'I don’t really know.'"

By establishing this very early date for Badon, the interpolator has seriously thrown off all subsequent writers - right up to the modern era. My choice for the Battle of Badon - in this case, a decisive action fought at Liddington Castle in Wiltshire - is fought sometime soon after the Barbury/Bear's Fort battle in 556 A.D. From that time up to the next failed penetration of Wiltshire (the slaughter at Adam's Grave) just under 40 years will pass. Someone based in that specific region had successfully kept the Saxons and their Gewissei allies at bay for that entire period. For a more complete accounting of this remarkable defense of tribal territory, see http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/05/arthur-and-beranburhbarbury-critical.html.

Now, the question I wish to address here in some detail is whether it might really be possible for such an interpolation to have occurred in the DE EXCIDIO. I've many times discussed the very real possibility that Badon could represent a Badbury. To quote from Dr. Richard Coates' "Middle English badde and Related Puzzles" (NOWELLE, Vol. 11, February 1988):

"We must conclude that whilst one of the Badburys may be the historical site of Badon, this may not be safely inferred from the linguistic evidence within English (pace Jackson 1953b). The inference requires the rather casual association of a form [baðón] with the recurrent name-type Baddanburh; there can be no direct etymological connection."

That the latter may well have happened is at least suggested by the apparent identification of the Second Battle of Badon in the WELSH ANNALS with an ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE military action that took place near Liddington Castle/Badbury. I have described this seeming correspondence at http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/05/the-second-battle-of-badon.html.

The best we can do with Badon linguistically is to say that it would be the normal British rendering of Anglo-Saxon Bathum. No Celtic derivation - attempted by anyone - has passed muster. Curiously, there is a similar problem inherent in etymologizing Baddan-, which must come from a Badda, an attested personal name (e.g. a moneyer during the reign of Edward the Elder). For the source of this name, Coates eventually defaults to an unattested OE *badde, the presumed ancestor of ME badde, our modern "bad". According to Coates,

"Its sense in names cannot be determined with precision, but it is not likely to have been very far removed from the present-day senses of the word bad. One might guess at 'worthless', 'of ill omen or repute', 'disgusting', since all these meanings appear in the first century of the word's history."

While Coates makes a good argument, when one actually looks at the more impressive Badbury hillforts, it is difficult to see anything "bad" about them.

Badbury Rings, Dorset

Liddington Castle, Badbury, Wiltshire

They are incredibly impressive, monumental structures. If anything, they are places of awe - and I imagine they would have been exactly that to the Dark Age invaders of England. How exactly would badde have been used pejoratively for either such a structure or those great enough to have constructed it - or even those who much later still resided within it or used it for tactical advantage? While maligning or dehumanizing one's enemy is an expected application of a psychological tool during warfare, it seems decidedly odd that we would call this kind of superior fort "badde" and not refer to him in the same way! I'm not aware of the Welsh being disparaged this way in the ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE. Instead, I'm reminded of the Briton, 'a very noble man', who is slain in 501 A.D. He is not called a 'badde' man, or said to be hunkered down in a 'badde' place.

Rather, I feel fairly strongly that Coates was right when he says "...Badda... could have been a hypocoristic form of the more flattering Beadu- names." Beadu is listed thusly in Bosworth and Toller's dictionary:

BEADO, beadu; g. d. beadowe, beadwe, beaduwe; f. Battle, war, slaughter, cruelty; pugna, strages :-- Gúþ-Geáta leód, beadwe heard the War-Goths' prince, brave in battle, Beo. Th. 3082; B. 1539. Wit ðære beadwo begen ne onþungan we both prospered not in the war, Exon. 129b; Th. 497, 2; Rä. 85, 23. Beorn beaduwe heard a man brave in battle, Andr. Kmbl. 1963; An. 984. Ðú þeóde bealdest to beadowe thou encouragest the people to slaughter, Andr. Kmbl. 2373; An. 1188. [O. H. Ger. badu-, pato-: O. Nrs. böð, f. a battle: Sansk. badh to kill.]

For the earlier Germanic root, here is the listing from http://www.bulgari-istoria-2010.com/Rechnici/A_Lyubotski_Proto_Germanik_dict.pdf:

*badwo- f. 'battle' - ON poet bpa, gen. -var f. 'id.', OE beado f. 'id.', OS badu

'id.', 'OHG batu- 'id.' => *bhodh-uehz- (WEUR) - Identical to Mir. bodb, badb

m./f. 'war-god(dess); scald-crow', OBret bodou 'heron' < *bhodh-uo/eh2-.

A Celtic-Germanic isogloss.

For the earlier Germanic root, here is the listing from http://www.bulgari-istoria-2010.com/Rechnici/A_Lyubotski_Proto_Germanik_dict.pdf:

*badwo- f. 'battle' - ON poet bpa, gen. -var f. 'id.', OE beado f. 'id.', OS badu

'id.', 'OHG batu- 'id.' => *bhodh-uehz- (WEUR) - Identical to Mir. bodb, badb

m./f. 'war-god(dess); scald-crow', OBret bodou 'heron' < *bhodh-uo/eh2-.

A Celtic-Germanic isogloss.

If Badda does represent a beadu- name, then the various Badbury forts are the "Battler's forts" or the like. I would compare such to the several British Cadbury place-names. Quite some time ago I wrote this blog article:

Please give that piece a thorough perusal, and note especially Dr. Coates' comments in response to some of my more salient queries. In brief, I proposed that the Badbury forts are the English equivalent of the British Cadburys, in that both series of fort names are fronted by pet-forms of a battle name in their respective languages. And, furthermore, that Gildas's 'stragis' for Badon is, more or less, a Latin attempt to render the meaning of this pet name.

Let us assume, then, that Badda is, indeed, a hypocorism for a Beadu- name. Does this help make any more acceptable the notion that the 501 A.D. Portsmouth battle featuring Bieda (Beda, Baeda) may have been misidentified with a later Baddan- battle? Well, again, not strictly from a linguistic point of view. But if we allow for a "rather casual association" of the names Bieda (or a variant) and Badda, then I really don't see why such a misidentification could not have happened.

If it did happen - and I grant that this is a big "if" - Arthur would have been catapulted back in time a full generation. And we would once more have to take a serious look at Uther Pendragon/Illtud as his father. Illtud's "Llydaw" must be a descriptor of the broad valley of the Usk at Brecon, which seems to have been the traditional home of the warrior-turned-saint. The kingdom of Brycheiniog was founded by the Irish, and because the other Arthurs of the same time period all belonged to Irish-descended dynasties in Britain, Illtud of Brycheiniog as Arthur's father would allow us to account for this fact. Eoin MacNeil (see http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/01/the-solution-to-llydaw-problem.html) postulates that Ui Liathain were in on the settlement of Brycheiniog, and the Ui Liathain were the enemies of the Ciannachta, i.e. Cunedda and his sons or teulu.

To opt instead for Illtud as hailing from the Vale of Leadon (a river-name deriving from the same root as that found in Llydaw), which had once been part of the Dobunni kingdom, we would lose the needed Irish connection. As Barbury and Liddington were themselves in Dobunni lands, it is tempting to seek another way of tying Arthur to the Irish. Unfortunately, I have not found a means of doing so. Yet it cannot be denied that an Illtud and an Arthur from the old Dobunni lands seems an especially nice fit. Please see http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/12/arthur-dobunni-and-hwicce.html for a comparison of the Dobunni and Hwicce kingdoms.

Cerdic of the Gewissei (= Ceredig son of Cunedda) would not be Arthur at all, an idea I promoted in my recent book THE BEAR KING. Instead, he would merely be one of the enemy allies of the English who were repeatedly sent against Arthur. The Gewissei were Irish or Hiberno-British mercenaries or "federates" who fought for the High King of Wales against fellow Britons to the south. I've shown that there is a serious problem with the chronological order of the battles or of the participants in those battles as recorded in the ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE, for the generations of the Gewissei are found REVERSED in the English source. In other words, the Cunedda pedigree as found in the Welsh sources runs BACKWARDS in the ASC. So who exactly Arthur may have faced, as well as when and where, is not easy to determine.

The only thing I can say about an Arthur at Barbury Castle is that he "fits the mold" of the heroic British king defending his people against the pagan invaders. If there were such a man at this place and in this time, he probably died at the Camlan I've tentatively identified with the Uley Bury hillfort in Gloucestershire. Where he was buried we will probably never know. A real 'Avalon' may have been just across the Mouth of the Severn from Uley Bury at Lydney Park (*Nemetabala or 'Sacred Apple Grove'?), about which I've written some articles:

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/12/the-apple-bearing-ash-tree-of-mirabilia.html

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/01/the-lydney-park-temple-of-nodens-as.html

However, the best candidate for the site of his grave would be the famous nemeton at West Hill next to Uley itself:

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/01/the-archaeological-phases-of-uley.html

So, the question is: CAN WE ALLOW FOR ARTHUR BEING WRONGLY PLACED EARLY IN THE SIXTH CENTURY WHEN HE PROPERLY BELONGS TO THE MID AND LATER PORTION OF THAT CENTURY? If we staunchly adhere to the traditional chronology, obviously not. But when we do that, we find ourselves without an identifiable Arthur, and without a verifiable theater of action for him to operate in. We find ourselves cast adrift in an endless landscape of uncertainties, where everything - and nothing - is possible. I've chased Arthur (and my own tail) for many years now, all the while confining myself to the conventionally accepted 516-537 A.D. floruit. What I discovered is that there is no independent supportive material whatsoever for Chapter 56 of the HISTORIA BRITTONUM or for the two, terse entries of the ANNALES CAMBRIAE. I had looked over and over again for some previously unperceived revelation in the English sources, and even the Continental ones. But until I "disenthralled myself" and dared to think outside the box of the established time constraints, I could make no headway.

The case for Cerdic/Ceredig of the Gewissei as Arthur is, in many ways, a compelling one. Yet it is also in many ways woefully deficient and unsatisfying. And not only because Ceredig son of Cunedda is not, really, the Arthur we want. It is because if we don't make a serious effort to explain the inability of the English and the Gewissei to take Wiltshire for something like 40 years we are doing a profound injustice to whoever it was who had managed to protect the inheritors of the Dobunni kingdom from its enemies.

For if the man of the Bear's Fort was not Arthur, WHO WAS? Or, perhaps we should say, WHO MORE DESERVED TO BE?

Note that I do not expect any professional Arthurian scholar to acknowledge this latest theory of mine as something viable. Quite the contrary. Still, I feel compelled to "put it out there", if for no other reason than to satisfy myself that I have left no stone unturned in my pursuit of whatever truth is actually available to us.

If it did happen - and I grant that this is a big "if" - Arthur would have been catapulted back in time a full generation. And we would once more have to take a serious look at Uther Pendragon/Illtud as his father. Illtud's "Llydaw" must be a descriptor of the broad valley of the Usk at Brecon, which seems to have been the traditional home of the warrior-turned-saint. The kingdom of Brycheiniog was founded by the Irish, and because the other Arthurs of the same time period all belonged to Irish-descended dynasties in Britain, Illtud of Brycheiniog as Arthur's father would allow us to account for this fact. Eoin MacNeil (see http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/01/the-solution-to-llydaw-problem.html) postulates that Ui Liathain were in on the settlement of Brycheiniog, and the Ui Liathain were the enemies of the Ciannachta, i.e. Cunedda and his sons or teulu.

To opt instead for Illtud as hailing from the Vale of Leadon (a river-name deriving from the same root as that found in Llydaw), which had once been part of the Dobunni kingdom, we would lose the needed Irish connection. As Barbury and Liddington were themselves in Dobunni lands, it is tempting to seek another way of tying Arthur to the Irish. Unfortunately, I have not found a means of doing so. Yet it cannot be denied that an Illtud and an Arthur from the old Dobunni lands seems an especially nice fit. Please see http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/12/arthur-dobunni-and-hwicce.html for a comparison of the Dobunni and Hwicce kingdoms.

Cerdic of the Gewissei (= Ceredig son of Cunedda) would not be Arthur at all, an idea I promoted in my recent book THE BEAR KING. Instead, he would merely be one of the enemy allies of the English who were repeatedly sent against Arthur. The Gewissei were Irish or Hiberno-British mercenaries or "federates" who fought for the High King of Wales against fellow Britons to the south. I've shown that there is a serious problem with the chronological order of the battles or of the participants in those battles as recorded in the ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE, for the generations of the Gewissei are found REVERSED in the English source. In other words, the Cunedda pedigree as found in the Welsh sources runs BACKWARDS in the ASC. So who exactly Arthur may have faced, as well as when and where, is not easy to determine.

The only thing I can say about an Arthur at Barbury Castle is that he "fits the mold" of the heroic British king defending his people against the pagan invaders. If there were such a man at this place and in this time, he probably died at the Camlan I've tentatively identified with the Uley Bury hillfort in Gloucestershire. Where he was buried we will probably never know. A real 'Avalon' may have been just across the Mouth of the Severn from Uley Bury at Lydney Park (*Nemetabala or 'Sacred Apple Grove'?), about which I've written some articles:

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/12/the-apple-bearing-ash-tree-of-mirabilia.html

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/01/the-lydney-park-temple-of-nodens-as.html

However, the best candidate for the site of his grave would be the famous nemeton at West Hill next to Uley itself:

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/01/the-archaeological-phases-of-uley.html

So, the question is: CAN WE ALLOW FOR ARTHUR BEING WRONGLY PLACED EARLY IN THE SIXTH CENTURY WHEN HE PROPERLY BELONGS TO THE MID AND LATER PORTION OF THAT CENTURY? If we staunchly adhere to the traditional chronology, obviously not. But when we do that, we find ourselves without an identifiable Arthur, and without a verifiable theater of action for him to operate in. We find ourselves cast adrift in an endless landscape of uncertainties, where everything - and nothing - is possible. I've chased Arthur (and my own tail) for many years now, all the while confining myself to the conventionally accepted 516-537 A.D. floruit. What I discovered is that there is no independent supportive material whatsoever for Chapter 56 of the HISTORIA BRITTONUM or for the two, terse entries of the ANNALES CAMBRIAE. I had looked over and over again for some previously unperceived revelation in the English sources, and even the Continental ones. But until I "disenthralled myself" and dared to think outside the box of the established time constraints, I could make no headway.

The case for Cerdic/Ceredig of the Gewissei as Arthur is, in many ways, a compelling one. Yet it is also in many ways woefully deficient and unsatisfying. And not only because Ceredig son of Cunedda is not, really, the Arthur we want. It is because if we don't make a serious effort to explain the inability of the English and the Gewissei to take Wiltshire for something like 40 years we are doing a profound injustice to whoever it was who had managed to protect the inheritors of the Dobunni kingdom from its enemies.

For if the man of the Bear's Fort was not Arthur, WHO WAS? Or, perhaps we should say, WHO MORE DESERVED TO BE?

Note that I do not expect any professional Arthurian scholar to acknowledge this latest theory of mine as something viable. Quite the contrary. Still, I feel compelled to "put it out there", if for no other reason than to satisfy myself that I have left no stone unturned in my pursuit of whatever truth is actually available to us.

The Uley Temple

Tuesday, May 22, 2018

REVISITING MY TWO FAVORITE CANDIDATES FOR CAMLANN

However, I have also looked at another, perhaps more exciting potential site: the Uley Bury hillfort in Gloucestershire.

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/12/uley-bury-and-arthurs-camlan-process-of.html

After extensive searching, I've not found additional suitable places in southern England.

In this blog post, I will try to decide if Uley Bury is the more viable candidate of the two widely separated locations.

To begin, it is fairly obvious that if Arthur fought at Badon, and Badon is (as linguistics demand) Bath in Somerset, then we must invoke a new chronology, one that it very difficult to establish, as it would be based solely on the misordering of the Gewissei genealogy - something evinced in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. See

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/05/the-gewissei-and-cuneddas-sons-why-are.html

Furthermore, as Camlann was Arthur's last battle, it plainly followed Badon. When we look at the taking of Bath in the ASC, an action which Cerdic's/Ceredig's father Ceawlin/Maquicoline/Cunedda supposedly spear-headed, and then place on the map the other battles and sites mentioned in the year 577, as well as battles subsequent to Dyrham in 584 at Fethanleag and in 592 at Adam''s Grave - with Ceawlin dying at an undisclosed location* in 593 - the resulting map is rather telling. For Uley Bury and the River Cam are right in the middle of the grouping.

Uley Bury and Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Battles

Does this mean Arthur died at Uley Bury? Well, we have a choice, as I see it. Either Ceredig/Cerdig/Arthur went home from his southern battles and died fighting a neighboring dynast in Merionethshire at the Afon Gamlan - something certainly possible, as Ceredigion and Merionethshire bordered upon each other - or Camlann as *Cambolanda, the Crooked Enclosure or Enclosure of the Cam [River], was part of a continuing Gewissei campaign in Gloucestershire.

My problem with the Afon Gamlan in NW Wales is that it is a rather unremarkable site for a battle. The Roman road does not even cross it. On the other hand, there is no denying the impressive nature of the Uley Bury hillfort, and hillforts were targeted by the Gewissei. Uley Bury is also smack-dab in the middle of the Gewissei military theater. For these reasons alone I would prefer Uley Bury as Arthur's Camlann.

*Crida perishes along with Ceawlin. If we may allow for this to be a form of Creoda/Creda, Ekwall mentions a 'Creodan hyll' in Wiltshire. So far as I know, the hill has not been identified. But it could be that Ceawlin/Cunedda died at this place.

Monday, May 21, 2018

Coming Soon: REVISITING MY TWO FAVORITE CANDIDATES FOR CAMLANN

Uley Bury Hillfort, Gloucestershire

The Welsh tradition, as I've discussed before in posts and in my book THE BEAR KING, places Arthur's last and fatal battle on the Afon Gamlan in Gwynedd.

