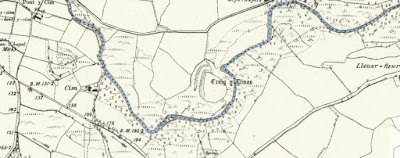

CRAIG-Y-DINAS CAMP NEAR PENYGROES, GWYNEDD

Sometimes I get questions from readers I don't really want to hear. Over the last few weeks I was dealing with what appears to be a fairly strong identification of Tintagel/Dundadgel in Cornwall as a relocation of Caer Dathal in Gwynedd. Eventually, I decided to dispense with this as yet another instance of spurious tradition. However, it remains true that the only birthplace we know of for the Arthur of the HISTORIA BRITTONUM and the ANNALES CAMBRIAE is Geoffrey of Monmouth's Tintagel. And if, as seems to be the case, this last is actually a substitution for Caer Dathal, then ought we not to pay more attention to the Arfon fort?

There is no doubt that Caer Dathal was once a very important site. I have identified it as the place where the Irish king Tuathal Techtmar stayed during the Roman period (see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2019/01/caer-dathal-and-its-ancient-ruler.html). But even had I not linked it with Tuathal, the MATH SON OF MATHONWY reference to Gwydion walking from the fortress to the sea and then past Dinas Dinlle and Caer Arianrhod towards Abermenai would have left us no other possible candidate, geographically speaking.

The local form of Tintagel - Dundadgel - is something I have only found in Ekwall and in a couple of other old sources (see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2020/05/caer-dathal-and-dundadgel-tintagel.html). To confirm that such a spelling (or pronunciation?) did occur, I have sent queries to the Cornish Archives and Studies Library. I will share anything they find here, of course. For now I can only say this: Patrick Sims-Williams (in his IRISH INFLUENCE ON MEDIEVAL WELSH LITERATURE) discusses 'phonetic confusion of d and t and scribal confusion of c and t.' Then there is the standard Welsh c to g mutation. If spellings and/or pronunctiations of -tagel were similar enough to Dathal, and I am right about Eliwlad grandson of Uther and Madog son of Uther both belonging at Nantlle just east of Caer Dathal on the Afon Llyfni, and CULHWCH AND OLWEN is correct in claiming the Uther was related to the men of the Arfon fort, then we must allow for the strong possibility that Arthur's origin is to be found at Craig-Y-Dinas Camp.

In a previous blog piece (https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2020/04/madog-son-of-uther-brief-study.html), I did mention that Emyr Llydaw, the 'Emperor of Brittany', had a son named Madog. As it happens, in terms of the estimated chronology of generations for this personage, he is better suited as Arthur's father than Sawyl of Ribchester (see Bartram's entry on Emyr). The Welsh identified him with Geoffrey of Monmouth's Budicius, but this may not be correct. For Llydaw is a name of a lake from which flows the river that runs past Dinas Emrys in Eryri/Arfon. This could well be the Llydaw of Uther Pendragon.

In other recent posts, I have argued that Dinas Emrys may have been sacred to Mabon son of Modron (Cyricus and his mother Julitta being the Christian replacements; see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2020/05/was-dinas-emrys-fort-of-mabonmaponus.html and https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2020/05/st-curig-at-dinas-emrys-proof-positive.html), and both that god and Lleu are associated with Nantlle. Lleu, of course, was a frequent visitor at Caer Dathal. We are told in the PA GUR poem that Mabon was the servant of Uther Pendragon.

My own feeling is that the PA GUR poem's Elei of Mabon is an error for the Elleti of Ambrosius in Nennius. Campus Elleti was at Llanilid on the Ewenny, but there was another Llanilid on the Nant Llanilid, a tributary of the Ely. The holy boy-saint Cyricus and his mother Julitta of Llanilid replaced the pagan Mabon and his mother Modron, and it may well be Mabon who appears at Dinas Emrys, masquerading as Ambrosius 'the Divine/Immortal' boy. It may be significant that Mabon of Elei is referred to in the PA GUR as the servant of Uther Pendragon.

My own feeling is that the PA GUR poem's Elei of Mabon is an error for the Elleti of Ambrosius in Nennius. Campus Elleti was at Llanilid on the Ewenny, but there was another Llanilid on the Nant Llanilid, a tributary of the Ely. The holy boy-saint Cyricus and his mother Julitta of Llanilid replaced the pagan Mabon and his mother Modron, and it may well be Mabon who appears at Dinas Emrys, masquerading as Ambrosius 'the Divine/Immortal' boy. It may be significant that Mabon of Elei is referred to in the PA GUR as the servant of Uther Pendragon.

It would seem, therefore, that there are a lot of reasons for situating Arthur and his father in this region of Wales. Can we afford to ignore the Welsh evidence, such as it is?

Well, Geoffrey's Gorlois, Duke of Cornwall at Tintagel, is a created personage. His name comes from the gorlassar epithet Uther applies to himself in the MARWNAT VTHYR PEN. If Tintagel is a relocation of Craig-Y-Dinas/Caer Dathal, then Uther belongs at the latter fort. Plain and simple. The question would then be what it has always been: who was Uther?

