Cadbury Castle on the River Cam, Somerset

"Right at the South end of South Cadbury Church stands Camelot. This was once a noted town or castle, set on a real peak of a hill, and with marvellously strong natural defences..... Roman coins of gold, silver and copper have been turned up in large quantities during ploughing there, and also in the fields at the foot of the hill, especially on the East side. Many other antiquities have also been found, including at Camelot, within memory, a silver horseshoe. The only information local people can offer is that they have heard that Arthur frequently came to Camelot."

John Leland, 1542

[NOTE: Since writing this piece, I realized that Uther as Pen Kawell or 'Chieftain of Kawell' could be related to the Camel[l] names hard by Cadbury Castle in Somerset. These names are spelled such from the time of the DB onwards. I received confirmation for the possibility from the likes of Dr. Simon Rodway at The University of Wales. The letters w/v/u/m are often interchangeable, and so kawell may be a simple error for kamell. If so, we may have direct evidence from the 'Marwnat Vthyr Pen' poem for Uther's connection with Cadbury Castle. I had already shown at https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2021/09/arthur-and-cadwy-in-region-of-carrum.html that Arthur and Cadwy at Carrum was probably a relocation for Cadbury bordering on Cary.]

A potential shocker here, which I am reserving judgment on for now. Just thought I would put it out there.

I was finishing up work on all possible variant readings for the Pen Kawell of the Uther Pendragon elegy poem. At the same time, I was reviewing some old pieces I wrote on a very revolutionary idea pertaining to the nature of the Uther Pendragon name/epithet. Some members of my blog site may remember the following:

In brief, I had entertained the notion that Uther Pendragon (noting that uther could be spelled uter; cf. Latin uter) was an attempted Welsh rendering of the magister utriusque militiae title of the early 5th century British general Gerontius. And that while that man was not Arthur's father, it may well be that the later Dumnonian Geraint, perhaps named for the more famous Gerontius, was the father of the hero.

In the first link listed above, I commented on Arthur's association with a Dumnonian Geraint thusly:

There is yet another possible reason why Arthur is found in the Geraint poem on the Battle of Llongporth. In 658 A.D., according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Cenwalh battled the Welsh at Penselwood in Somerset and drove them to the River Parrett. It cannot be a coincidence that Langport lies on the Parrett. A Geraint is mentioned as fighting Ine and Nunna in 710, but the location is not given.

Notice that directly between Penselwood and Langport lies South Cadbury, site of the famous Cadbury Castle hillfort that traditionally has been associated with Arthur. The River Cam at South Cadbury is a tributary of the Yeo and becomes the Parrett at Langport.

If a Geraint fought here, then we may have some evidence that his fortress was Cadbury Castle. Geraint had a son named Cadwy and I've elsewhere written about this name and its connection to the various Cadbury forts (see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2019/12/cadburys-and-personal-name-badda.html). Arthur is paired with Cadwy at Dindraithou (see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/12/dindraithou-darts-castle-at-watchet.html and https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2019/12/cadburys-and-personal-name-badda.html). This latter fort, while not truly Arthurian, is in the same region of England as the several Cadbury forts.

What came out of this idea was a reappraisal of Arthur's tradition pedigree:

THE DUMNONIAN GENEALOGY OF ARTHUR AND GEREINT

From http://christophergwinn.com/arthuriana/arthurs-pedigree/, we can compare the various gene-alogies relating to Arthur and Geraint:

MOSTYN MS 117, 5

Arthur-Vthyr-Kustenin/Kwysdenin

BONEDD YR ARWYR, 30a

Arthur-Uther-Kustenin Vendigeit

BONEDD YR ARWYR, 30b

Arthur-Vthyr bendragon-Kustenin

BONEDD Y SAINT, 76

Geraint-Erbin-Custennin/Kwysdenin Gornev

To which we may add that of the Life of St. Cybi, thought to be a "mishandling" of the material by John Koch:

Erbin-Geraint-Custennin

We can see that in some lines of descent, Uther is the son of Constantine, as per Geoffrey of Monmouth. In others, Geraint is made the son or grandson of Constantine.

I suspect our clue to repairing this genealogy is to look a bit harder at what Koch called above “a sloppy mishandling of genealogies” in the Life of St. Cybi. There Erbin is called the son of Gereint rather than the latter’s father. What I would propose is this: the original genealogy ran

[Arthur son of] Gereint (Uther) son of Erbin son of Gerontius MVM

with the magister utriusque militiae rank of Gerontius being transferred to the Gereint who claimed to be his grandson.