However, I have also looked at another, perhaps more exciting potential site: the Uley Bury hillfort in Gloucestershire.

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/12/uley-bury-and-arthurs-camlan-process-of.html

After extensive searching, I've not found additional suitable places in southern England.

In the next blog post, I will try to decide between my two favorite candidates - the Afon Gamlan and Uley Bury.

THE GEWISSEI AND CUNEDDA'S SONS: WHY ARE THE GENERATIONS REVERSED IN WELSH AND ENGLISH SOURCES?

Cerdic of the Gewissei

Ever since I was able to identify the the leaders of the Gewissei with Cunedda and his son, I was aware of the strange and somewhat unaccountable fact that the line of descent for these Irish or Hiberno-British "federates" was reversed in the ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE. Until now, however, I'd not really had the chance to consider what this reversal might actually mean. Obviously, it creates a major chronological problem for the list of ASC battles featuring the Gewissei.

Precedence must be given to the order established in the early British sources. It is impossible, as far as I'm concerned, for the Welsh to have gotten the order of the Cunedda dynasty backwards. That they did not is supported by the inscription of the Cunorix Stone at Wroxeter, where Cunorix/Cynric is the son of Cunedda/Maquicoline/Ceawlin (for my identification of Ceawlin with Cunedda Maquicoline, see my book THE BEAR KING and related blog posts). In the ASC, it is implied that Ceawlin is the son of Cynric.

Here is the order of the princes of the Gewissei, from both the Welsh and English sources:

Welsh: Hyddwyn (from hydd, stag, hart) son of Cerdic son of Cunedda Maquicoline

Iusay (= Gewis/sei/sae) son of Cerdic son of Cunedda M.

Cunorix son of Cunedda M.

English: Ceawlin (=Cunedda) son of (?) Cynric son of Cerdic son of Elesa/Esla (conflated with Aluca/Aloc from the Bernician pedigree), also Elafius, 'stag, hart', son of Gewis (eponym for the Gewissei)

The question that faces us, given this reversal of the Gewissei peidgree, is quite simply (and profoundly!) this: if Cunedda and his sons appear in reverse order in the ASC, are we to rearrange them in accordance with the order of the battles set down in that source or, even more radically, should the battle order itself be flipped on its head? In other words, do we maintain the battles as they are presented to us, and suggest only that the wrong leaders are assigned to them? Do we assume Cunedda and his sons all fought together and that some were present at various battles, even if their names are not to be found in this or that year entry? Or do we go even further and propose that some or all of the battles from 495 (the advent of Cerdic) to 593 (the death of Ceawlin) should be considered an incorrect and possibly artificial arrangement?

Let us take the 577 ASC entry, for example. This is when Ceawlin supposedly took Bath. Over the years, I've taken great pains to show (by utilizing the expertise of top Celticists around the world) that Badon, as found in Gildas, and Caer Faddon/Vaddon of the later Welsh sources, linguistically has to be Bath. That is, Badon is the regular British spelling for English Bathum. However, we could not demonstrate that the generally accepted date for the Battle of Badon in the Welsh Annals, c. 516 (or c. 500 +/- 10-20 years) made any sense at all. From what we know through archaeology and sources such as the ASC, a battle at Bath (even if we allow this to be the other bathum/batham in the North at Buxton) against the English this early was not possible. The English had not gotten anywhere near as far west at Bath by this early date.

Yet we must bear in mind that it is Ceawlin/Maquicoline/Cunedda who took Bath, according to the ASC. P.C. Bartram places the "migration" of Cunedda and his sons to NW Wales at c. 430. More recently, John Koch has suggested c. 400 as the migration date, or a "heyday" for Cunedda in the later 5th century. Other dates have been proposed, but the consensus is that Cunedda's floruit was the 5th century NOT, AS THE ASC WOULD HAVE US BELIEVE, THE 6TH CENTURY. The Cunorix Stone was dated by Wright and Jackson between 460-475 A.D., although they also added that it could belong anywhere between the beginning of the 5th century and the middle of the 6th.

I suspect, therefore, that the Welsh Annals date of c. 516 A.D. is correct, and this was the Battle of Bath in Somerset. That Ceawlin/Maquicoline/Cunedda was present, as was his son Cerdic, whom I've identified as Arthur in THE BEAR KING. Of course, this means that Cerdic/Arthur was not fighting the English at all, but rather was allied with the English against the British at Bath. And these Britons were enemies of the High King of Wales, for whom the Gewissei were acting as federates or mercenaries.

While this solution to the 'Badon Problem" seems elegant enough, it does throw into total disarray the other battles of the ASC. We must also accept the fact that Cerdic's death in 537, according to the ASC, matches very closely Arthur's death at Camlan in 537. We are not told where Cerdic dies.

Sunday, May 20, 2018

Saturday, May 19, 2018

WAS UTHER PENDRAGON REALLY ARTHUR'S FATHER?

Uther Pendragon in John Boorman's "Excalibur"

Although I am confident of my identification of Uther Pendragon with St. Illtud, the question remains: was he really Arthur's father?

Information on Uther prior to Geoffrey of Monmouth's fictional HISTORY OF THE KINGS OF BRITAIN is scarce. To quote from the entry on Uther in P.C. Bartram's A CLASSICAL WELSH DICTIONARY:

UTHR BENDRAGON, father of Arthur. (445) ‘U. Chief Warleader’. Evidence that Uthr Bendragon was known to the Welsh before the time of Geoffrey of Monmouth is plentiful, but it does not tell us much about the pre-Geoffrey legend. He is mentioned in the poem ‘Who is the porter’ in the Black Book of Carmarthen, a dialogue between Arthur, Cai and Glewlwyd Gafaelfawr. Mabon ap Modron, one of the companions of Arthur, was guas Uthir Pendragon, ‘Servant of Uthr Bendragon’ (BBC 94, ll.6-7). An early triad (TYP no.28) tells of the Enchantment of Uthr Bendragon as being one of the ‘Three Great Enchantments’ of Ynys Prydain, and says that he taught the enchantment to Menw ap Teirgwaedd. In the Book of Taliesin (BT 71) there is a poem entitled Marwnat Vthyr Pen to which Dragon has been added in the margin in a later hand. This expansion is probably justified, since, among much that is obscure, the poem contains a reference to Arthur: ‘I have shared my refuge, a ninth share in Arthur's valour’ (BT 71, 15-16). See AoW 53. All these references bring Uthr into the Arthurian orbit (TYP p.521). Madog ab Uthr is mentioned in the Book of Taliesin (BT 66) and Eliwlod ap Madog ab Uthr is described as nephew of Arthur in a poem which shows no dependence on Geoffrey of Monmouth. See s.nn. Eliwlod, Madog. This is evidence that Uthr was regarded as father of Arthur in pre-Geoffrey legend. In two manuscripts of the Historia Brittonum (Mommsen's C, L, 12th and 13th centuries), §56, which lists Arthur's battles, contains a gloss after the words ipse dux erat bellorum: Mab Uter Britannice, id est filius horribilis Latine, quoniam a pueritia sua crudelis fuit, ‘In British Mab Uter, that is in Latin terrible son, because from his youth he was cruel’. According to Professor Jarman there is here a deliberate pun on the word uthr, which can be either an adjective (‘terrible’) or a proper name. The author of the gloss could have been familiar with Geoffrey of Monmouth's ‘Historia’. See A.O.H.Jarman in Llên Cymru, II (1952) p.128; J.J.Parry in Speculum, 13 (1938) pp.276 f. See further TYP pp.520-3.

The most important phrase in this entry is "This is evidence that Uthr was regarded as father of Arthur in pre-Geoffrey legend." The context is the 'Dialogue' poem. Unfortunately, as Professor Patrick Sims-Williams discusses in his "The Early Welsh Arthurian Poems" (in THE ARTHUR OF THE WELSH), the 'Dialogue' is preserved only in fourteenth century or later MSS., but may be as early as the twelfth century. Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote his HISTORY c. 1138, i.e. in the first half of the 12th century. Thus there is no way we can know whether the 'Dialogue' poem was influenced by Geoffrey's claim that Arthur's father was Uther Pendragon.

The reference to Arthur in the Uther elegy is, like many lines of this poem, difficult and obscure. Here are the relevant lines and accompanying note from Marged Haycock's recent translation:

13. Neu vi a rannwys vy echlessur:

It was I who shared my stronghold:

14. nawuetran yg gwrhyt Arthur.

Arthur has a [mere] ninth of my valour.

Note to Line14

nawuetran yg gwrhyt Arthur

Nawuetran ‘ninth part’ with yg gwrhyt understood as ‘of my valour’ (gwryt ~ gwrhyt). Arthur has a ninth part of the speaker’s valour. This seems to have more point than ‘I have shared my refuge, a ninth share in Arthur’s valour’, TYP3 513, AW 53. Gwrhyt ‘measure’ is not wholly impossible — ‘one of the nine divisions [done] according to the Arthurian measure/fathom’, etc., or ‘a ninth part is in [a place] called Arthur’s Measure or Span’, the latter like Gwrhyt Kei discussed TYP3 311, and other Gwryd names discussed G 709-10. The phrase is exactly the same as in §18.30 (Preideu Annwfyn) tra Chaer Wydyr ny welsynt wrhyt Arthur.

