ARTHUR DUX BELLORUM AND CEIDIO SON OF ARTHWYS

There has always been a problem with the ‘dux bellorum’ title applied to the legendary Arthur.

To begin, there is a misconception that the socalled title actually appears this way in the text of Nennius’s Latin HISTORIA BRITTONUM. In fact, it does not. The text actually reads ‘sed ipse dux erat bellorum’, ‘but he himself was leader of battles’. As has been discussed before by experts in early Medieval Latin who have studied Nennius, this is NOT a title. It cannot be equated, therefore, with the dux legionum rank of the third century Roman Lucius Artorius Castus, who led a single campaign against the Armenians. It certainly can’t be compared with the same man’s rank of praefectus (castrorum) of the Sixth Legion at York. For a good discussion of the ranks held by LAC, see http://christophergwinn.com/arthuriana/lac-sourcebook/.

This description applied to Arthur in the HB seems to have led to him being referred to in subsequent sources as simply a miles or ‘soldier.’ The idea has often been floated that this means Arthur was not a king and, in fact, may not even have been of royal blood. Truth is, Arthur may not have been king – if he predeceased his father, for instance. We do not have to resort to the 2nd-3rd century Roman soldier Lucius Artorius Castus to account for the 5th-6th century chieftain being considered only a ‘leader of battles.’

But if not a title, could this Latin phrase have designated a secondary, purely British name belonging to Arthur?

Myself and others have pointed out that attested early names such as Cadwaladr, (“Catu-walatros) ‘Battle-leader’, Caderyn (Catu-tigernos), ‘Battle-lord’, Cadfael (Catu-maglos), ‘Battle-prince’, Caturix (a Gaulish god), ‘Battle-king’, could have yielded a description such as ‘dux erat bellorum’. No names of this nature appear to have been known in the North (where I’ve shown Arthur to belong) during the Arthurian period.

However, it has recently occurred to me that my tentative genealogical trace of Arthur to Arthwys, the latter being a name or a regional designation of the valley of the River Irthing on the western part of Hadrian’s Wall, may hold the clue to unraveling the dux bellorum mystery. Arthur died at Camboglanna/Castlesteads on the Cambeck, a tributary of the Irthing.

The son of Arthwys in the genealogies is given as Ceidio, born c. 490 (according to P.C. Bartram), quite possibly the same chieftain whose son is mentioned in the ancient Gododdin poem as ‘mab Keidyaw’. John Koch and others have discussed Ceidio as a by-form of a longer two element name beginning with *Catu-/Cad-, ‘Battle’.

Dr. Simon Rodway was kind enough to write the following to me on Ceidio:

“Ceidiaw is a 'pet' form of a name in *katu- 'ba tle' with the common hypocoristic ending -iaw (> Mod. Welsh -(i)o) found in Teilo (Old Welsh Teliau) etc., and still productive today (Jaco, Ianto etc.). And yes, it's not possible to say what the second element would have been. But the forms you suggest [Cadwaladr, Cateryn] are among the candidates, especially as this man was a chieftain of Y Gogledd [the North] at the head of some of the royal genealogies. ”

In other words, this Ceidio would originally have had a full-name of the type Cadwaladr or Cateryrn. Unfortunately, we can never know what the second “dropped” element of his name might originally have been. However, if Roman naming practices had been preserved in the North during Arthur’s time, we would reasonably expect a form such as X Artorius Z, where X, the praenomen, was the given name, Artorius was the nomen, i.e. gens or clan name, and Z was the cognomen, i.e. the name of the family line within the gens. A Cad- name, shortened to Ceidio, might well have been one of Arthur’s other names.

Of course, by the time of the 5th-6th centuries, the Roman gens name Artorius may well have been given to a prince as his praenomen. If the name had retained its status as a gens name, then that would mean someone in the Irthing River region actually traced his descent from Lucius Artorius Castus. While this could be either a genuine or fabricated trace, it is also possible the name was remembered as belonging to a famous figure of legend and passed on to a favorite son for that reason alone.

In the contents description of the Harleian recension of Nennius, we find the phrase ‘Arturo rege belligero’, something usually translated as “King Arthur the warrior”. More accurately, this is ‘Arthur the warlike or martial king’. Suppose we allow for rege belligero as an attempt at a literal Latin rendering of something like Cadwaladr or Cateryn?

The fifth century St. Patrick, who I’ve shown came from the Banna fort on Hadrian’s Wall at modern Birdoswald on the Irthing, is known to have had a typical Roman style ‘three-part’ name: Patricius Magonus Sucatus. Patricius is believed to have been his Christian name, assumed after his conversion, but it is just as possible he bore a classic Roman-structured name from birth. In any event, Patricius is decidely Latin, while Magonus and Sucatus are British names.

If I’m right about Arthur being a son of Arthwys – or being FROM Arthwys – and we can allow for Ceidio son of Arthwys having originally born a name like Cadwaladr or Cateryn, then it is not inconceivable that Arthur DOES appear in the Northern genealogies after all.

Arthur and Ceidio would be one and the same man.

CEIDIO SON OF ARTHWYS AND POWCADY, CUMBRIA?

According to the early Welsh genealogies, Gwenddolau ('white dales'), who belonged at Carwinley in Cumbria, was the son of Ceidio. Ceidio as a name is a hypocoristic form of a longer two-part name that begins with *cad-, 'battle.'

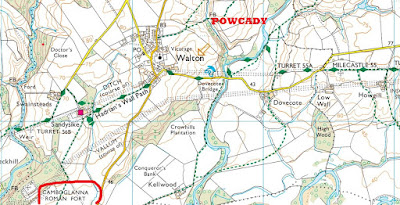

Recently, I thought to look for a relic of Ceidio in place-names. As he was a son of the Arthwys who stands for the *Artenses or People of the Bear of the Irthing Valley, my attention was caught at first by Powcady between the King Water and the Cambeck not far from the Camboglanna Roman fort at Castlesteads. Early forms for Powcady were late: Pocadie, Pokeadam. But Alan James proposed that this contained a typical pol- element 'pool in a stream, stream' plus cad-, 'battle', plus perhaps a -ou plural suffix. I wondered if it could instead contain the name Ceidio/Keidyaw/Ceidiaw.

Powcady is at a footbridge over Peglands Beck, which was earlier known as Polterkened. See

As Polterkened (or at least Kened, as polter may have been added later) was this stream's ancient name, a *pol- of a different name on the same watercourse would designate a pool in this location. I asked Alan James whether this could be 'Ceidio's Pool.' He responded:

"Poll Ceidio isn't impossible, though it should be lenited *Geidio (but lenition is a bit iffy in Cumbric pns). So, no, not impossible."

I would very tentatively propose, therefore, that the name Ceidio son of Arthwys/Artenses is preserved at Powcady.

.jpg)