NOTE: Since writing this piece, I have had time to consider whether I think it reasonable that Agned would merely be a W. rendering of L. Agnetis. To be honest, I now think this unlikely. And, in fact, looking at Agned as it serves in some MSS. as a substitute for Bremenium/High Rochester, I now believe I can offer a much better alternative origin for the place-name. Something which I will attend to in a future blog post...

RIB 1267. Altar dedicated to Minerva at Bremenium/High Rochester

I have long rested content with my identification of Arthur.s Mt. Agned battle site with that of Breguoin/Bremenium/High Rochester, Northumberland. I had made the identification thusly:

<Well, as it happens there another very exciting candidate for Agned available to us. A Roman inscription was found at Bremenium/High Rochester with the word EGNAT clearly carved upon it. The full reading of this stone is as follows (from http://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1262):

“To the Genius of our Lord and of the standards of the First Cohort of Vardulli and of the Unit of Scouts of Bremenium, styled Gordianus, Egnatius Lucilianus, emperor's propraetorian legate, (set this up) under the charge of Cassius Sabinianus, tribune.”

This Egnatius was the governor of Britannia Inferior, i.e. Northern Britain, and as such would have been based at York. He is known from another stone as well, found at Lanchester (http://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1091):

“The Emperor Caesar Marcus Antonius Gordianus Pius Felix Augustus erected from ground-level this bath-building with basilica through the agency of Egnatius Lucilianus, emperor's propraetorian legate, under the charge of Marcus Aurelius Quirinus, prefect of the First Cohort of Lingonians, styled Gordiana.”

There has been some speculation concerning this man, who may have been of very famous stock (see Inge Mennen’s “Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193-284, note 79, p. 101). In any case, as a governor and a rebuilder of forts, his name may have been become attached to that of Bremenium in a sort of nickname fashion – ‘the hill of Egnatius’ or, as it came down to us in the HB, Mount Agned. Such a nickname may have been purely a local or even legendary development. A good comparison to Bremenium as Egnatius’s hill would the Uxellodunum fort at Stanwix, called Petriana after its military garrison.

According to Dr. Simon Roday of the University of Wales,

“Agned cannot derive regularly from Egnatius, but I don't think it's impossible - as you say, there are examples of a- ~ e- in Welsh (agwyddor ~ egwyddor etc). Perhaps a sort of metathesis?”

The examples I had cited were merely a handful I had culled from some of the early Welsh poems:

engai, angai, engis, angwy, etc.

edewi, adaw, adawai, edewid

endewid, andaw

ail, eil

Doubtless more such instances of /a/ for /e/ could be found in other texts.

In answer to the criticism that the Egn- of Egnatius would have undergone a sound change to Ein- by the 9th century, Dr. Rodway added: "Old Welsh spelling was conservative in this respect, so it would be quite regular for the g to still be written.">

This seemed clever enough, but I have also felt it was a bit... strained. For I knew with absolute certainty - having consulted the best of the Celtic linguists and place-name specialists - that the most regular etymology for Agned was a Welsh form of Latin Agnetis, the genitive form for St. Agnes. Such an interpretation tied in nicely with Geoffrey of Monmouth's identification of the site with a Maiden Castle, as Agnes is the patron saint of virgins.

I thought little about at the time, for I was woefully ignorant about that particular saint’s VITA. But here is the relevant abbreviated version of her Agnes' biography:

“Saint Agnes was twelve years old when she was led to the altar of Minerva at Rome and commanded to obey the persecuting laws of Diocletian by offering incense. In the midst of the idolatrous rites she raised her hands to Christ, her Spouse, and made the sign of the life-giving cross.”

Some good resources on Agnes and her relationship with Minerva:

Now, I had already proposed that the English Bathum in the guise of British Badon appears in the early Welsh sources precisely because for Aquae places featured the name of pagan goddesses. In the case of Sulis at Bath in Somerset, the deity was associated with Roman Minerva - a virgin goddess.