This is no way implies Arthur is Uther's son. As I've mentioned before, Arthur here may be the usual paragon of military virtue to whom Uther is being compared, much as the warrior Gwawrddur is compared (unfavorably) to Arthur in Line 972 of the "Goddodin." Yet someone like Geoffrey of Monmouth may have come across this 'death-song' and decided to use it as the exceedingly slender basis for making Uther Arthur's father.

Nothing in the VITA of St. Illtud suggests that he was Arthur's father. In fact, it is pointedly stated in that hagiographical work that Illtud is Arthur's cousin. So if Illtud were Arthur's father, the fact was later altered in the tradition which preferred to make of this terrible warrior a Christian saint.

All in all, the evidence in support of Uther as Arthur's father is quite poor. Yet if we dispense with him, we are left with no father at all for Arthur. We must admit that either his father was unknown or that the identify of his real father was, for some reason, concealed.

Thursday, May 17, 2018

Illtud, Father of Arthur, and the Llydaw/"Brittany" of Brycheiniog

Brecon Gaer Roman Fort, Photo Courtesy COFLEIN

Readers of my past blogs will know that I've proposed several "Llydaws" as the home of Illtud/Uther Pendragon, the reputed father of Arthur.

As any father of Arthur has to have proven Irish heritage, I had dispensed with those theories that did not fulfill this condition.

Two possibilities remained. 1) Illtud was not from Llydaw/"Brittany", but was of the Ui Liathain of SE Ireland. I showed how Llydaw could have been mistakenly substituted for Liathain. However, the idea is made difficult by two facts. First, we would have to account for the change in the terminal letter from /n/ to /w/ (or perhaps /u/ or /f/). This happens, under certain circumstances. And while we have several instances of Liathain being written in a form that could more easily allow it to be mistaken for something like Welsh llydan, there is no doubt that the two words are NOT related.

From Professor Jurgen Uhlich at the Department of Irish and Celtic languages, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland:

"These are actually two different words that cannot be confused: líath, gen. sg. m. léith, etc., has an original long ē, while the -e- of lethan is short, < *i and corresponding to Gaul. litano- etc. Ui Liathain is thus for Ui Líatháin, with the common suffix -án, and the Primitive Irish equivalent would be, written in Ogam, *LETAGNI, i.e. nothing to do with ‘broad’, which would have given *Ui Lethain < *LETANI lowered from *LITANI. The reported reading in CIIC no. 273 is actually ‘LIT[ENI]’, which could not be ‘broad’ either, and Macalister’s sketch appears to read LITOVI instead (though perhaps meant to be damaged, i.e. two dots might be intended to be missing for an E, and one stroke for an N). So in short, the ía strictly rules out your proposed equation."

Because of these problems, I looked again to the prevailing view (as evinced, for example, in P.C. Bartram's A CLASSICAL WELSH DICTIONARY) that this particular Llydaw was to be found in Wales - and, in particular, somewhere in the vicinity of the Brycheiniog where we find two supposed graves for Illtud. The saint was said to have been buried in Letavia/Llydaw, so the fact that we find two prehistoric tombs bearing his name to the west and east of Brecon is surely significant.

One grave is near Defynnog and Mynydd Illtud, the Bedd Gwyl Illtud or Grave of Illtud's Festival, and the other is Ty Illtud or House of Illtud north of Llanhamlach.

I decided to see how Llydaw (from a Celtic root meaning 'broad' or 'wide') could possibly refer to this region. What I found, rather surprisingly, were many references to the BROAD valley of the River Usk at Brecon. While I could cite all of these, I hope the following will suffice. It is drawn from Charles Thomas's AND SHALL THESE MUTE STONES SPEAK?, which discusses the Irish-founded kingdom of Brycheiniog in some detail.

"The centre [of the Kingdom of Brycheiniog] is modern Brecon, at the south end of the broad corridor between mountains running north-north-east up to the river Wye at Glasbury."

In other words, the Usk Valley was unusually wide or broad at this point, and the Welsh word llydaw (from a well-attested Celtic root meaning wide or broad or extensive) may well have been applied to it as a descriptive term, which in time came to be confused for an actual place-name.

Having read these many references to the wide valley of the Usk at Brecon, and having viewed photos and studied topographical maps, I'm now convinced that this location is, in fact, the "Llydaw" of Illtud. And, having reached this conclusion, I can now say that as a man of Brycheiniog, he most likely had Irish blood in his veins. If he were, in actuality, the father of Arthur - as tradition insists - then we can account for the fact that the name Arthur was later used only for royal sons of Irish-descended dynasties in Britain.

Wednesday, May 16, 2018

Monday, May 14, 2018

GILDAS AND THE DATE OF THE MOUNT BADON BATTLE

Solsbury Hill

Many scholars have written about Gildas's dating of the Battle of Badon. The history of this lively debate is best found summarized, and dealt with, in

Thomas D. Sullivan, THE DE EXCIDIO OF GILDAS: ITS AUTHENTICITY AND DATE, 1978, pp. 134-157 (link courtesy Professor Marek Thue Kretschmer):

https://books.google.no/books?id=q2U3i1X8B50C&pg=PA155&dq=%22let+us+turn+back+now+to+the+badonic+question%22&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiqt5ng54PbAhXGDSwKHbvUDlEQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=%22let%20us%20turn%20back%20now%20to%20the%20badonic%20question%22&f=false

An even more recent treatment of the date of Badon can be found here:

https://people.clas.ufl.edu/jshoaf/2014/07/07/gildas/

An even more recent treatment of the date of Badon can be found here:

https://people.clas.ufl.edu/jshoaf/2014/07/07/gildas/

The consensus, plainly, is that the Battle of Badon happened when Gildas was born, i.e. 44 years ago, with one month of that 44th year having already passed at the time of his writing. According to P.C. Bartram (A CLASSICAL WELSH DICTIONARY), Gildas was born c. 490 A.D.. Other scholars put his birth date closer to 500 A.D. or even into the second decade of the 6th century.

I asked Professor Alexander Andrée, Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto, whether another reading of the DE EXCIDIO passage on Badon and Gildas's birth might be possible:

"Could he [Gildas] be writing about the battle a month after the battle took place, a battle which, as it happened, had fallen exactly 44 years after he had been born?"

To which the Professor responded:

"The crucial passage is “mense iam uno emenso,” literally translating as, “with one month already having been measured out.” But the word “iam” may be translated in a host of different ways: already, at last, by this time, just, etc. So, yes, I would say that there is a certain ambiguity about the passage. Maybe translating it as you suggest is stretching it little too far, but I wouldn’t say it’s entirely impossible.

It is an unfortunately dense passage. I don’t have any stakes in the question and would translate the passage, “… quique quadragesimus quartus (ut noui) orditur annus mense iam uno emenso, qui et meae natiuitatis est,” as, “… and which year, the 44th <year> as I know it, began with one month already having passed, which is also <the year> of my birth.”"

From Professor Gernot Wieland:

"Here is a literal translation of the passage in question:

quique quadragesimus quartus (ut noui) orditur annus mense iam uno emenso, qui et meae natiuitatis est

"which begins the forty-fourth year (as I know) with one month already having passed, which is also (the year) of my birth."

The first and second "which" refers to the "annus" of the battle of Mount Badon. In other words, the Battle of Mount Badon began the year which is now in its forty-fourth year.

Since no "dies" = "day" is mentioned, and since the "qui" in "qui et meae natiuitatis est" must refer to "annus," a birthday must be ruled out,

So, no matter how I turn the phrase, I always come up with the same conclusion: the battle took place forty-four years and one month ago, and forty-four years ago is also the year of Gildas birth. And to answer your question directly: I see no way that he could be writing about the battle one month after it took place, nor is there any indication that the battle took place on his forty-fourth birthday, since no "day" is mentioned."

The opinion of Professor Els Rose:

"I gather that you relate qui ... est to mense rather than annus, which is a possibility, although I would be inclined to link the relative pronoun to the subject of the preceding clause rather than to the noun in the ablative absolute. Also, with the sequence sed ne nunc the narrative seems to create a distance from the period of the battle of Badon Hill and the time of writing, so that it would make sense to place that battle in a more or less distant past (the period of the author's birth)."

Professor Michael Herren, who has actually worked on the text, has a somewhat different take on the correct translation of the problematic passage:

"Ex eo tempore [from that time] nunc cives, nunc hostes vincebant [now our citizens, now our enemies were victorious] -- ut in ista gente expireretur dominus solito more praesentem Israelem, utrum diligat eum an non -- [ -- so that the Lord might test in his people the present Israel in his accustomed way, (as to) whether it loves him or not--] usque ad annum obsessionis Badonici montis novissimaeque ferme de furciferis non minimae stragis [to the year of the siege of Mount Badon and almost the last but not least carnage involving those rogues], quique quadragesimus quartus (ut novi) orditur annus mense uam uno emenso [which year begins already the 44th less one month] qui et meae nativitatis est [and also the year of my birth].