Now, again, I made nothing of this at the time, besides noting that it appeared to be an interesting nod to the tradition that insists Arthur belongs to the "Summer Country."

But in looking again at Pen Kawell of the MARWNAT VTHYR PEN, an elegy poem in the Book of Taliesin about Uther, I happened upon a place-name which seemed more than a little interesting: the Cale river and associated Wincanton. Ekwall mentions the early forms of the river name as Cawel, Wincawel, and calls it a "pre-English river-name." Mills has “Celtic river-name of uncertain origin, but prefixed by *winn ‘white’. Watts compares the name to Cornish cawal, Welsh cawell ‘basket, creel, pannier’.

Cawel and Wincawel, or the White Cawel (Win- being from Welsh gwyn) were different branches of the Cale.

[It was not necessary to try and force kawell into Camel, as I had once done, knowing that w could easily become m in some MSS. The problem with the Camel place-name is that it is attested first in 1086 in the Domesday Book. Before then it was Cantmael. My previous discussion regarding Camel and kawell with Dr. Simon Rodway of The University of Wales ran like this:

"I was wondering about that 'pen kawell' in the Uther elegy poem...

As Cadbury Castle (said by Leland to be Arthur's fort) is as early as the DB camel, camelle, could Uther here be saying either he was 'chief of Camel' or that the place was called Pen Camel because it was a hill?

Pretty much, I'm just wondering about the possibility LINGUISTICALLY."

His response?

"It's possible."]

The River Cale (Cawel) in Relationship to Cadbury Castle, Langport, Glastonbury and Penselwood

If Uther is claiming the River Cale/Cawel for himself, then we cannot ignore its proximity to Cadbury Castle, Langport, Glastonbury and Penselwood.

If we go with this "possible" interpretation of kawell, i.e. allowing for the word to be the river in question, then we can translate the relevant lines of the Uther elegy in this way:

Neu vi luossawc yn trydar:

It is I who commands hosts in battle:

ny pheidwn rwg deu lu heb wyar.

I’d not give up between two forces without bloodshed.

Neu vi a elwir gorlassar:

It’s I who’s styled ‘Gorlassar’ [= the Galfridian Gorlois]: (1)

vy gwrys bu enuys y’m hescar.

my ferocity snared my enemy.

5 Neu vi tywyssawc yn tywyll:

It is I who’s a leader in darkness:

a’m rithwy am dwy pen kawell.May God transform me, Chief of the River Cale [or, May God transform me at the Head of the River Cale; note that pen in Welsh can also denote a sea promontory similar to Geoffrey of Monmouth's Tintagel Head, reputed birthplace of Arthur. Uther may be calling himself Gorlassar/'Gorlois' at Camel. There is a Pen Hill only 1000 meters to the east of Cadbury Castle. According to Ekwall, this aet tham Paenne 1065 Wells is British pen. Pen Ridge near the source of the Cale is a significant archaeological site. For details on this last see https://st12.ning.com/topology/rest/1.0/file/get/2058152523?profile=original. Penselwood was originally called Peonnum, thought to be a dative plural of OE *penn, itself from British pen 'hill' (Ekwall). The Cale rises in Coneygore Wood, to the north of the village of Penselwood. Just to the north of Pen Ridge is Pen Hill with Kenwalch's Castle hillfort. For the listing of this monument see https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=202653&resourceID=19191. Other pen place-names are to be found near Penselwood (e.g. Pen Forest, Penhouse Farm). Pen Pits are ancient quern quarries (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1006139. The is even a prominent hill called Penn near Yeovil, as well as Pendomer, showing how common the place-name element is in this area, once the boundary zone between Dumnonia and Wessex.] (2)

Neu vi eil ka[n]wyl yn ardu:

It’s I who’s like a star [fig. a leader; this is probably the origin of the dragon-headed star

in Geoffrey of Monmouth's pseudo-history] (3) in the gloom:

ny pheidwn heb wyar rwg deu lu.

I’d not give up without bloodshed [the fight] between two forces.

What is attractive about Uther Pendragon as a reflection of a Dumnonian Geraint who himself had been confused with his namesake, the Magister Utriusque Militiae Gerontius, is that we are no longer forced to resort to applying the name/epithet 'Terrible Chief Warrior or Chief of Warriors' to other known historical entities who have their own separate names. What I mean by this is that there has been the tendency (and I have been guilty of this as well!) to interpret Uther Pendragon not as a proper name + epithet, but as a sort of heroic title that was applied to someone else. This method of identification brings with it many problems, not least of which is that one can choose to identify Uther with pretty much anyone. In the case of Gerontius/Geraint, however, the title really is a known Latin military rank that was applied to a recognized historical person.

