Pages from the Bosworth and Toller Anglo-Saxon Dictionary

Several months ago I made what I thought to be a huge discovery. Although I had succeeded in gathering a large amount of information that seemed to support the notion that Ceredig son of Cunedda/Cerdic of Wessex was the Arthur, I had failed yet again to definitively demonstrate that Cunedda/Ceawlin should be identified as Uther Pendragon.

This shortcoming was removed when I realized that the Pen Kawell of 'Chief/Chieftain Basket' of the MARWNAT VTHYR PEN elegy could be related to the Ceawl- of Ceawlin, as in Anglo-Saxon ceawl not only meant 'basket', but was derived from the same Medieval Latin cavellum as the Welsh cawell.

This finding, I felt, was nothing short of remarkable, and provided me with the Holy Grail of Arthurian Studies - a historical personage of significance with whom to link the famous Arthur. A personage who stood outside the fictional orbit into which Uther had been bound by Geoffrey of Monmouth.

But my delight and excitement was rather short-lived, despite my producing a book on the subject. Why?

holly *kolinno- (?), SEMANTIC CLASS: plant, Gaulish *Colini-ācus ‘holly-place’, Early Irish cuilenn ‘holly’, Scottish Gaelic cuilionn ‘holly’, Welsh celyn ‘holly’, Cornish kelin (Old Cornish) ‘gl. ulcia ‘holly’, Breton colaenn (Old Breton), quelennenn (Middle Breton), kelen(n) ‘holly’

I worked diligently with Dr. Richard Coates on the problem, but he was not encouraging. Coates had written an article discussing the name Ceawlin

"Derivation as a nickname-form from Old English ceawl 'basket' seems implausible, and *Ceawl certainly never occurs as a theme in dithematic names (it is scarely semantically appropriate)."

His own etymology, put forward with extreme caution, was as follows:

When I asked him if Ceawlin could derive from Cuilenn, his answer was brief and devastating:

"Phonologically, OE /aw/ or /a:w/ doesn’t look good for OIr /u/."

At the time, I did ask him about Bede's form for Ceawlin, i.e. Cælin. Dorothy Whitelock (THE ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE: A REVISED TRANSLATION, p. 4, note 6) reminds us that

"[Mss.] 'A' and B have Celm, a misreading of Celin, an Anglian form of the name Ceawlin. Sw. has Ceaulin."

Suppose Irish Colin/Cuilin had come through the Welsh as Celyn (the cognate form). And this was related to AS cel, 'basket', for which ceawl was later substituted. Could this have happened?

"Not really. Cel seems to me to be just an unusual spelling for ceawl. Under all normal assumptions, pre-8thC Britt. *colin- >> OE *colin or, any other form would be due to analogy of some description. Analogy would just mean that the Britt. name would have been taken into OE in a form influenced by the receiver’s knowledge of the OE word, in this case ‘basket’, however it was spelt. In other words, any OE form which is not Colin or Celin would need to be explained by speakers connecting it with some other word or name and changing the form of the borrowed name accordingly. I am not a great believer in using arguments of that type to explain unexpected name-forms, as you may have realized by now, though I accept that it may happen occasionally."

Dr. Alaric Hall of Leeds was most helpful in helping me to come to grips with the /ea/-/ae/ difference in Ceawlin and Caelin, as well as the apparent loss of the /w/. Here is what he passed along:

"The c- dipthongised subsequent front vowels regularly in West Saxon, but irregularly in Northumbrian. So Bede's form Caelin (probably in Bede's time pronounced /'kjæ:lin/, later /'ʧæ:lin/) looks like a conservative, Northumbrian form, with no palatal diphthongisation, whereas the form Ceawlin looks like it's undergone palatal diphthongisation, turning the monophthong æ to the diphthong spelled ea but usually thought to have been pronounced /æɑ/.

By the time Ceawlin lived, it's plausible that palatal diphthongisation had happened in West Saxon, in which case the different West Saxon and Northumbrian pronunciations both existed in his lifetime--and Ceawlin himself presumably spoke in a West Saxon accent. But the Northumbrian spelling of the vowel represents, in this respect, a more conservative variety of Old English.

I don't have an easy answer about the -w-: it doesn't help that we aren't sure about the etymology of the name! I note that -w- often gets lost word-finally in West Germanic (but that it diphongises vowels when it is lost, which we don't see in Cælin; Campbell §120.3) before consonants when it's begins the second element of a compound noun (Campbell §468), which isn't precisely what's going on here, but might provide a parallel for the loss of -w-.

I was bothered/intrigued enough by this problem that I've created a Wikipedia entry for the name:

Still no solutions from me though!"