Paraphrase: From that time (indefinite) when things were going this way and that (that the Lord blah blah) to the Battle of Mount Badon, which was nearly the last one with those villains, is, as I know, 44 years less one month.

The time is counted as 44years less a month from some unspecified time (ex eo tempore) to (usque ad) the Battle of Mt. Badon, which happens to coincide with the year of Gildas's birth. An exact parsing of the syntax (which I sent you; see above) bears this out.

Incidentally, the Welsh Annals give the Battle of Badon as 516 C.E., which would mean that G. was 44 in that year, and would have been born in 472. If the Annals are right, he was writing in 516 or some time afterwards. However, scholars are sceptical of annalistic dates before the 7th century.

See Thomas D. O'Sullivan'sstudy, The De Excidio: Its authenticity and date (Brill, 1978), last chapter. O'S. takes the eo tempore as a reference to the victory of Ambrosius Aurelianus."

From Professor Gernot Wieland:

"Here is a literal translation of the passage in question:

quique quadragesimus quartus (ut noui) orditur annus mense iam uno emenso, qui et meae natiuitatis est

"which begins the forty-fourth year (as I know) with one month already having passed, which is also (the year) of my birth."

The first and second "which" refers to the "annus" of the battle of Mount Badon. In other words, the Battle of Mount Badon began the year which is now in its forty-fourth year.

Since no "dies" = "day" is mentioned, and since the "qui" in "qui et meae natiuitatis est" must refer to "annus," a birthday must be ruled out,

So, no matter how I turn the phrase, I always come up with the same conclusion: the battle took place forty-four years and one month ago, and forty-four years ago is also the year of Gildas birth. And to answer your question directly: I see no way that he could be writing about the battle one month after it took place, nor is there any indication that the battle took place on his forty-fourth birthday, since no "day" is mentioned."

The opinion of Professor Els Rose:

"I gather that you relate qui ... est to mense rather than annus, which is a possibility, although I would be inclined to link the relative pronoun to the subject of the preceding clause rather than to the noun in the ablative absolute. Also, with the sequence sed ne nunc the narrative seems to create a distance from the period of the battle of Badon Hill and the time of writing, so that it would make sense to place that battle in a more or less distant past (the period of the author's birth)."

Professor Michael Herren, who has actually worked on the text, has a somewhat different take on the correct translation of the problematic passage:

"Ex eo tempore [from that time] nunc cives, nunc hostes vincebant [now our citizens, now our enemies were victorious] -- ut in ista gente expireretur dominus solito more praesentem Israelem, utrum diligat eum an non -- [ -- so that the Lord might test in his people the present Israel in his accustomed way, (as to) whether it loves him or not--] usque ad annum obsessionis Badonici montis novissimaeque ferme de furciferis non minimae stragis [to the year of the siege of Mount Badon and almost the last but not least carnage involving those rogues], quique quadragesimus quartus (ut novi) orditur annus mense uam uno emenso [which year begins already the 44th less one month] qui et meae nativitatis est [and also the year of my birth].

Paraphrase: From that time (indefinite) when things were going this way and that (that the Lord blah blah) to the Battle of Mount Badon, which was nearly the last one with those villains, is, as I know, 44 years less one month.

The time is counted as 44years less a month from some unspecified time (ex eo tempore) to (usque ad) the Battle of Mt. Badon, which happens to coincide with the year of Gildas's birth. An exact parsing of the syntax (which I sent you; see above) bears this out.

Incidentally, the Welsh Annals give the Battle of Badon as 516 C.E., which would mean that G. was 44 in that year, and would have been born in 472. If the Annals are right, he was writing in 516 or some time afterwards. However, scholars are sceptical of annalistic dates before the 7th century.

See Thomas D. O'Sullivan'sstudy, The De Excidio: Its authenticity and date (Brill, 1978), last chapter. O'S. takes the eo tempore as a reference to the victory of Ambrosius Aurelianus."

These kinds of responses, as it turned out, were kind and generous. Of over a dozen top experts in Medieval Latin I consulted on this question, all leaned heavily on the prevailing interpretation, i.e. that Gildas was born on the day of the battle. And that means Badon happened c. 500, +/- 10-20 years.

Some responses, on the other hand, were quite terse. For example:

"The Latin doesn’t say that. It says the battle happened in the same year that he was born." [Professor Robert Babcock]

We can try to argue, without justification, that an error of transmission occurred during some phase of the copying of the MS., but this is something we cannot prove. It would be merely a wild guess, in fact, and a totally insupportable one at that.

But I believe I have found a way out of our difficulty.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle mentions a battle being fought in 501 A.D. A chieftain involved in the battle was named Beida (West Saxon Bīeda, Northumbrian Bǣda, Anglian Bēda). Beida's name is preserved in Bedenham on Portsmouth Harbour.

What I'm going to propose, rather boldly, is that Gildas's 'Badon' originally was the battle featuring Bieda/Beda. Now, let me hasten to add this does not mean I'm saying Arthur's Badon is a fiction or is based on an otherwise rather inconsequential battle at Portsmouth.

Instead, I'm suggesting that the REAL Badon, Arthur's Badon, i.e. Bath of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for the year 577 (see my book THE BEAR KING: ARTHUR AND THE IRISH IN WALES AND SOUTHERN ENGLAND), was at some point in the transmission of manuscripts wrongly substituted for the Beden- battle of Gildas.

It is only purists who will object to this idea. Although Gildas (and other early sources, such as the HISTORIA BRITTONUM) have been subjected to merciless criticism in the modern era, there are still those who hold to the idea that the veracity of Gildas's DE EXCIDIO is to be upheld. This despite major problems with the text, such as the inclusion of Ambrosius Aurelianus (who, as I have shown in detail elsewhere, was a 4th century figure). People clinging to this kind of of inflexible view will never be able or willing to accept the idea that Badon was wrongly related to the Portsmouth battle of 501 A.D. They will continue to look for Arthur where he does not exist, precisely because they have temporally dislocated him.

I suspect many philologists will also object to the notion. They will insist that Bieda/Baeda/Beda place-name cannot have been mistaken for Bath. Well, this may be true in our time, when our knowledge of the languages involved and their development has become so advanced. But in the ancient period sound-alike etymology and fanciful etymology were common practices. Add to this the difficulty of going from English to Welsh (or to Irish) and I do not think this kind of confusion is that unlikely. I would add in concluding that Badon, as it stands, is still - speaking from a strictly linguistic standpoint - a British version of English Bathum, and as such may have been thought of by the Welsh as Bath.

Sunday, May 13, 2018

THE SECOND BATTLE OF BADON

Alfred's Castle, Ashdown

[NOTE: The following is taken from an old post of mine at http://www.facesofarthur.org.uk/articles/guestdan2.htm.]

There is one possible clue to identifying Badon. It lies in a comparison of the Welsh Annals entry for the Second Battle of Badon and the narrative of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The actual year entry for this Second Battle of Badon reads as follows:

665 The first celebration of Easter among the Saxons. The second battle of Badon. Morgan dies.

The "first celebration of Easter among the Saxons" is a reference to the Synod of Whitby of c. 664. While not directly mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, nor the Anglo-Saxon version of Bede, there is an indirect reference to this event:

664 … Colman with his companions went to his native land…

This is, of course, a reference to Colman's resigning of his see and leaving Lindisfarne with his monks for Iona. He did so because the Roman date for Easter had been accepted at the synod over the Celtic date.

While there is nothing in the ASC year entry 664 that helps with identifying Badon, if we go to the year entry 661, which is the entry found immediately prior to 664, an interesting passage occurs:

661 In this year, at Easter, Cenwalh [King of Wessex] fought at Posentesburh, and Wulfhere, son of Penda [King of Mercia], ravaged as far as [or "in", or "from"] Ashdown…

So, we have:

1) Easter, Badon

2) Easter, ravaging as far as or in or from Ashdown

So, we have:

1) Easter, Badon

2) Easter, ravaging as far as or in or from Ashdown

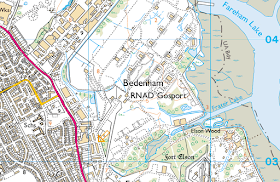

Ashdown is here the place of that name in Berkshire. It is only a half dozen miles to the east of Badbury and Liddington Castle and about twice that distance to the south of Badbury Hill fort. A vague reference to ravaging in the neighborhood of Ashdown may well have been taken by someone who knew Badon was in the vicinity of Ashdown as a second battle at Badon. As the Mercian king was raiding into Wessex, it is entirely conceivable that his path took him through Liddington/Badbury or at least along the Roman road that ran immediately to the east of the area.

