Constantine III, AV Solidus

Quite some time ago, I fooled around with the idea that Uther Pendragon was, in reality, a Welsh attempt at the Magister Utriusque Militiae title given to the 5th century Gerontius. For those who would like to read my full treatment of the proposed identification, please see the following link:

I abandoned the notion because it was hard to demonstrate any parallels at all between Geoffrey of Monmouth's notably fictional account and the historical narratives. But I now think there may be another reason to consider the possibility.

Gerontius raised up as emperor one Maximus. The sources are unclear as to whether this man was a son of the British chieftain or merely a "domesticus". But we do know that this Maximus, probably the same as the one called Maximus Tyrannus around 420 A.D., was based in Spain. His imperial name was doubtless chosen to copy that of the Spaniard Magnus Maximus, a previous usurper (d. c. 388) who was hailed by British troops.

This previous Maximus is known in Welsh tradition as Macsen Wledig or Maximus the Tyrant!

I've demonstrated before that the Ambrosius brought into connection with Vortigern (a name which means 'supreme king') was either the Prefect of Gaul father of St. Ambrose (who had the same name and might conceivably have gone to Britain with Constans I in 343) or a conflation of the father and the saint. We know that the historical St. Ambrose interacted with Magnus Maximus. The true date of Ambrosius is preserved in the HISTORIA BRITTONUM, which has this warleader fight against the grandfather of Vortigern.

I've demonstrated before that the Ambrosius brought into connection with Vortigern (a name which means 'supreme king') was either the Prefect of Gaul father of St. Ambrose (who had the same name and might conceivably have gone to Britain with Constans I in 343) or a conflation of the father and the saint. We know that the historical St. Ambrose interacted with Magnus Maximus. The true date of Ambrosius is preserved in the HISTORIA BRITTONUM, which has this warleader fight against the grandfather of Vortigern.

Constans II (named for Constans I) was murdered by Gerontius, but at the time Maximus the Tyrant was emperor. The general employed barbarian troops for the deed. In Geoffrey's tale, it is Vortigern who has Constans killed by Picts.

So what I'm suggesting is this: not only did Constantine III and Constans II become merged in popular tradition with their earlier namesakes, with Ambrosius being literally moved up in the chronology as a result, the same conflation occurred between Vortigern, Magnus Maximus and Maximus the Tyrant. The only "big player" missing in this major distortion of fact is the British general Gerontius.

Should we, then, seriously entertain Gerontius magister utriusque militiae as Uther Pendragon? And, if we do, what do we make of a man who died in 411 as the father of an Arthur who fights his two most famous battles in 516 and 537?

Well, as I've said before, there appear to have been later Gereints in Dumnonia. If we can have a remarkable confusion of identical names with the other leading figures of the day, then we can very easily allow for the possibility that the Gerontius who died in 411 had a namesake whose floruit was more towards the last half of the 5th century.

Well, as I've said before, there appear to have been later Gereints in Dumnonia. If we can have a remarkable confusion of identical names with the other leading figures of the day, then we can very easily allow for the possibility that the Gerontius who died in 411 had a namesake whose floruit was more towards the last half of the 5th century.

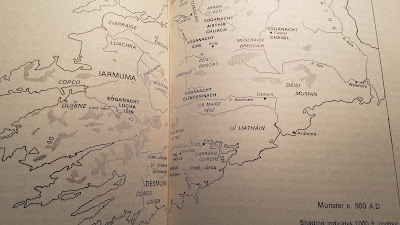

Needless to say, if we accept a mid-5th century Dumnonian Gereint as Arthur's father, the whole Arthurian arena shifts back to Devon, Cornwall and Somerset. Which is where tradition has pretty much always centered it.

Map Courtesy ARTHUR THE KING IN THE WEST by R. W. Dunning