Dr. Coates had a different idea for the dropping of the /w/ in Ceawlin:

"I suppose explicable in terms of a reminiscence of Latin words in cael- and in the absence of <-wl-> in Latin orthography."

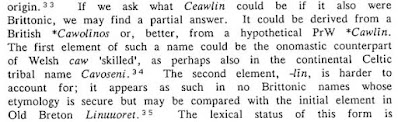

Under his Wiki article on the name Ceawlin, Prof. Hall mentions John Insley's derivation for the name, which approaches it from the Anglo-Saxon and not the Celtic. The relevant source is John Insley, 'Britons and Anglo-Saxons', in Kulturelle Integration und Personennamen im Mittelalter, ed. by Wolfgang Haubrichs, Christa Jochum-Godglück (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2019), and I have here excerpted the section on Cealwin:

Yet another idea was put to rest when I passed along a comment from an older book on the possiiblity of confusing /ui/ and /iu/ in MSS.:

"The variations of such names, from the similarity of m, in, ni, ui, and iu, in early MSS. [of Wace, Geoffrey, ASC] are innumerable."

That would require that a corrupt spelling resulting from a single transpositional copying error came to determine the canonical form of Ceawlin. Not considered at all likely - by anyone - and thus quickly dismissed.

The very last weapon in my arsenal was what is known in Welsh linguistics as diphthongization. In some cases, and at different times in the development of Welsh, o could become au (aw) or au could become o. The process is nicely explained in

Unfortunately, Dr. Simon Rodway was quick to burst my bubble when it came to this possibility:

"The /o/ in COLINE is short, and short /o/ never under any circumstance becomes /au/."

And that is where things were left.

But then I had an epiphany of sorts. I recalled writing this piece:

In it, I had cited the opinion of top Anglo-Saxon scholar Barbara Yorke (an opinion echoed by others in her field). She expressed the very real possibility (I would say probability) that Cerdic and Cynric had originally been British chieftains who had been co-opted by the English historians by being made founders of Wessex.

Remembering this, I asked myself a straight-forward, simple question: if an English historian had intentionally set about to consciously create such a fraudulent tradition in order to glorify his own

race, might he not choose to disguise a Celtic Coline/Cuilin (or even a Celyn) by simply altering it to Ceawlin? Might this process have been abetted by the occasional use of cel for ceawl?

This would be a matter of ethnic propaganda, not one of folk etymology or strict linguistic development. We need not even allow for what Coates describes as an extreme and undesirable rarity in philology.

As Ceawlin was the greatest of the Gewissei, and a Bretwalda to boot, making him into someone thoroughly English by merely substituting Ceawl- for Col-/Cuil- would be an exceedingly wise move on the part of our English chronicler.

THIS PROCESS WOULD ALSO EXPLAIN WHY THE NAME CEAWLIN CAN'T BE PROPERLY ETYMOLOGIZED.

The Welsh had done much the same thing when they converted Cuinedha Mac Cuilinn of Drumanagh in Ireland directly across from Gwynedd to Cunedda Maquicoline son of Edern (Eternus) of Manau Gododdin in the far North of Britain. There is ample evidence in the Welsh genealogical tracts - when these are compared to their Irish counterparts and related to known areas of Irish settlement in Wales - to demonstrate conclusively the Welsh wished to hide their Irish ancestry and substitute for it one based on purely British predecessors who had descended from Imperial Rome. The best example of what I'm talking about concerns the Deisi Irish-founded kingdom of Dyfed. There is even good reason for believing that Vortigern was half-Irish (

http://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/07/appendix-ii-vortigern.html) and the only other men of this name are the several Fortcherns found in early sources. On the famous Eliseg Pillar in northern Wales, Vortigern is said to have married a daughter of Magnus Maximus. Other Welsh royal pedigrees go back to progenitors with Roman names and/or Roman emperors (

https://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/genealogies.html).

So why not the English altering Irish Colin/Cuilin to Ceawlin and claiming him as English?

As I always do, I went right back to the authority who had recently shot me down. There was no one more qualified than him to soberly and objectively address my last line of defense in the proposed Colin/Cuilen/Celyn/Cælin = Ceawlin identification. Because this was so, I did not feel it would be intellectually honest to publish anything that did not have at the very least his qualified approval. Critical acumen matters.

His reply?

"Well, I don’t know any parallels, which makes the question more difficult than it looks. Yes, it’s theoretically possible."

While this is not exactly a ringing endorsement of my idea, Dr. Hall was quite a bit more encouraging:

While this is not exactly a ringing endorsement of my idea, Dr. Hall was quite a bit more encour-aging:

“Trying to get from either Colin or Celyn to Cælin/Ceawlin is that the lowering of the e or o to æ~ea would be very odd in this context (if an-ything you'd expect the -i- in the second syllable to raise rather than lower the preceding vowel), and I haven't found any evidence for such a sound change.