Ashdown's Proximity to Liddington Castle/Badbury and Badbury Hill

I've recently identified Posentesbyrig as "Pascent's Burg". Leading English place-name authority Dr. Richard Coates had this to say when I asked him if this etymology worked:

"I see no absolute barrier to Posent – Pascent. Welsh <sc> is the cluster [sk], which would be rendered in OE as “esh” since OE had no cluster [sk] before a front vowel, even in the earliest times. “Esh” would normally also be spelt <sc>, but that’s a coincidence. It’s possible for “esh” to appear very occasionally as <s>, even before the conquest, as in Ryssebroc for Rushbrooke (Suffolk) in the mid-10th century."

Unfortunately, we have no way of knowing where Pascent's Burg was located. Pascent son of Vortigern ruled over Buellt and Gwrtheyrnion. But the Vortigern family was also said to have originated at Gloucester. William of Malmesbury seems to suggest (although this is unclear from his text; see http://www.dot-domesday.me.uk/wessex.htm) that Bradford on Avon was once called Vortigern's Burg, but this is surely not right, as Cenwalh of Wessex is said to fight at both Bradford on Avon and Posentesbyrig in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. While Pascent's Burg and Vortigern's Burg may refer to the same place, if these aren't nicknames for Gloucester we cannot know Posentesbyrig's location.

The battle listed before Posentesbyrig in the ASC is Peonnum, fought against the Welsh by Cenwalh. This is thought to be Penselwood in Somerset, found in the Domesday Book as Penne or Penna.

A battle at Gloucester, nicknamed Pascent's fort, would make sense between the Mercian king Wulfhere and the Wessex king Cenwalh.

A battle at Gloucester, nicknamed Pascent's fort, would make sense between the Mercian king Wulfhere and the Wessex king Cenwalh.

According to Nennius' HISTORIA BRITTONUM, Chapter 49:

Chapter 49. This is the genealogy of Vortigern, which goes back to Fernvail, who reigned in the kingdom of Guorthegirnaim, and was the son of Teudor; Teudor was the son of Pascent; Pascent of Guoidcant; Guoidcant of Moriud; Moriud of Eltat; Eltat of Eldoc; Eldoc of Paul; Paul of Meuprit; Meuprit of Braciat; Braciat of Pascent; Pascent of Guorthegirn; Guorthegirn of Guortheneu; Guortheneu of Guitaul; Guitaul of Guitolion; Guitolion of Gloui. Bonus, Paul, Mauron, Guotelin, were four brothers, who built Gloiuda, a great city upon the banks of the river Severn, and in British is called Cair Gloui, in Saxon, Gloucester.

Thus it would seem a good case can be made for identifying Posentesbyrig with Gloucester.

Thursday, May 10, 2018

Arthur and Beranburh/Barbury: A Critical Reexamination of the Possible Significance of the Bear's Fort in Wiltshire

Barbury Castle, Wiltshire

From time to time in the past I'd speculated about a possible connection between Arthur and Barbury Castle, the "Bear's fort", in Wiltshire. Nothing much ever came of this speculation, however - but only perhaps because I did not push it far enough. I will attempt to redress this deficiency here.

The year entry for Beranburh/Barbury in the ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE occurs in 556 - that is before the entry for the death of Ida.

Now, let us imagine that Nennius (or whoever compiled the HISTORIA BRITTONUM) had inserted his Arthurian material between the rise of Hengist's successor and end of Ida's reign. If so, then both Arthur, whose name was surely related by the Welsh to their own word arth, 'bear', and a Bear's fort battle would be found bracketed by the same annalistic events. In fact, one could go so far as to say that the writer of the HB knew the bear at Barbury was none other than Arthur! Or, at the very least, he chose to identify a war-leader named Arthur with this particular bear.

Bearing all this in mind (pun strictly intended!), let us take a close look at the historical sequence in the ASC. Once we have analyzed that, I wish to go over the dating of the Battle of Badon as it is derived from the testimony of Gildas and the Welsh Annals.

Let us look at the early battles in Wiltshire as these are found recorded in THE ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE. We begin with the defeat of the British by Cynric at Old Sarum in 552. Four years later a battle is fought at Barbury Castle further north. However, this battle is, significantly, not said to be a victory. We are merely told there was a battle there. In 560, Ceawlin succeeds Cynric (see my earlier work for the reversal of the genealogical links for the Gewissei in the ASC). After Barbury Castle there are no more battles against the Britons until 571 - 15 years later. And the theater of action has changed: the Gewissei are now coming up the Thames Valley. In 577, the war theater changes again - this time to the west and north of Wiltshire (including the capturing of Bath). In 584, there is a battle in Oxfordshire, well to the NE of Wiltshire. We do not return to Wiltshire until 592, when a great slaughter occurs at Adam's Grave near Alton Priors resulting in the expulsion of Ceawlin. In the next year, Ceawlin perishes.

From the Battle of Beranburh to that of Adam's Grave, 36 years had passed. Adam's Grave is roughly 15 kilometers south of Barbury Castle.

The question I would put forth is simply this: who was in Wiltshire for all this time keeping the Gewissei and the English out? And is it a coincidence that only several kilometers NE of Barbury Castle along the ancient Ridge Wayt is the Liddington Badbury fort?

I have argued before that the Gewissei battles could be nothing more than an antiquarian attempt to define the boundaries of the nascent kingdom of Wessex. But if that is so, why are there defeats suffered in Wiltshire?

As I've remarked before, I do not have a problem with one of the Badbury forts being Badon - as long as we recognize that philologically Badon = Bath. In other words, we would have to accept the possibility that Badon (British form of English Bathum) was wrongly substituted for a Baddan-. This is a problem only for modern philologists and need not be applied to early medieval chroniclers.

As for the name of Barbury, it is indisputably English. The Gewissei who fought there were Irish or Hiberno-British. The enemy of the Gewissei at this fort were Britons. So we can be certain that the name of the place is an anachronism. The English only later came to refer to the fort as belonging to 'The Bear'. We have no idea what it's original British name might have been. A personal English name Bera is not recorded in English, according to Ekwall (see his entry for Barham, Kent, in THE CONCISE OXFORD DICTIONARY OF ENGLISH PLACE-NAMES).

Going on the account of battles in the ASC, there appears to have been some kind of very strong British resistance centered in Wiltshire, an area where we not only find a Bear's fort, and a Badbury, but a place called Durocornovium (near Nythe Farm,Wanborough). Some attempt has been made to prove that this is a "ghost site", and that the name as we have it is a corruption of the Roman name for Cirencester, i.e. Corinium (Dobunnorum). I do not find this last argument at all convincing. In the words of Rivet and Smith (THE PLACE-NAMES OF ROMAN BRITAIN), "the nearest major Iron Age settlement [to Durocornovium] is at Liddington Castle, 3 and a half miles to the south." R&S render the name 'fort of the Cornovii people.'

However, the name may refer to a topographical feature. My guess would be the situation of Upper Wanborough, which lies between Nythe Farm and Liddington Castle. From http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol9/pp174-186:

"Geographically the parish is divided roughly in half, the southern section lying on the chalk downs. The shape of the parish conforms to a pattern found along the scarp slope of the Chalk both westwards into Wiltshire and eastwards into Berkshire, each parish having chalk uplands as well as greensands and clays for meadow and pasture. (fn. 7) Upper Wanborough, around the church, is on an Upper Greensand spur commanding a view north over Lower Wanborough and south over Liddington. The northern half of the parish towards the shallow valley of the River Cole is successively Gault, Lower Greensand, and Kimmeridge Clay. (fn. 8) The chalk scarp rises behind the village, reaching 800 ft. at Foxhill on the parish boundary. Most of the Chalk lies between 600 ft. and 700 ft. Two coombs pierce the eastern boundary between the Ridge Way and the Icknield Way, the larger containing two chalk pits. Below the scarp the land falls gently away to the river, to below 300 ft., and is drained by the Cole, its tributary stream the Lidd [for which Liddington was named], and several smaller streams, providing abundant meadow land and marsh. There is little wood in the parish, although there is evidence of illegal felling during the 16th century. (fn. 9) Stone was quarried at Berrycombe in the 16th century (fn. 10) and marl was taken from Inlands at least from the end of the 13th century. (fn. 11)"

A spur of land or a section jutting out between two coombs could be construed as a "horn of land" and so Cornovium may have been used here in the same sense as it was for Cornwall (Cernyw).

The interesting thing about the place-name is that Arthur in Welsh tradition - to emphasize this point yet again! - is pretty much always associated with Cornwall.

For the sake of argument, then, let us assume for a moment that Arthur belonged at the Bear's Fort/Barbury Castle, and that he stemmed the tide of English and Gewissei invasion for over three decades. If this is so, how do we deal with the serious, and indeed, fatal problem of chronology?

The consensus is that Gildas was born c. 500 A.D. (although P.C. Bartram says c. 490). The date of Badon, which he claims happened on the day of his birth, is thought to be c. 500 +/- 10-20 years. There really is no way to more firmly calculate the date. Even the Badon date of the Welsh Annals has been disputed, primarily on the basis of a difference in the interpretation of calculated Easter Tables and the like. Generally, a date spread of 510-20 is preferred.

