While reading up on St. Illtud's churches in Wales, I stumbled upon an interesting ancient cross carved with the names of saints, including those of Illtud and Samuel (Welsh Sawyl). The details of this cross I have pasted below.

It is thought the Samuel in question is the one of Llansawel in Carmarthenshire.[1]

Samuel (Language: Biblical; Gender: male)

RomillyAllen/1889, 124: `The Samuel and Ebisar on the cross of Samson at Llantwit have not been identified; but the latter name is to be seen on the two crosses at Coychurch'.

Rhys/1899, 152: `Who these men were is not known...Samuel appears to have been rather common in early Wales, and in its Welsh form of Sawel it is associated with the Carmarthenshire church of Llan-Sawel'.

Anon/1928, 407: `Samuel appears to have been a not uncommon name at about the time when the cross was made'.

Nash-Williams/1950, 142: `None of the persons named in the inscription are now identifiable'.

first mentioned, 1695 Lhuyd, E.

History: The earliest references to this stone are by Lhwyd in Gibsons Camden, and in Gough's Camden (neither work consulted).

Iolo Morganwg, 1798, reproduced in Allen/1893, 326: `I have already observed that the author of the additions to Camden takes notice only of the monumental stone behind the church erected by Samson to the memory of Iltutus [this stone]. This circumstance proves that the other ancient inscribed stones [including this one] were not then to be seen'.

Rhys/1873, 9: `Aug. 30. -- The rector kindly accompanied me to Llantwit-Major, where we knew there were several inscriptions'.

Westwood/1879, 9: `This is one of the most interesting memorials of the early British Church in existence, commemorating as it does not fewer than four of the holy men, some of whose names are amongst the chief glories of the Principality. It stands in the churchyard of Llantwit, on the north side of the church...This stone was first mentioned by Edward Lhwyd in Gibson's Camden, p. 618. Strange, in the Archaeologia, vol. vi (1782), p. 22, pl. 2, fig. 1--2, gives a very insufficient engraving of it, copied in Gough's Camden, iii. p. 130, pl. 7, fig. 2. In Huebner's work (p. 22) an engraving is given of the inscription of the front of the stone in which the word `anmia' is misprinted `anima,' and with the m of the usual minuscule form'.

Allen/1889, 119: `The earliest notice of the Llantwit crosses occurs in Gibson's edition of Camden's Britannia (1695), the additions to Wales for which work were contributed by Edward Lhwyd, the Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. It is to this eminent antiquary, the pioneer of Welsh archaeology, that we are indebted for the first accurate knowledge of the inscribed stones. The Llantwit crosses have also been described subsequently by Mr. Strange in the Archaeologia, vol.vi (1779), by Donovan in his South Wales (1805), by Mr E Williams, otherwise known as ``Iolo Morganwg'', in the volumes published by the Welsh MSS. Society, and lastly by our old friend and associate, Prof. Westwood, in his standard work on the subject, the Lapidarium Walliae'.

Halliday/1903, 58--64, notes that the stone was eventually moved to its present position in the church in 1903. During this move, the complete outline of the cross was revealed (see form-notes). A cist grave was discovered at the foot of the cross which was considered contemporary with the cross, and as evidence that the cross had been in situ.

RCAHMW/1976, 50: `originally standing in the churchyard N. of St. Illtud's Church, and re-erected in 1903 within the W. nave of the church'.

Geology: Macalister/1949, 156: `stratified sandstone'.

Nash-Williams/1950, 142: `Local grit, apparently Carboniferous'.

RCAHMW/1976, 50: `local grit'.

Dimensions: 3.1 x 0.79 x 0.29 (RCAHMW/1976)

Setting: in ground

Location: on site

Nash-Williams/1950, 140: `All the Llantwit Major monuments are preserved in the church at the W. end of the nave'.

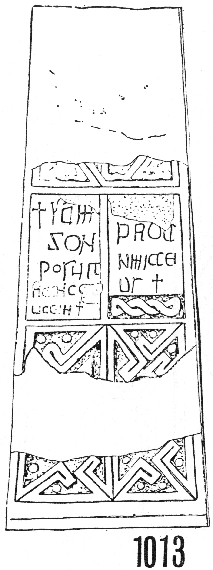

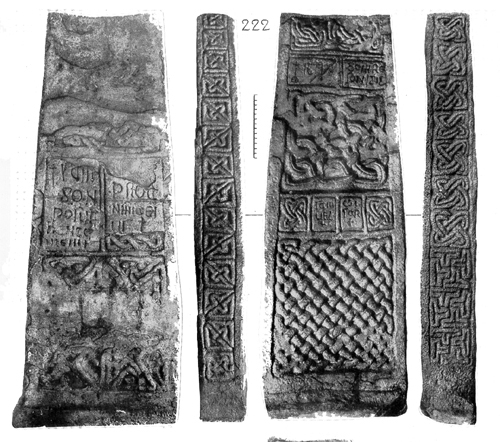

Form: Cramp shaft B

Iolo Morganwg, 1798, reproduced in Allen/1893, 326: `The stone inscribed to Iltutus is the shaft of an ancient cross, at the top of which the mortice still remains, into which the round stone on the top was by a tenon inserted, whereon the cross was sculptured'.

Rhys/1873, 9: `Another stone has its inscriptions separated into small compartments'.

Westwood/1879, 9: `It is an oblong block of stone about 6 feet high, its breadth below being about 29 inches, and above about 23 inches, and it is 9 1/2 inches in thickness'.

Allen/1889, 125: `The last points we have to consider are the forms of the crosses and the character of the ornament. The five sculptured monuments at Llantwit exhibit three different types; the wheel-cross, the rectangular cross-shaft, and the cylindrical pillar. The crosses of Samson, Samuel, and Ebisar, and of Houelt, the son of Res, are of the so-called wheel shape, consisting of a tapering shaft of rectangular section, surmounted by a circular head, shaped like a drum. The head of the first of these two crosses is lost, but the mortice-hole by which it was fixed on still remains; and the curve of the top enables us to conjecture that the diameter of the drum must have been about 3ft.6in. The mortice is double, the centre part being sunk 5 1/2in., leaving shoulders 2 in deep at each side (see wood cut, p. 126.). The shaft is 6ft. 6in. high, 2 ft. 7in. by 1 ft at the bottom, tapering to 1ft. 11 in. by 8 1/2 in. at the top. The bottom is left rough, showing that if was fixed in the ground without any socket stone'.

Rhys/1899, 151: `the pedestal of a cross'.

Halliday/1903, 57--58: `The Cross-shaft of Samson, commonly called the Iltyd Stone, measures 6 ft. from the gound-line upwards, and 4 ft. 2 ins. from the ground-line to the extreme base, which tapers from 12 ins. to 7 ins. in thickness (Fig. 5). The worked portion of the stone terminates in a picker-line, about 3/4 in. in breadth, a few inches below the ground line...There are no signs of either tooling or working in any form. It is simply a glacial boulder turned to account: on one side the surface is rubbed quite smooth, and shows very distinct striations'.

Macalister/1949, 156--157: `a slab...a mortice for a cross remains in the present top'.

Nash-Williams/1950, 142: `Splayed shaft (? of a composite slab-cross), formerly with extended rough butt (4 ft. long) below[2] and a rectangular shouldered mortise in the top (? for the attachment of a separate head).[3] 85" h. above butt x 30" w. and 11" t. at bottom, diminishing to 22" w. and 10" t. at top...The shaft is decorated on all faces with carved patterns in low to medium relief (extensively damaged by flaking), and is also inscribed...The stylistic relationship of this monument to Nos. 159, 303, and 360 has already been noted (p. 116).

[2] See AC, 1903, [Halliday/1903] p. 58 (figured).

[3] For the probable form of the head see p. 115, note 3'.

RCAHMW/1976, 50--51: `Shaft of composite cross, probably disc-headed...The exposed part of the stone...with well-squared angles and splayed faces, stands 2.15m high, the total length with the buried lower part being 3.10m. The main faces taper upwards from 79cm to 58cm in width, and the thickness decreases from 29cm to 24cm. It has carved decoration on all faces, varyingly weathered, and both main faces carry inscriptions.

In the top of the shaft a rectangular mortice has been cut 11.4cm deep, countersunk with wide shoulders 6.4 cm deep, for a separate cross-head now lacking. This most probably took the form of a disc-head, for which there is some evidence in the deliberate concavity of the upper surface[1] and in that the decorative patterns on the narrow sides need to be completed by being continued on the sides of a head of similar width (cf. No. 911). Its size may be estimated by comparison with Nos. 903, 907 and 911 rather than from the degree of curvature of the surviving top surface...The form of the shaft and in particular its decorative patterns are very similar to those on the `Cross of Eiudon' (E.C.M.W. 159), and the two stones may have been carved by the same hand'.

Condition: complete , some

Westwood/1879, 9--10: `The front face has unfortunately been much injured by the scaling off of large portions, nearly the upper half and a portion of the lower division having thus been lost, caused by the climbing of children up the stone. We can only conjecture that the upper part may have contained a cruciform design, or that it may have been surmounted by a wheel cross'.

Macalister/1949, 157: `the surface is, however, badly scaled'.

Folklore: none

Crosses: none

Decorations:

Westwood/1879, 10: `Sufficient remains of the upper part of the lower division of the face of the stone to show that it was ornamented with the curious Chinese-like design (with small raised bosses in the open spaces), of which the complete pattern may he seen upon the cross at Neverne and on that of Eiudon.

The back face of the stone (Pl. IV) is more complete than the front, although both the broad interlaced ribbon designs in the upper part have been injured by exposure to the weather; the lower part is filled by a large design of straight interlaced ribbons like basket-work...The two small compartments at the sides of this inscription [second part of LTWIT/2/2] are filled with the double interlaced oval pattern, which is also used along the upper part of one of the edges of the stone (Pl. III), below which is the well-known pattern formed of four T's, with the bottom of the upright strokes directed to the centre of the pattern. The other edge of the stone has thirteen squares filled with a diagonal and square design'.

Allen/1889, 125--126: `The ornament on the Llantwit stones consists of interlaced and key-patterns arranged in panels of the same class as that found in the Irish MSS. of the ninth and tenth centuries. There is none of the spiral decoration which is characteristic of the earlier MSS., sculptured crosses, and ecclesiastical metal work.

Attention should be particularly directed to three peculiar patterns on the crosses of Samson, Samuel, and Ebisar, -- (1), two oval rings interlaced crosswise; (2), four T's placed in the shape of a fylfot or swastica; and (3) a simple key pattern. Similar designs occur on three other crosses in Wales --- at Golden Grove, Caermarthenshire; and at Nevern and Carew, Pembrokeshire'.

Macalister/1949, 157: `The devices were chisel-cut, and so far as they remain are in good condition... For the details of the ornament, see the illustrations'.

Nash-Williams/1950, 142: `Front. The decoration is disposed vertically in panels: (a) diaper key-pattern (?) (vestiges only); (b) double horizontal panel containing parts of a Latin inscription in five and three lines respectively, reading horizontally (see (1) and (2) below), with a four-lobed plain twist (R.A. 501) in the field below the second inscription; (c) four squares of diaper key-pattern (cf. R.A. 1010 and 1012),[4] with pellets symmetrically disposed in the interspaces. Right. Vertical band of fourteen squares of diaper key-pattern variously disposed (R.A. 99, a characteristic S. Wales motif). Back. Panelled decoration as before: (a) remains of twelve-cord double-beaded plaitwork, with irregular vertical and horizontal breaks; (b) double horizontal panel with a Latin inscription in two parts, each of two lines reading horizontally (see (3) and (4) below); (c) twelve-cord double-beaded plait with irregular breaks (as before); (d) quadruple horizontal panel, the inner compartments containing parts of an inscription each in three lines reading horizontally (see (5) and (6) below), the two outer pairs of interlinked oval rings (R.A. 766); (e) coarse sixteen-cord plain ribbon-plait, with one break. Left. Narrow vertical panel filled with seven pairs of interlinked oval rings (R.A. 766) above and three squares of swastika key-pattern (R.A. 921) below.

[4] The pattern is apparently peculiar to S. Wales'.

RCAHMW/1976, 50: `On the E. face (as when in situ and as now re-set) the decoration forms three main panels in vertical order within plain continuous angle-mouldings. The uppermost panel has almost entirely flaked away, leaving weathered traces of diagonal swastika key-patterns probably arranged in six squares. A shorter panel below, framed and divided vertically by plain beading but not sunken, contains two horizontal inscriptions...The lower part of the right-hand panel is cut back to leave in relief a four-lobed plain twist. The lowest main panel, partly defaced, is formed of four squares of diagonal swastika key-pattern with paired pellets in all the outer segments.

The narrow S. side of the shaft forms one vertical panel, its upper two-thirds containing seven knots of double-beaded intertwining oval loops, the remainder filled with three squares of swastika key-patterns.

The W. face has three main panels of carved ornament separated by two bands of demi-panels with inscriptions. The damaged topmost panel contains irregular double-beaded plaitwork incomplete in itself and formerly continued on the missing cross-head. A plain horizontal beading separates this from a pair of rectangular demi-panels below, each framed by similar beading but not sunken...The central main panel is a square containing ten-cord double-beaded loose plaitwork with unsymmetrical breaks. Below it in a horizontal row are four equal rectangular demi-panels, the two outer ones each filled with a knot of double-beaded intertwined oval loops. The inner demi-panels, framed by plain beading but not sunken, have inscriptions...The lower half of the face forms one large panel filled with regular plain sixteen-cord plait, in which there is one break at the top.

The narrow N. side forms one vertical panel filled with fourteen squares of diagonal key-pattern alternating in direction except that the five upper squares are identical. The top square is incomplete, suggesting that the pattern was continued on the head'.

[1]

While the following is true (passage from The Lives of the British Saints: The Saints of Wales and Cornwall and Such Irish Saints as Have Dedications in Britain, Volume 2, Sabine Baring-Gould, John Fisher, For the honourable Society of cymmrodorion, by C. J. Clark, 1908) -

"The genealogies of the Welsh saints give his [St. Asaph's] father's name as Sawyl Benuchel, the son of Pabo Post Prydain, but in the very early genealogies in Harleian MS. 3859 he appears as "Samuil pennisel map Pappo post priten," with epithet 'Penisel" (of the low head) or "Penuchel" (of the high head). The later genealogists confounded him with the Glamorganshire chieftain (dux), Sawyl Benuchel..."

- it also appears the St. Sawel of Llansawel in Carmarthanshire was confused with Sawyl of the North.

I say this because Llansawel is on the Afon Marlais. The southern Llangadog is by Allt Cunedda, where Sawyl Benuchel was supposedly swallowed up by the earth, but the northern Llangadog is very near another Afon Marlais. See the maps below. Thus it is likely that it was St. Sawyl, possibly the Samuel of the Illtud Cross, who was confused with Sawyl of the North. In other words, there never was a separate southern dux named Sawyl who came to figure in the Life of St. Cadog.

All of this is important because in the Life of St. Cadog it is the 'dux' Sawyl Benuchel who, with his men, commands the food and drink raid on the saint's monastery. In the Life of Illtud, it is the men of the war-chief Illtud who commit this crime.

Llansawel and the Afon Marlais 1

Llangadog North and the Afon Marlais2

Llangadog South and Allt Cunedda