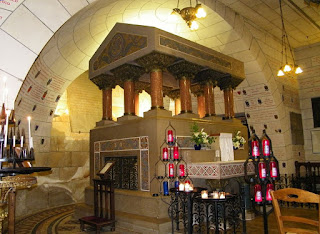

Pictish Stone at Abernethy

In the 'Elegy of Uther Pen [Dragon]', the following line occurs:

Line 11

Neur ordyfneis-i waet am Wythur,

I was used to blood[shed] around Gwythur,

In her commentary to the critical edition of the poem, Marged Haycock says:

"am Wythur On the personal name Gwythur, see §15.31. Am ‘for, around’,

perhaps here meaning that the speaker [i,e, Uther Pen] was in Gwythur’s entourage."

Why is this significant? Because in the MABINOGION tale 'Culhwch and Olwen', one of the earliest Arthurian stories, we are told that among Gwythyr's retinue is one PENN SON OF NETHAWC.

Bromwich and Thompson have the following discussion on the name Penn (in the English edition of CO, published in 1992; information courtesy Will Parker via personal correspondence):

"Penn uab Nethawc: some element appears here to be lacking. Pen(n) is itself an unlikely personal name. Nethawc could be read as Neithon, the name which developed in Brythonic as Nwython, corresponding to Nechton, Nechtan in Irish and Pictish. If so, it would be a doublet of Nwython, which follows immediately in the text."

While these authors go on to say that "Pen(n) in that case would be a possible corruption of Run, corresponding to Run mab Nywthon," given the testimony of the MARWNAT VTHYR PEN it would be more reasonable to suggest that Penn is a shortened form of Uther Penn. I think it unlikely that Run could have become Penn, in any case (see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2019/06/is-penn-son-of-nethawc-merely.html).

MABINOGION translator Gwyn Jones chooses instead to connect the previous /o/ in C&O to penn, yielding an otherwise unknown name Oben. This is unwarranted, as adequately demonstrated by Dr. Marieke Meelen in https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/40632/05.pdf?sequence=8 (p. 149-50). Dr. Simon Rodway of The University of Wales concurs with Meelen's assessment of the phrase.

Neithawc or Nethoc is an attested hypocoristic form of Neithon. For the saint Mo-Nethoc in NE Scotland, for example, see https://www.jstor.org/stable/24371933?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3A690abfbd90b60bdc989f34e698db64c0&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents, https://saintsplaces.gla.ac.uk/place.php?id=1350166381 and https://books.google.com/books?id=N9eqBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA108&lpg=PA108&dq=%22Nethoc%22%2B%22welsh%22&source=bl&ots=Z5kUOf5oT-&sig=ACfU3U2VRrLmv9KawBuNTM7CK_Ef_pbDTg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjj5LqMr7_iAhWJIDQIHSUiBr8Q6AEwCHoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=%22Nethoc%22%2B%22welsh%22&f=false.

The fascinating thing about the possibility that Uther Pen's father was named Nechton is the presence of a saint of this name at Hartland Point near Tintagel. The same saint is also to be found at Tintagel itself, although this is believed by some to be a modern false attribution (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Nectan%27s_Kieve and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Nectan%27s_Glen). Hagiographer Professor Nicholas Orme disagrees (personal communication). In any case, I had long ago theorized that either Hartland or Tintagel was the Promontory of Herakles of Ptolemy, and that Eigr (from a Celtic word akin to the root of Greek akron, 'headland') was either a personification of the Tintagel promontory or even a reflection of Hera Akraia. Arthur fights 12 battles, similar to the 12 Labors of Hercules, and his birth story matches that of Hercules.

Could it be that Arthur was relocated from the North to Tintagel hard by Hartland at least in part because there was a Nechtan at these latter places?

The pedigree attached to Arthur by Geoffrey of Monmouth has long been known to be fraudulent. Yet no earlier, more genuine genealogy has been forthcoming. Might we propose that at some point in the pre-Galfridian legend Arthur's grandfather bore the name Nechtan?

And if he did, what would this mean for our Northern Arthur?

There is good reason for believing that the Nwython of C&O is the 5th century Pictish king Nechtan Morbet. His son Cyledyr is, rather transparently, a made-up name derived from the Latinized Irish name for Kildare.

From https://anthonyadolph.co.uk/the-pictish-king-list/:

Necton morbet filius Erip xxiiij. regnavit Tertio anno regni ejus Darlugdach abbatissa Cilledara de Hibernia exulat pro Christo ad Britanniam. Secundo anno adventus sui immolavit Nectonius Aburnethige Deo et Sancte Brigide presente Dairlugdach que cantavit alleluia super istam hostiam. [Necton gave land for the building of a church at Abernethy dedicated to St. Brigid of Kildare.]

Optulit igitur Nectonius magnus filius Wirp, rex omnium provinciarum Pictorum, Apurnethige Sancte Brigide, usque ad diem judicii, cum suis finibus, que posite sunt a lapide in Apurfeirt usque ad lapidem juxta Ceirfuill, id est, Lethfoss, et inde in altum usque ad Athan. Causa autem oblationia hec est Nectonius in vita julie manens fratre suo Drusto expulsante se usque ad Hiberniam Brigidam sanctam petivit ut postulasset Deum pro se. Orans autem pro illo dixit: Si pervenies ad patriam tuam Bominus miserebitur tui: reg-num Pictorum in pace possidebis.

Unfortunately, a connection between Arthur and the 5th century Nechtan is highly unlikely, and for many reasons. But one important point should be made: Nechtan is the Celtic cognate of the Latin sea god Neptune. A divine Nechtan who is associated with water is found in Irish mythology. As I've mentioned before, the story of Arthur's birth not only is paralleled by that of Hercules, but by that of Mongan, who is sired by Manannan son of Lir, 'son of Sea.'

As always, there is nothing certain in any of this. Uther Pen of the elegy poem may have been fancifully associated with the Penn son of Nethawc of C&O. Or the Galfridian tradition placing Uther at Tintagel near a known St. Nechtan location may have contaminated C&O, despite the fact that Penn son of Nethawc is firmly placed in the North in this last source. Not only are we told the battle between Gwyn son of Nudd and Gwythyr takes place in the North, Nethawc/Nwython is beyond doubt Pictish, and Gwrgwst Ledlwm and his son Dyfnarth (= Fergus Mor and Domangart) are Dalriadan.

It is possible that this Penn, 'Chief, Head', son of the Pictish Nethoc or Necton is a Welsh import of Cind, father of Cruithne (Cruithne being the eponymous founder of the Picts). There was also a Brude Cind. See https://anthonyadolph.co.uk/the-pictish-king-list/. Or the name may have been borrowed from that of Baetan mac Cinn, King of the Cruthin, mentioned in the Annals of Ulster at year entry 563. If I'm right, then any connection between Uther Pen and the Penn of C&O is a purely fictional one.

Cind/Cinn is the Q-Celtic equivalent of Welsh Pen[n].

HOWEVER, THERE WAS ANOTHER NEITHON OF THE NORTH, AND I WILL EXAMINE HIM MORE CLOSELY IN A FUTURE BLOG POST.

Update 6/1/2019: https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2019/06/uther-pen-son-of-nethawcnwython-part-two.html

https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2019/06/is-penn-son-of-nethawc-merely.html