This made me think of Roman period Minerva dedications in Britain. When I went to RIB to look these up, I found the the site where the most Minerva inscriptions had survived

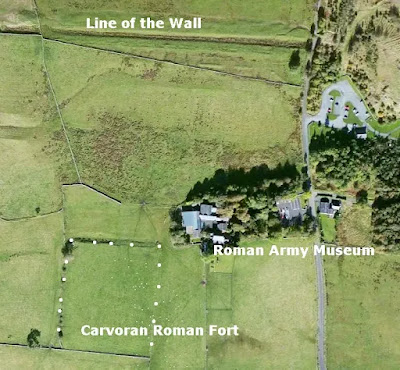

WAS HIGH ROCHESTER. It was also true that Minerva was worshipped at Carvoran on Hadrian's Wall, a place thought my most to derive from a Cumbric Caer + Forwyn (Morwyn), 'Fort of the Maiden', as the Roman Maiden Way road runs from Maiden Castle in Stainmore to Carvoran (

https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1267).

Obviously, in the current context, the dedications to Minerva at High Rochester were the most interesting to me:

High Rochester -

My guess would be that Agned could be substituted in the HB battle list for Breguoin precisely because at some point Bremenium was thought of as the fort of Minerva, and given the objectionable nature of a pagan goddess presiding over the fort or over those men who had garrisoned the fort, the Christian name Agnes was substituted. In this light, Bremenium at High Rochester could be 'Maiden Castle.'

However, given that the only fort in the North that can be reasonably demonstrated to be a Fort of the Maiden in Cumbric, is Carvoran. Maiden Castle in Stainmore, and the Maiden Way Roman road, would be English equivalents drawn upon by the name at Carvoran. It might make more sense to allow Carvoran to be Agned, and for Breguoin to either be a separate Arthurian battle or (as many have suggested) an importation of the Brewyn battle of Urien of Rheged into the HB list.

A Hamian unit was stationed at Carvoran, and they worshipped the

virgin Syrian goddess. According to Richmond (

https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1780, Commentary and Notes) this goddess was worshipped only by coh. I Hamiorum at Carvoran. At Carvoran, this goddess is literally called 'The Virgin.'

RIB 1791: Poem in iambic senarii dedicated to Virgo Caelestis found in the NE of Carvoran. Imminet Leoni Virgo caeles/ti situ spicifera iusti in/ventrix urbium conditrix / ex quis muneribus nosse con/tigit deos: ergo eadem mater divum / Pax Virtus Ceres dea Syria / lance vitam et iura pensitans. / in caelo visum Syria sidus edi/dit Libyae colendum: inde / cuncti didicimus. / ita intellexit numine inductus / tuo Marcus Caecilius Do/natianus militans tribunus / in praefecto dono principis (The Virgin in her place in the heavens rides upon the Lion; bearer of corn, inventor of law, founder of cities, by whose gifts it is the good lot of men to know the gods: she is therefore the Mother of the gods, Peace, Virtue, Ceres, the Syrian Goddess, weighing life and laws in her balance. Syria has sent the constellation seen in the heavens to Libya to be worshipped: thence have we all learned. Marcus Caecilius Donatianus, serving as tribune in the post of prefect by the Emperor’s gift, led by thy godhead, has understood this). Source RIB I p.558.

"The priority for efforts to supervise the Wall curtain itself has received less attention, but one short stretch of the frontier zone in the central sector is identifiable as a consistent focus of activity and innovation: the gap between the Tipalt Burn and the Irthing (Symonds 2017, 39; Fig. 36). Prior to the establishment of Hadrian’s Wall, this stretch was supervised by the fort at Carvoran, and the fortlet at Throp. Further forts and a fortlet shadowed the Irthing as it flowed westwards, while towers were established on both sides of its valley. When work on the mural frontier commenced, the milecastles within the Tipalt-Irthing gap were probably among the first to be completed and manned, and at the very least turrets 48a and 48b are also likely to have been fast-tracked (Hill 1997, 42; Symonds 2005, 76; Graafstal 2012, 150). Construction of the Wall curtain also appears to have been accelerated, while the ditch was unusually substantial (Graafstal 2012, 145–146). Following the fort decision, turrets 44b and 45b – directly east of the eastern lip of this topographical bottleneck – became the most artfully positioned examples known on the Wall. To the west of the gap, where the northern lip of the Irthing valley lies hard to the south of the murus, a fort was established at Birdoswald. It is the milecastles along this strip, numbers 49–54, that appear to have been increased in size when they were rebuilt in stone."

Carvoran was also only a dozen miles east of Camboglanna/Castlesteads, Arthur's Camlann.