If Arthur belonged at Cadbury Castle, as the tradition recorded by Leland in the 16th century claims, then anyone searching for Arthur elsewhere (like in the North, which is the currently fashionable location) is on the wrong track. Instead, we would be viewing Arthur as a distinctly southern counterpoint to the English hero Cerdic of Wessex. And, indeed, I once thought that several of the Welsh names for Arthur's battle sites matched those of Cerdic's.

If nothing else, the above speculation shows us just how hazardous Arthurian theorizing can be. Arthur is a slippery hero, which is exactly why so many refuse to acknowledge his historicity and consign him to the realms of folklore and literary invention.

I would hasten to add that if Cadbury Castle is the Arthurian center, we must not be so quick to dispense with the Glastonbury site as 'Avalon.' In the past, I have done everything in my power to remove the glamor from Glastonbury, convinced as I was the Arthur's burial there was spurious tradition. Do we need now to take another look at it as the real burial place of the king?

Maybe. But first we do need to get past the probable source of Geoffrey of Monmouth's apple-island, the Cornish Guerdevalan/Gerdavalan (see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/03/the-avalon-of-geoffrey-of-monmouth.html).

(1)

Marged Haycock's note on gorlassar:

gorlassar Cf. PT V.28 Gorgoryawc gorlassawc gorlassar, rhyming with escar,

as here; again PT VIII.17 goryawc gorlassawc gorlassar. Both passages are

corrupt. PT 98 suggests ‘clad in blue-grey armour’ or ‘armed with blue-grey

weapons’, following G and GPC who derive it from glassar ‘sward, turf, sod’

rather than llassar ‘azure’, etc. (see GPC s.v. llasar), presumably because one

would expect *gorllasar. That may indeed have been present, with l representing

developed [ɬ]. Llassar is rhymed with casnar, Casnar (cf. line 10 casnur) in CBT

III 16.55, VII 52.14-5. On the personal names Llasar Llaes Gygnwyd, OIr

Lasa(i)r, calch llassar ‘lime of azure’, etc., see Patrick Sims-Williams, The Iron

House in Ireland, H. M. Chadwick Memorial Lecture 16 (Cambridge 2005), 11-

16; IIMWL 250-7.

However, the Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru says -

gorlasar

[gor-+glasar, H. Wydd. for-las(s)ar ‘tanllwyth mawr, tanbeidrwydd mawr’ ac fel a. ‘disglair, tanbaid’]

Associated with Old Irish forlas(s)ar, great blaze, great radiance.

When I asked Dr. Simon Rodway of The University of Wales about forlassar, he replied:

"GPC is misleading here. If gorlasar is in any way connected with OI forlassar, then it must contain llasar, not glasar (‘sward, turf, sod’ < glas ‘blue, green’ + ar ‘tilled land’). However gor + llasar should give *gorllasar as ll does not mutate after r. One could invoke Old Welsh orthography here in which ll is represented by l. Alternatively, glasar could have developed as a hypercorrect variant of llasar due to a folk etymology connection with glas ‘blue’.

Llasar could be a borrowing of Irish lasair, as GPC says. I suspect that we have a number of different items which have become mixed together here – Latin lazur, Irish lasar + perhaps Med. Latin lazarus ‘beggar, leper’ < the Biblical Lazarus.

Patrick Sims-Williams discusses this in chapter 9 of his Irish Influence on Medieval Welsh Literature (Oxford, 2011)."

In terms of the context of the poem, with Uther presenting himself as a 'leader in darkness" and "a candle/star in the gloom", a word akin to Irish forlassar makes a great deal more sense that wearing blue-enameled weapons and/or armor.

(2)

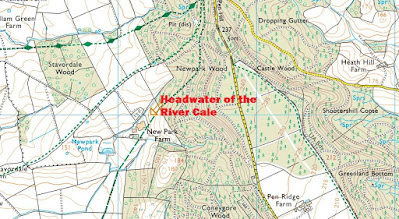

My best guess for Pen Kawell is that this represents either a general term for Pen Ridge - the long ridge running north to south and from which the River Cale rises - or it is a more specific term for Kenwalch's (= Cenwalh's) Castle on Pen Hill. While the main branch of the Cale rises in Coneygore Wood next to Pen Ridge Farm, another headwater issues from just below the hillfort. Kenwalch's Castle is usually identified with the Peonnum of the ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE. To demonstrate what I am talking about, please see the following two maps.