Cunedda was, undeniably, the "Emperor of Llydaw" in Gwynedd. The Caer Engan (Eniaun) between Craig-Y-Dinas and Nantlle may have been named for one of the Eniauns who descended from Cunedda. Cunedda's son, Ceredig/Cerdic of Wessex, is the only decent candidate for Arthur - if we are going to opt for an Arthur who comes from Wales. I once wrote an entire book on Ceredig as Arthur. Why did I remove it from publication? Because I could not pin down Uther's location, and was stuck on two things: 1) the possible presence of the name Sawyl in the Uther elegy (something I no longer maintain is a credible emendation) and 2) Uther having a son named Madog (whom I identified with Sawyl's son of that name). But I have since decided on cannwyll for the disputed word in the elegy poem, and can accept Madog as son of the Emyr Llydaw Cunedda.

Where does that leave me? Feeling compelled to once more make available THE BEAR KING: ARTHUR AND THE IRISH IN WALES AND SOUTHERN ENGLAND.

P.S. AS SOON AS I HAVE COLLECTED ALL THE DATA PERTAINING TO THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE TINTAGEL PLACE-NAME, I WILL MAKE A DECISION ON HOW TO MOVE FORWARD WITH THIS NEW/OLD ARTHURIAN THEORY.

P.P.S. Here is the most current treatment of the Tintagel place-name, as prepared by Andrew Climo of The University of Exeter:

Summary

Sources and Hypotheses

Phonology

Morpheme Splitting

P.P.S. Here is the most current treatment of the Tintagel place-name, as prepared by Andrew Climo of The University of Exeter:

Notes on the name Tintagel

Summary

Toponymists have struggled with this name

for decades and place name evidence for Tintagel is sparse. One way forward is

to go with the attested form Tintaieol as a basis, as it may preserve

the Cornish pronunciation from c.1200. Toponymists have glossed over the matter

of the <o/e> alternation, but this is adequately borne out by the

examples provided in the texts. Unfortunately, this makes Weatherhill’s highly

attractive Tente D’Agel ‘Devil’s Stronghold’ look unlikely. It is

reasonable to substitute initial <d> and assume that ‘Din’, fortress, is

the prototheme on the basis of consonance. This renders Dintajeol. One

could then leave open the matter of whether *Tajeol was a personal name,

refers to the Devil (C. ‘Dyawl’, or something different entirely. This way

forward accounts for all morphological features seen within the texts and

provides a usable form.

Sources and Hypotheses

Sources (in Padel, 1988; Weatherhill, 2005).

The following apply to Tintagel Head and/or Castle:

·

Padel: Tintagol c.1137; Tyntagel

1208

·

Weatherhill: Tintagol

c.1145

As both point out the settlement of

Tintagel was Trewarvene 1259; and Trevenna c.1870 (Padel).

Weatherhill thinks the name is Norman French Tente d’Agel ‘Devil’s

Stronhold’, cf. Tintagau (Sark).

Ekwall’s assumes a <dg> spelling, perhaps

based on the notion that Middle English <g> is [dʒ].

The spelling <dg> appears speculative although was used in Middle Cornish

from time to time although the Norman French usage of <g> was also common

and <gg> is also found. Neo-Cornish uses the graph <j> to represent

[dʒ], and native Cornish names used would have derived from either <s> or

<d> in Old Cornish.

Phonology

There is a need for additional forms to

make a clearer determination on linguistic grounds, but Layamon’s Brut (in

Project Gutenburg), which is in Middle English, shows Tintateol,

presumably a transcription error from Tintaieol, which also occurs in

that text, as well as the form Tintageol, which suggests that <g> really

was pronounced [dʒ] ~ <j>.

The initial <t> is easily explained

as a substitution for <d> ~ [d], and as pointed out by Padel (1985, p.85)

is found in names such as Tenby, Tintern. Initial fortis (hardening of d à t or g à k) is not much of a stretch,

particularly resulting from consonance (so the consonants at the front, middle

or end then agree).

If Weatherhill is correct that the name is

NF and one can assume <g> ~ <j> ~ [dʒ], then Tente d’Agel could be

rendered in Cornish as Tentajel. The alternation of spellings <e/i> is

common in C. and whether it is of any consequence or not is a question for

another day and still occupies C. users of different persuasions.

On the other hand, if Padel is correct and

it is C., then it would be spelt in MC something like Dintajel, Dintajol or

Dintajeol. Din is the m. noun ‘fortress’ so *tajel/tajol/tajeol is a qualifying

name, noun or adjective, presumably in MC. However, the suggestion that *tajel

< *tagell ‘neck’, ‘noose’ or ‘constriction’ is problematic: Whilst it makes

topographically tempting, it would require a NF qualifying noun added to a C.

prototheme and then a series of changes to occur to provide the present

spelling (Din > Din-tagell > Dintajeol > Tintagel). This seems a bit

of a stretch. The other issue is that there is a vowel alternation <o/e>

or possibly <eo>, which should not be casually dismissed (neither Padel

nor Weatherhill address this).

Morpheme Splitting

There are several ways that tajeol might be

split: (i) ta-, (ii) taj- or (iii) taje-. The first way of splitting might

suggest the preposition -to or -de ‘unto’, which typically

requires a personal name following. ‘Devil’ was diavol (Voc. Cor.), so the

hypothesis of ‘Devil’s Fortress’ could conceivably work with a little forcing:

*Dintodiavol > *Dintodyawl > *Dintojawl. Second and third way of

splitting would suggest an OC root *tadi- or *tado-, and potentially an

instrumental suffix -illo: *tadoel > *tajeol. As a parallel, one thinks of

the name *teuto-uualos ‘Warrior of the People’ > *Tudwal.