Needless to say, this date range cannot be reconciled with a Liddington Castle/Badbury/"Badon" battle that may have been fought sometime shortly after that of Barbury in 556. Unless, of course, we can make a case for the Gildas passage having been garbled/mangled or even deliberately tampered with. There is the tendency to rely on Gildas's account, since he was a contemporary. But Gildas's work is not without its very significant shortcomings. One of these is the inclusion of Ambrosius Aurelianus as a British war-leader. I have been able to show that this tradition is in error: A.A. is a reflection of the Gaulish governor of that name, perhaps conflated with his son, St. Ambrose. Neither were ever in Britain fighting the Saxons (although read: https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2020/05/why-ambrosius-aurelianus-was-put-in.html). Ambrosius' association with Amesbury (as evinced in his being placed at Wallop Brook in the HISTORIA BRITTONUM in a battle against Vortigern's grandfather) has to do with an incorrect identification of the name Ambrosius with a British Ambirix at Amesbury (see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/06/ambirix-as-name-preserved-in-place-name.html).

Let us suppose this happened: the original passage stated that the Battle of Badon had happened on Gildas's 44th birthday - not on the day he was born 44 years and one month ago. If Gildas were born in 510-20, 44 years would put the Battle of Badon somewhere between the years 554 and 564. Remember that the Barbury battle took place in 556.

Had this error occurred early enough in MSS. of Gildas, the word of the saint would have been considered incontrovertible and sources such as the Welsh Annals would automatically merely reckon from his date of birth rather than from his 44th birthday. And hence the date of the Battle of Badon was temporally dislocated, making it impossible to pinpoint it geographically or determine its military context. [Although see below under the detailed discussion regarding the Battle of Badon, and the associated Endnote, for an alternate possibility - one involving the confusion of three different similarly spelled place-names and the odd reversal of the generations for the Gewissei in the Welsh and English sources.]

We would still have to figure out what to do with Arthur's battles. Probably they are to be identified much as I did in THE BEAR KING - with one big difference. Arthur and Cerdic with his Gewissei would be adversaries at those battle-sites, and we would be confronted with the problem of both sides proclaiming victory during the various engagements.

NOTE ON UTHER PENDRAGON AND AN ARTHUR OF BARBURY CASTLE

In past blogs, I demonstrated convincingly that Uther, the only personage ever said to be the famous Arthur's father, was none other than St. Illtud (b. c. 470 according to P.C. Bartram). I decided against Illtud as the actual father of Arthur for several reasons, but chiefly because I opted for a candidate for Arthur who didn't fit into the Dobunni (or Hwicce) model.

In past blogs, I demonstrated convincingly that Uther, the only personage ever said to be the famous Arthur's father, was none other than St. Illtud (b. c. 470 according to P.C. Bartram). I decided against Illtud as the actual father of Arthur for several reasons, but chiefly because I opted for a candidate for Arthur who didn't fit into the Dobunni (or Hwicce) model.

But I've recently had good reason to doubt my earlier conclusion. A recent blog piece written on this subject nicely sets out the difficulty I face when seeking to forsake Illtud for someone else:

The principal problem concerns the perfect correspondence between the Bicknor-Lydbrook origin for Illtud when compared to Bican Dyke-Lydbrook. I have tried my best to ignore this, and to sweep it under the intellectual rug. But it continues to nag at me and I feel that I ignore it at my own peril.

If we accept Illtud as Arthur's father, and an Arthur centered at Durocornovium, which fulfulls the traditional Cornish view of Arthur, we must yet again delve into the Arthur battles in a Southern theater.

THE ARTHURIAN BATTLES IN THE SOUTH

Liddington Castle, Wiltshire - Site of the Battle of Badon?

First, the battles of Arthur:

Mouth of the River Glein

4 battles on the Dubglas River in the Linnuis region

River Bassas

Celyddon Wood

Castle Guinnion

City of the Legion

Tribruit river-bank

Mt. Agned/Mt. Breguoin (and other variants)

Mt. Badon c. 516

Camlann c. 537

And, secondly, those of Cerdic of the Gewessei (interposed battles by other Saxon chieftains are in brackets):

495 - Certicesora (Cerdic and Cynric arrive in Britain)

[Bieda of Bedenham, Maegla, Port of Portsmouth]

Certicesford - Natanleod or Nazanleog killed

[Stuf, Wihtgar - Certicesora]

Cerdicesford - Cerdic and Cynric take the kingdom of the West Saxons

Cerdicesford or Cerdicesleag

Wihtgarasburh

537 - Cerdic dies, Cynric takes the kingship, Isle of Wight given to Stuf (of Stubbington near Port and opposite Wight) and Wihtgar

As Celtic linguist Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson pointed out long ago, 'Glein' means 'pure, clean.' It is Welsh glân. However, there is also a Welsh glan, river-bank, brink, edge; shore; slope, bank. This word would nicely match in meaning the -ora of Certicesora, which is from AS. óra, a border, edge, margin, bank. If we allow for Glein/glân being an error or substitution for glan, then the mouth of the Glein and Certicesora may be one and the same place.

Ceredicesora or "Cerdic's shore" has been thought to be the Ower near Calshot. This is a very good possibility for a landing place. However, the Ower further north by Southampton must be considered a leading contender, as it is quite close to some of the other battles.

Natanleod or Nazanleog is Netley Marsh in Hampshire. The parish is bounded by Bartley Water to the south and the River Blackwater to the north. Dubglas is, of course, 'Black-stream/rivulet.' Kenneth Jackson in his ‘Once Again Arthur’s Battles’ (Modern Philology, Vol. 43, No. 1, Aug., 1945, pp. 44-57) says of the Dubglas:

"Br. *duboglasso-, 'blue-black' which seems confused in place-names with Br. *duboglassio-, OW. *dubgleis, later OW. Dugleis, 'black stream'..."

Linnuis contains the British root for lake or pool, preserved in modern Welsh llyn. Netley is believed now to mean 'wet wood or clearing', and this meaning combined with the 'marsh' that was present probably accounts for the Linnuis region descriptor of the Historia Brittonum.

W. bas, believed to underlie the supposed river-name Bassas, meant a shallow, fordable place in a river. We can associate this easily with Certicesford/Cerdicesford, modern Charford on the Avon. Just a little south of North and South Charford is a stretch of the river called “The Shallows” at Shallow Farm. These are also called the Breamore Shallows and can be as little as a foot deep. An Anglo-Saxon cemetery was recently uncovered at Shallow Farm:

“A Byzantine pail, datable to the sixth century AD, was discovered in 1999, in a field near the River Avon in Breamore, Hampshire. Subsequent fieldwork confirmed the presence there of an early Anglo-Saxon cemetery. In 2001, limited excavation located graves that were unusual, both for their accompanying goods and for the number of double and triple burials. This evidence suggests that Breamore was the location of a well-supplied ‘frontier’ community which may have had a relatively brief existence during the sixth century. It seems likely to have had strong connections with the Isle of Wight and Kent to the south and south-east, rather than with communities up-river to the north and north-east.” [An Early Anglo-Saxon Cemetery and Archaeological Survey at Breamore, Hampshire, 1999–2006, The Archaeological Journal

Volume 174, 2017 - Issue 1, David A. Hinton and Sally Worrell]

Cerdicesleag contains -leag, a word which originally designated a wood or a woodland, and only later came to mean a place that had been cleared of trees and converted into a clearing or meadow. I once thought the Celidon Wood could have been substituted for this site, but that really made no sense. Hardley, Hampshire, being the 'hard' wood (Watts, etc.), looked promising, if we could assume the Welsh knew Celidon (from Calidon-) derived from a British root similar to Welsh caled, 'hard.' But we couldn't assume that.

Instead, Celidon, being a great forest in Pictland, is a mistaken reference to Netley. While the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s insistence on this being named for a British king Natanloed is untrue (Natan- here being wrongly converted into a personal name; it is actually from a root meaning “wet”; see Watts, Mills, Ekwall, etc.), given that the Welsh knew of the famous Pictish Nechtans, in Welsh Neithon or similar (cf. Bede’s Naiton, Naitan), it is probable that the name was identified with a Pictish king and the wood thus relocated to the far North. And, in fact, it is possible that Natanleod/Natanleag in the Linnuis or ‘Lake’ region may have reminded the chronicler of the Dark Age battle of Nechtansmere

(https://canmore.org.uk/site/34664/nechtansmere), which took place at the loch or mire which existed at modern Dunnichen, Scotland, until it was drained in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Castle Guinnion is composed of the Welsh word for 'white', plus a typical locative suffix (cf. Latin -ium). Wihtgar as a personage is an eponym for the Isle of Wight. Wihtgarasburh is, then, the Fort of Wihtgar. But it is quite possible Wiht- was mistaken for OE hwit, 'white', and so Castellum Guinnion would merely be a clumsy attempt at substituting the Welsh for the English. /-gar/-garas/ may well have been linked to Welsh caer, 'fort, fortified city', although the presence of -burh, 'fort, fortified town' in the name may have been enough to generate Castellum. Wihtgara is properly Wihtwara, 'people of Wight', the name of the tribal hidage. Wihtgarasburh is traditionally situated at Carisbrooke.

