The Eildon Hills

Once upon a time I tried to make a case for the Elei of the Arthurian PA GUR poem being not for the Ely River in Glamorgan, Wales, but for a site in the Scottish Lowlands. My focus was on the Catrail dyke, which ran close to Mabonlaw, or better yet, the Eildon Hills. This thinking focused on what I perceived to be a "northern bias" in the poem. I had already done my best to identify the various sites mentioned in the PA GUR:

In brief, if I was right about the site identifications, then none of them fell farther south thatn Derbyshire or south Wales (assuming, in this last case, Elei was the Ely River).

More telling, I felt, was a repeated context in which Mabon of Elei was mentioned. I'm quoting here the first three stanzas of the poem so the reader can see what I'm referring to:

Note that Mabon son of Mellt (Mellt, 'Lightning', is proposed as the god's father here, in distinction to his mother, Modron) is mentioned as being active between mention of Tryfrwyd (the trajectus at North Queensferry just west of Edinburgh. This is close to Dalmeny, which Brittonic place-name expert Alan James thinks might be another Manau name. If it is, then Tryfrwyd is at the border between Gododdin proper and Manau Gododdin.

The "Lightning" father of Mabon is probably a reference to Apollo's father, Jupiter Fulgor or Jupiter of the Lightning, as Maponus was commonly identified with Apollo. Evidence for Apollo ain Roman Britain is fairly ample. There is an inscription to the god at Trimontium.

Llwch Llaw-wynnog is, of course, the god of that name, and while there is some recent scholarly opinion that disagrees, it is fairly certain that Llwch (Lugh/Lleu) has left his name in Lothian, British *Lugudūniānā (Lleuddiniawn in Modern Welsh spelling), meaning "country of the fort of Lugus".

Manawydan has been associated with Manau.

The implication seems to be, therefore, that Mabon is in the North (unless we are to assume there are TWO Mabons, one here and one south on the Ely). Alan James (in his https://spns.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Alan_James_Brittonic_Language_in_the_Old_North_BLITON_Volume_II_Dictionary_2019_Edition.pdf) notes a Drumaben in West Calder.

Some of my past blog posts that deal with a hypothetical Elei in the North are these:

I went ahead and included there my idea for the Uther Pen[dragon] who fought with Gwythur in the 'Marwnat Vthyr Pen' being the Penn son of Nethawc who fought with Gwythyr in 'Culhwch ac Olwen.' There are some Nectans attested in the region of the Eildons in the right time period. One of them can be associated with a Nudd, the same name as the father of Gwyn, opponent of Gwythyr. While the action of the 'Culhwch ac Olwen' story of Gwythyr and Gwyn takes place in Pictland, it would have been an easy matter for a Nectan in the Lowlands to have been identified with a Nectan in the Highlands through the usual folkloristic processes.

Now that I have finally committed myself to an Arthur in the North

(https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2024/05/illtud-as-arthurs-father-no-go.html), it seems necessary to explore the possibility of a origin point in the Scottish Lowlands one last time. While putting Uther and Arthur at the Banna Roman fort on Hadrian's Wall has a lot going for it, we cannot utilize any known genealogical trace or personal-names embedded in the landscape at Banna to prove their presence there. Lacking such a strand of tradition will always leave the site tantalizing, but doubtful.

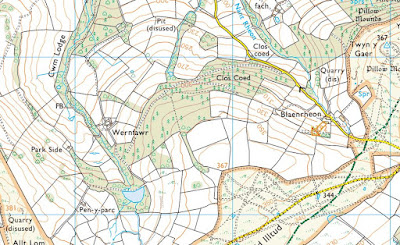

I've pasted below a map of the Catrail, showing the locations of the Eildon Hills and the Yarrow Stone in relation to the course of the dyke.

Mabonlaw is (as the crow flies) about 20 kilometers/12.5 miles from the Eildons, just to help provide scale of distance. But it is only a handful of miles from the Catrail.

Alan James has told me the following about W. mehyn:

"GPC compares mehyn with OIr magen 'lle'; that's a clue to its etymology, *mag-īno-, so related to maes. DIL s.v. maigen gives the meaning 'a piece of open land; a spot, place in the widest sense', very similar to maes. I suppose *Y Mehyn might have been used as a name for a region or district of open country."

Lle is:

"locality, area, region, neighbourhood (sometimes transf. of its inhabitants); a specific place, a general designation (e.g. for a city, town, village, farm); residence, dwelling; building or open space used for a specific purpose (e.g. worship, business, swimming)"

Given the location of Mabonlaw in relation to the Catrail, I think a sense of Palisaded Region for Eil Mehyn is quite reasonable. Despite its fairy population, we cannot attest Maponus at the Eildons. Apollo at Newstead in the Roman period, sure. But Mabonlaw can only be associated with the Catrail, not the Eildons.

Alan James, in continuing his discussion of mehyn, said -

"If you're looking for a region of open country, as mehyn might imply, in the Borders, I'd think the lower Tweed basin, downstream from Melrose to the Merse, would be likeliest. But the Catrail might possibly mark the western boundary."

Strength for the idea that Elei of Mabon may be in the North is found in my recent identification of one of the three raptors of Elei actually belonging to Preseli in Dyfed. I had wondered if the unknown -eli Preseli, given a pyrs(g) first element, 'scrub, brush', might be the same word that Professor Peter Schrijver has traced to the Ely River - viz. a word that means fence or palisade, exactly as we find in the Catrail place-name and perhaps at the Eildons. While writing this article, I heard back from Schrijver and will attach the full discussion here. His responses are in bold-face type.

"Peter, could the -eli of Preseli be akin to W. ail, Irish aile, fence, palisade? For something like brush-palisade mountain?"

"Not bad. If ‘palisade’ is indeed from *alese/a-, as I suggested, then -eli is what we would expect."

"I was thinking about your River Ely theory...

What gave me the idea is this:

In the PA GUR, one of the raptors (?) of Elei is Yscawen (or Kysceint, maybe Kysteint) son of Panon/Banon. In CULHWCH AND OLWEN, this character dies fighting the great boar at Cwmcerwyn in Preseli. Just before that some other of Arthur's men had died at the Nyfer. As it happens, the Afon Banon (later spelled Bannon) empties into the Nyfer. It seemed to me this was fairly typical use of a river-goddess place-name. That Elei was used (thought to be the Ely River in Glamorgan in this context) suggests there may have been a confusion and the son of Banon actually belongs at Preseli precisely because the second element of the mountain name is present in the river-name.

Make sense?"

"Makes sense."

I once wrote about Annan Street, so-called:

"According to https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/108609.pdf :

"The name 'Annan Street' in the Yarrow valley, which is also accompanied by a road-side cemetery, may indicate the presence of another lateral route, paralleling those in the valleys of Tweed and Lyne, and to the south over Craik Moor to Raeburnfoot, connecting Trimontium to the head of the Annan."

The Annan was the cult center of the god Maponus. Mabonlaw lies between the Annan and the Eildons.

A hero like the son of Banon who dies in Preseli could easily have been brought into the orbit of other heroes precisely because -eli of that place-name was the same as an ail- name in the North. On the other hand, Preseli was in the kingdom of the Irish-founded dynasty of the Deissi, among whom was one Arthur son of Pedr. There is no reason, though, to place Mabon in Dyfed.

Over the next few days or weeks, I will be reconsidering the possibility that Uther belongs near the Eildons - specifically, in the area of Selkirk down the Yarrow Valley from the Yarrow Stone.

NOTE: The name Artorius may be attested at Roman Trimontium: