Solsbury Hill

Many scholars have written about Gildas's dating of the Battle of Badon. The history of this lively debate is best found summarized, and dealt with, in

Thomas D. Sullivan, THE DE EXCIDIO OF GILDAS: ITS AUTHENTICITY AND DATE, 1978, pp. 134-157 (link courtesy Professor Marek Thue Kretschmer):

https://books.google.no/books?id=q2U3i1X8B50C&pg=PA155&dq=%22let+us+turn+back+now+to+the+badonic+question%22&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiqt5ng54PbAhXGDSwKHbvUDlEQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=%22let%20us%20turn%20back%20now%20to%20the%20badonic%20question%22&f=false

An even more recent treatment of the date of Badon can be found here:

https://people.clas.ufl.edu/jshoaf/2014/07/07/gildas/

An even more recent treatment of the date of Badon can be found here:

https://people.clas.ufl.edu/jshoaf/2014/07/07/gildas/

The consensus, plainly, is that the Battle of Badon happened when Gildas was born, i.e. 44 years ago, with one month of that 44th year having already passed at the time of his writing. According to P.C. Bartram (A CLASSICAL WELSH DICTIONARY), Gildas was born c. 490 A.D.. Other scholars put his birth date closer to 500 A.D. or even into the second decade of the 6th century.

I asked Professor Alexander Andrée, Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto, whether another reading of the DE EXCIDIO passage on Badon and Gildas's birth might be possible:

"Could he [Gildas] be writing about the battle a month after the battle took place, a battle which, as it happened, had fallen exactly 44 years after he had been born?"

To which the Professor responded:

"The crucial passage is “mense iam uno emenso,” literally translating as, “with one month already having been measured out.” But the word “iam” may be translated in a host of different ways: already, at last, by this time, just, etc. So, yes, I would say that there is a certain ambiguity about the passage. Maybe translating it as you suggest is stretching it little too far, but I wouldn’t say it’s entirely impossible.

It is an unfortunately dense passage. I don’t have any stakes in the question and would translate the passage, “… quique quadragesimus quartus (ut noui) orditur annus mense iam uno emenso, qui et meae natiuitatis est,” as, “… and which year, the 44th <year> as I know it, began with one month already having passed, which is also <the year> of my birth.”"

From Professor Gernot Wieland:

"Here is a literal translation of the passage in question:

quique quadragesimus quartus (ut noui) orditur annus mense iam uno emenso, qui et meae natiuitatis est

"which begins the forty-fourth year (as I know) with one month already having passed, which is also (the year) of my birth."

The first and second "which" refers to the "annus" of the battle of Mount Badon. In other words, the Battle of Mount Badon began the year which is now in its forty-fourth year.

Since no "dies" = "day" is mentioned, and since the "qui" in "qui et meae natiuitatis est" must refer to "annus," a birthday must be ruled out,

So, no matter how I turn the phrase, I always come up with the same conclusion: the battle took place forty-four years and one month ago, and forty-four years ago is also the year of Gildas birth. And to answer your question directly: I see no way that he could be writing about the battle one month after it took place, nor is there any indication that the battle took place on his forty-fourth birthday, since no "day" is mentioned."

The opinion of Professor Els Rose:

"I gather that you relate qui ... est to mense rather than annus, which is a possibility, although I would be inclined to link the relative pronoun to the subject of the preceding clause rather than to the noun in the ablative absolute. Also, with the sequence sed ne nunc the narrative seems to create a distance from the period of the battle of Badon Hill and the time of writing, so that it would make sense to place that battle in a more or less distant past (the period of the author's birth)."

Professor Michael Herren, who has actually worked on the text, has a somewhat different take on the correct translation of the problematic passage:

"Ex eo tempore [from that time] nunc cives, nunc hostes vincebant [now our citizens, now our enemies were victorious] -- ut in ista gente expireretur dominus solito more praesentem Israelem, utrum diligat eum an non -- [ -- so that the Lord might test in his people the present Israel in his accustomed way, (as to) whether it loves him or not--] usque ad annum obsessionis Badonici montis novissimaeque ferme de furciferis non minimae stragis [to the year of the siege of Mount Badon and almost the last but not least carnage involving those rogues], quique quadragesimus quartus (ut novi) orditur annus mense uam uno emenso [which year begins already the 44th less one month] qui et meae nativitatis est [and also the year of my birth].

Paraphrase: From that time (indefinite) when things were going this way and that (that the Lord blah blah) to the Battle of Mount Badon, which was nearly the last one with those villains, is, as I know, 44 years less one month.

The time is counted as 44years less a month from some unspecified time (ex eo tempore) to (usque ad) the Battle of Mt. Badon, which happens to coincide with the year of Gildas's birth. An exact parsing of the syntax (which I sent you; see above) bears this out.

Incidentally, the Welsh Annals give the Battle of Badon as 516 C.E., which would mean that G. was 44 in that year, and would have been born in 472. If the Annals are right, he was writing in 516 or some time afterwards. However, scholars are sceptical of annalistic dates before the 7th century.

See Thomas D. O'Sullivan'sstudy, The De Excidio: Its authenticity and date (Brill, 1978), last chapter. O'S. takes the eo tempore as a reference to the victory of Ambrosius Aurelianus."

From Professor Gernot Wieland:

"Here is a literal translation of the passage in question:

quique quadragesimus quartus (ut noui) orditur annus mense iam uno emenso, qui et meae natiuitatis est

"which begins the forty-fourth year (as I know) with one month already having passed, which is also (the year) of my birth."

The first and second "which" refers to the "annus" of the battle of Mount Badon. In other words, the Battle of Mount Badon began the year which is now in its forty-fourth year.

Since no "dies" = "day" is mentioned, and since the "qui" in "qui et meae natiuitatis est" must refer to "annus," a birthday must be ruled out,

So, no matter how I turn the phrase, I always come up with the same conclusion: the battle took place forty-four years and one month ago, and forty-four years ago is also the year of Gildas birth. And to answer your question directly: I see no way that he could be writing about the battle one month after it took place, nor is there any indication that the battle took place on his forty-fourth birthday, since no "day" is mentioned."

The opinion of Professor Els Rose:

"I gather that you relate qui ... est to mense rather than annus, which is a possibility, although I would be inclined to link the relative pronoun to the subject of the preceding clause rather than to the noun in the ablative absolute. Also, with the sequence sed ne nunc the narrative seems to create a distance from the period of the battle of Badon Hill and the time of writing, so that it would make sense to place that battle in a more or less distant past (the period of the author's birth)."

Professor Michael Herren, who has actually worked on the text, has a somewhat different take on the correct translation of the problematic passage:

"Ex eo tempore [from that time] nunc cives, nunc hostes vincebant [now our citizens, now our enemies were victorious] -- ut in ista gente expireretur dominus solito more praesentem Israelem, utrum diligat eum an non -- [ -- so that the Lord might test in his people the present Israel in his accustomed way, (as to) whether it loves him or not--] usque ad annum obsessionis Badonici montis novissimaeque ferme de furciferis non minimae stragis [to the year of the siege of Mount Badon and almost the last but not least carnage involving those rogues], quique quadragesimus quartus (ut novi) orditur annus mense uam uno emenso [which year begins already the 44th less one month] qui et meae nativitatis est [and also the year of my birth].

Paraphrase: From that time (indefinite) when things were going this way and that (that the Lord blah blah) to the Battle of Mount Badon, which was nearly the last one with those villains, is, as I know, 44 years less one month.

The time is counted as 44years less a month from some unspecified time (ex eo tempore) to (usque ad) the Battle of Mt. Badon, which happens to coincide with the year of Gildas's birth. An exact parsing of the syntax (which I sent you; see above) bears this out.

Incidentally, the Welsh Annals give the Battle of Badon as 516 C.E., which would mean that G. was 44 in that year, and would have been born in 472. If the Annals are right, he was writing in 516 or some time afterwards. However, scholars are sceptical of annalistic dates before the 7th century.

See Thomas D. O'Sullivan'sstudy, The De Excidio: Its authenticity and date (Brill, 1978), last chapter. O'S. takes the eo tempore as a reference to the victory of Ambrosius Aurelianus."

These kinds of responses, as it turned out, were kind and generous. Of over a dozen top experts in Medieval Latin I consulted on this question, all leaned heavily on the prevailing interpretation, i.e. that Gildas was born on the day of the battle. And that means Badon happened c. 500, +/- 10-20 years.

Some responses, on the other hand, were quite terse. For example:

"The Latin doesn’t say that. It says the battle happened in the same year that he was born." [Professor Robert Babcock]

We can try to argue, without justification, that an error of transmission occurred during some phase of the copying of the MS., but this is something we cannot prove. It would be merely a wild guess, in fact, and a totally insupportable one at that.

But I believe I have found a way out of our difficulty.

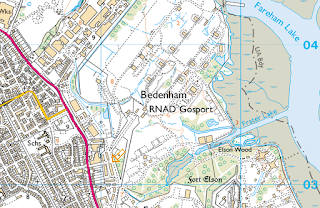

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle mentions a battle being fought in 501 A.D. A chieftain involved in the battle was named Beida (West Saxon Bīeda, Northumbrian Bǣda, Anglian Bēda). Beida's name is preserved in Bedenham on Portsmouth Harbour.

What I'm going to propose, rather boldly, is that Gildas's 'Badon' originally was the battle featuring Bieda/Beda. Now, let me hasten to add this does not mean I'm saying Arthur's Badon is a fiction or is based on an otherwise rather inconsequential battle at Portsmouth.

Instead, I'm suggesting that the REAL Badon, Arthur's Badon, i.e. Bath of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for the year 577 (see my book THE BEAR KING: ARTHUR AND THE IRISH IN WALES AND SOUTHERN ENGLAND), was at some point in the transmission of manuscripts wrongly substituted for the Beden- battle of Gildas.

It is only purists who will object to this idea. Although Gildas (and other early sources, such as the HISTORIA BRITTONUM) have been subjected to merciless criticism in the modern era, there are still those who hold to the idea that the veracity of Gildas's DE EXCIDIO is to be upheld. This despite major problems with the text, such as the inclusion of Ambrosius Aurelianus (who, as I have shown in detail elsewhere, was a 4th century figure). People clinging to this kind of of inflexible view will never be able or willing to accept the idea that Badon was wrongly related to the Portsmouth battle of 501 A.D. They will continue to look for Arthur where he does not exist, precisely because they have temporally dislocated him.

I suspect many philologists will also object to the notion. They will insist that Bieda/Baeda/Beda place-name cannot have been mistaken for Bath. Well, this may be true in our time, when our knowledge of the languages involved and their development has become so advanced. But in the ancient period sound-alike etymology and fanciful etymology were common practices. Add to this the difficulty of going from English to Welsh (or to Irish) and I do not think this kind of confusion is that unlikely. I would add in concluding that Badon, as it stands, is still - speaking from a strictly linguistic standpoint - a British version of English Bathum, and as such may have been thought of by the Welsh as Bath.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.