Arthur's City of the Legion battle may well be an attempt at the ASC's Limbury of 571, whose early forms are Lygean-, Liggean- and the like. The Waulud’s Bank earthwork is at Limbury. Incidentally, Ceawlin’s Wibbandun of 568 is most likely a hill (dun) in the vicinity of Whipsnade, ‘Wibba’s ‘piece of land/clearing, piece of woodland’ (see Ekwall). Whipsnade is under 10 kilometers southwest of Limbury and is on the ancient Icknield Way next to Dunstable Downs.

According to Kenneth Jackson (_Once Again A thur's Battles_, MODERN PHILOLOGY, August,

1945), Tribruit, W. tryfrwyd, was used as an a jective, meaning "pierced through", and some-times as a noun meaning "battle". His rendering of traeth tryfrwyd was "the Strand of the Pierced or Broken (Place)". Basing his statement on the Welsh Traeth Tryfrwyd, Jackson said that "we should not look for a river called Tryfwyd but for a beach." However, Jackson later admitted (in The Arthur of History, ARTHURIAN LITERATURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES: A COLLABORATIVE HISTORY, ed. by Roger Sher-man Loomis) that "the name (Traith) Tribruit may mean rather 'The Many-Coloured Strand' (cf. I. Williams in BBCS, xi [1943], 95).

Most recently Patrick Sims-Williams (in The Ar-thur of the Welsh, THE EARLY WELSH ARTHURIAN POEMS, 1991) has defined traeth tryfrwyd as the "very speckled shore" (try- here being the intensive prefix *tri-, cognate with L. trans). Professor Sims-Williams mentions that 'trywruid' could also mean "bespattered [with blood]." I would only add that Latin litus does usually mean "seashore, beach, coast", but that it can also mean "river bank". Latin ripa, more often used of a river bank, can also have the meaning of "shore".

The complete listing of tryfrwyd from The Dictionary of Wales (information courtesy Andrew Hawke) is as follows:

tryfrwyd

2 [?_try-^2^+brwyd^2^_; dichon fod yma fwy

nag un gair [= "poss. more than one word here"]]

3 _a_. a hefyd fel _e?b_.

6 skilful, fine, adorned; ?bloodstained; battle,

conflict.

7 12g. GCBM i. 328, G\\6aew yg coryf, yn toryf,

yn _tryfrwyd_ - wryaf.

7 id. ii. 121, _Tryfrwyd_ wa\\6d y'm pria\\6d

prydir, / Trefred ua\\6r, treul ga\\6r y gelwir.

7 id. 122, Keinuyged am drefred _dryfrwyd_.

7 13g. A 19. 8, ymplymnwyt yn _tryvrwyt_

peleidyr....

7 Digwydd hefyd fel e. afon [="also occurs as

river name"] (cf.

8 Hist Brit c. 56, in litore fluminis, quod vocatur

_Tribruit_; 14 x CBT

8 C 95. 9-10, Ar traethev _trywruid_).

Tryfrwyd itself, minus the intensive prefix,

comes from:

brwyd

[H. Grn. _bruit_, gl. _varius_, gl. Gwydd. _bre@'t_

`darn']

3 _a_.

6 variegated, pied, chequered, decorated, fine;

bloodstained; broken, shattered, frail, fragile.

7 c. 1240 RWM i. 360, lladaud duyw arnam ny

am dwyn lleydwyt - _urwyt_ / llauurwyt escwyt

ar eescwyd.

7 c. 1400 R 1387. 15-16, Gnawt vot ystwyt

_vrwyt_ vriwdoll arnaw.

7 id. 1394. 5-6, rwyt _vrwyt_ vrwydyrglwyf rwyf

rwyd get.

7 15g. H 54a. 12.

The editors of GCBM (Gwaith Cynddelw

Brydydd) take _tryfrwyd_ to be a fem. noun =

'brwydr'. They refer to Ifor Williams, Canu Anei-rin

294, and A.O.H. Jarman, Aneinin: Y

Gododdin (in English) p. 194 who translates

'clash', also Jarman, Ymddiddan Myrddin a Tha-liesin,

pp. 36-7. Ifor Williams, Bulletin of the

Board of Celtic Studies xi (1941-4) pp. 94-6 sug-gests

_try+brwyd_ `variegated, decorated'.

On brwydr, the National Dictionary of Wales has

this:

1 brwydr^1^

2 [dichon ei fod o'r un tarddiad a@^

_brwyd^1^_, ond cf. H. Wydd. _bri@'athar_ `gair']

3 _eb_. ll. -_au_.

6 pitched battle, conflict, attack, campaign,

struggle; bother, dispute, controversy; host, ar-my.

7 13g. HGC 116, y lle a elwir . . . y tir gwaetlyt,

o achaus y _vrwyder_ a vu ena.

7 14g. T 39. 24.

7 14g. WML 126, yn dyd kat a _brwydyr_.

7 14g. WM 166. 32, _brwydreu_ ac ymladeu.

7 14g. YCM 33, llunyaethu _brwydyr_ a oruc

Chyarlymaen, yn eu herbyn.

7 15g. IGE 272, Yr ail gofal, dial dwys, /

_Brwydr_ Addaf o Baradwys.

7 id. 295.

7 1567 LlGG (Sall) 14a, a' chyd codei _brwydyr_

im erbyn, yn hyn yr ymddiriedaf.

7 1621 E. Prys: Ps 32a, Yno drylliodd y bwa a'r

saeth, / a'r _frwydr_ a wnaeth yn ddarnau.

7 1716 T. Evans: DPO 35, Cans _brwydr_ y

Rhufeiniaid a aethai i Si@^r Fo@^n.

7 1740 id. 336, _Brwydrau_ lawer o Filwyr arfog.

Dr. G. R. Isaac of The University of Wales, Abe ystywyth, in discussing brwyd, adds that:

"The correct Latin comparison is frio 'break up', both < Indo-European *bhreiH- 'cut, graze'. These words have many cognates, e.g. Latin fr uolus 'friable, worthless', Sanskrit bhrinanti 'they damage', Old Church Slavonic britva 'ra-zor', and others. The Old British form of brwyd would have been *breitos. It is sometimes claimed that there is a possible Gaulish root cognate in brisare 'press out', but there are diffi-culties with that identification.

It may be worth stressing that the 'tryfrwyd' which means 'very speckled' and the 'tryfrwyd' which means 'piercing, pierced' are the same word, and that the latter is the historically pri mary meaning. The meaning 'very speckled' comes through 'bloodstained' from 'pierced' ('bloodstained' because 'pierced' in battle). But I do not think this has any bearing on the argu-ments.

Actually, Tryfrwyd MAY mean 'very speckled', but that is conjecture, not certain knowledge. Plausible conjecture, yes, but no more certain for that."

That "pierced" or "broken" is to be preferred as the meaning of Tribruit is plainly demonstrated by lines 21-22 of the _Pa Gur_ poem:

Neus tuc manauid - "Manawyd(an) brought

Eis tull o trywruid - pierced ribs (or, metaphori-cally, "timbers", and hence arms of any kind,

probably spears or shields; ) from Tryfrwyd"

Tull, "pierced", here obviously refers to Tribruit as "through-pierced".

Tribruit is a Welsh substitute for the Latin word trajectus. Rivet and Smith (The Place-Names of Roman Britain, p. 178) discuss the term, saying that in some cases "it seems to indicate a ferry or ford..." The Welsh rendered 'litore' of the Tribruit description in Nennius as 'traeth', demanding a river estuary emptying into the sea. However, in Latin litore could also mean simply a river-bank.

In the case of Arthur's Tribruit, this can only be the Romano-British Trajectus on the Avon of the city of Bath. Rivet and Smith locate this provisionally at Bitton at the mouth of the Boyd tributary. The Boyd runs past Dyrham, scene of the ASC battle featuring Ceawlin which led to the capture of Bath.

So, with the Tribruit found, and knowing that Agned and Breguoin/Bregion/Bregomion lie between that battle and the one fought at Bath, can we solve the riddle of these two intervening hills?

I believe we can. But we have to go back in the ASC battle list - to the same year entry that contains Limbury or "City of the Legion."

I had remembered that prior to his later piece on Breguoin ('Arthur's Battle of Breguoin', Antiquity 23 (1949) 48—9), Jackson had argued (in 'Once Again Arthur's Battles') that the place-name might come from a tribal name based on the Welsh word breuan, 'quern.' The idea dropped out of favor when Jackson ended up preferring Brewyn/Bremenium in Northumberland for Breguoin.

So how does seeing breuan in Breguoin help us?

In the 571 ASC entry we find Aylesbury as an-other town that fell to the Gewessei. This is Aegelesburg in Old English. I would point to Quarrendon, a civil parish and a deserted medieval village on the outskirts of Aylesbury. The name means "hill where mill-tones [querns] were got". Thus if we allow for Breguoin as deriving from the Welsh word for quern, we can identify this hill with Quarrendon at Aylesbury.