But your idea that the oddness of Ceawlin is just caused by the orthographic mangling of an un-familiar name by a scribe or series of scribes strikes me as reasonable; the idea that analogy with the word ceawl might have encouraged this isn't mad, even though the Dictionary of Old English doesn't seem to attest to cel~cawl varia-tion. (I created a Wiktionary entry for OE cawl, by the way: https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/cawl#Old_English). You could compare the putative mangling of Ceawlin to the fate suffered by other, definitely Brittonic names in the ASC entry for 577; Pat-rick Sims-Williams touches on this in 'The Set-tlement of England in Bede and the Chronicle', Anglo-Saxon England, 12 (1983), 1--41. I doubt we'd be dealing with a deliberate attempt to dis-guise a Brittonic name as an Old English one, but the possibility that scribes were just getting into a bit of a mess is entirely plausible.”

“Coinmail, if we regard the first I as intrusive (some texts lack it), is Welsh Cynfael (OW Conmail). Condidan is probably Welsh Cynddylan (OW *Condilan), with oral or scribal assimilation of d-l to d-d. Farinmail is presumably the same as southern Welsh Ffernfael, Ffyrnfael (OW Fernmail). It is often claimed that the spelling of the names shows that the Chronicler was following very early, perhaps even contemporary sources. This is not so. The only one which suggests a date earlier than the ninth century is Farinmail, which appears not to show the seventh-century i- affection that would turn Farin- into *Ferin-, whence *fern- by an unusual late syncope. But to take Farinmail at face value like this would more or less commit us to an etymology *Farinomaglos ‘meal-prince’, a rather amazing Latin-Celtic hybrid with semantics like OE blaford. It may be safer to regard the first i of Farinmail as a scribal error in a series of minims, like that of Coinmail, and to treat *Farnmail as a bad spelling of Fernmail."

What does this mean for the Arthurian theory I present in my book THE BEAR KING?

Well, I must once again prefer it over the Northern Theory, which I presented in full in a separate volume (

https://www.amazon.com.mx/Battle-Leader-North-Definitive-Identification-Legendary-ebook/dp/B0B5CG54RT). The problem with the Northern Theory

was the absence of a genealogical trace for Arthur's father, Uther. I was forced to accept this grave limitation as part of the premise for the new volume. Yes, there was a tempting though frighteningly tenuous connection with the Penn son of Nethawc of CULHWCH AC OLWEN (as that personage fought for a certain Gwythyr, and a Gwythur appears in the MARWNAT VTHYR PEN), but that particular Penn was almost certainly one of the Pictish Cinds, and there was no direct path in the extent Welsh tradition that would allow us to identify Uther Pendragon with a Cind. Nor would it make any sense to place Arthur in Pictland!

On the other hand, the Welsh insisted that Uther was related to the men of Caer Dathal in Arfon, and I had proved that Caer Dathal was not only Dinas Emrys, but that Geoffrey of Monmouth had substituted the Cornish Tintagel for the Welsh hillfort. A strong attachment to Gwynedd served to support my arguments in favor of Uther as Cunedda, father of Ceredig/Cerdic of the Gewissei.

While the Arthur/Artorius name may well have been preserved in the North (I pointed to Dalmatian-derived Roman military units at York and Carvoran on Hadrian's Wall as possible origin points for such a name), it was also true that a unit from Segontium/Caernarvon near Dinas Emrys was sent to serve in Dalmatia. Some of the men from this unit might have retired from service and returned home, bringing knowledge of the great L. Artorius Castus's career in Britain and Armenia with them. There is good reason for thinking the double serpent insignia of the Segontium unit was one of the elements that went into the story of the dragons on Dinas Emrys/Caer Dathal.

Our conclusion must be, therefore, that once we reject the bogus pedigree supplied by Geoffrey of Monmouth, the only other family relationship we can establish for Arthur belongs to the descendents of Cunedda. We have no such tie for an Arthur of North Britain.

It is for this reason that I will soon be re-offering THE BEAR KING for sale through Amazon. The book will include a section detailing what I covered in this blog post.

I thank my readers for "bearing" with me this long (pun strictly intended). This kind of research demands a great deal of flexibility, concession and compromise. One has to be willing to be wrong over and over again, and to accept the fact that others may see in this progression/regression of putative knowledge only a pronounced degree of indecisiveness, brought about by uncertainty. Sure, I have been accused of constantly changing my mind, of being "wishy-washy." What my condemners don't understand is that anyone who adheres stubbornly to this or that theory despite evidence or good argument to the contrary (something always due to ego-investment in one's own preconceived belief or concern for public reputation) is pretty much always doomed to being wrong.

.JPG)