To demonstrate how important Pen Ridge was, I quote here from the study cited above (https://st12.ning.com/topology/rest/1.0/file/get/2058152523?profile=original):

In 652 AD on the West-Saxon frontier with Dumnonia, Cenwealh made a breakthrough against the Dumnonii defensive lines at the battle of Bradford-upon-Avon and more land was expanded as Wessex territory. Dumnonia was reduced further west, now its entire eastern half had become part of Wessex. The Chronicle then records a battle between Cenwealh and the Dumnonian Britons in its entry for 658 AD, the Battle of Peonnum took place on Pen Ridge; “the Dumnonians had angered Cenwealh by convening rebellion and demanding ancient liberties be restored”, (Bede). The two forts at Peonnum had long been the gateways into Selwood Forest; and the ridgeline was the old Dumnonian border with Wessex. "Here Cenwealh fought at Peonnum, where he thrashed the Britons, causing them to flee as far as the River Parret", (Bede). This is why the local folklore of ‘Cenwealh’s Camp’ is still told today. The Dumnonians that had remained in the area, now part of Wessex and under West-Saxon rule were protesting. These rebel Britons rallied their forces here at the old boundary site on Pen-Ridge. It was a good spot for a battle, where the rebels most likely rather hastily re-fortified the abandoned Castle-Wood hill fort in 658 AD and waited for Cenwealh to arrive. The battle was one-sided as Cenwealh chased the Britons thrashing them for nearly fifteen miles as far as the river Parret (Yeovil), back to their own lands and out of West-Saxon territory for ever more. Cenwealh is said to have camped at Castle-Wood around this time, guarding the old frontier gateway and boundary for a brief period, for it was a good strategic site, overlooking Selwood forest, Glastonbury Tor and his enemy the Dumnonians to the west. It is not clear how long he stayed in camp, his advance into the British south-west is obscure, although Cenwealh’s relations with the Britons were not always hostile, and he was reported to have endowed British Monasteries at both Sherborne and Glastonbury around this time. Some sixteen years after Cenwealhs’ death, Ine a West-Saxon nobleman finally became King of Wessex again, from 688 to 726 AD. He successfully established Wessex as a true kingdom by creating the ‘shires’, and a code of laws. To mark territory for three of these ‘shires’, Ine used the old natural boundary divides at Peonnum for; Wiltshire, Hampshire (later Dorset) and Somersetshire. During his reign Ine continued to be at war with Geraint, King of Dumnonia.

I should not neglect to add that pen in Welsh, at any rate, could be used of the source of a stream or river, i.e. a river-head. Pen Cawel could, then, designate the place where the river Cawel rises.

(3)

Dr. Simon Rodway has informed me that the MS.'s kawyl could represent an error for cannwyll:

"Yes, that’s possible. A copyist might have missed an n-suspension over the a, and single n for double nn is quite common in Middle Welsh MSS."

Three things make me a bit uneasy.

1) This requires positing an n-suspension. These do occur occasionally in medieval Welsh MSS, but they are very rare.

2) The single l would mean suggesting an Old Welsh exemplar, for which there is no other clear evidence in the poem. Elsewhere the scribe has ll where needed, so if he was copying from an examplar with l for ll, then this would be the only occasion on which he didn’t correctly modernize.

3) Supposing an n-suspension would only allow us to restore one n. In an OW form, one would expect nt, nh or perhaps nn, but not n.

Overall, emendation to Sawyl, while totally speculative, involves less issues (eye-skip to kawell in the previous line), and eil Sawyl, ‘a second Samuel’ gives plausible sense."

Earlier, Dr. Rodway had explained how an eye-skip could have occurred in this instance:

"It can’t be a case of miscopying a letter, but it could be eye-skip - when a copyist’s eye skips inadvertently to another nearby word resulting in an error. In this case, he would have eye-skipped to the preceding line's 'kawell' to get the /k-/ fronting what should have been 'sawyl'. Was not an uncommon error, so quite plausible. Also, kawell and kawyl are unlikely to be the same word. The poets avoided repeating words in consecutive lines. In cases where this does occur (v rare) it could be scribal error."

In THE BOOK OF TALIESIN, there is a famous prophetic poem called 'Armes Prydein Vawr.' Line 88 of that poem says of Cynan of the Prophecies:

canhwyll yn tywyll a gerd genhyn.

a candle in the darkness goes with us:

The editor and translator Sir Ifor Williams has in his 'Vocabulary' for the poem:

canhwyll nf. candle ( = hero) 88

This is a near perfect match for the Uther elegy's 'kawyl yn ardu.'

For this reason I'm settling once and for all on kawyl not as Sawyl, but as cannwyll, a word that could mean 'star' (transf.) and 'leader' or 'hero' (fig.). We can thus conclude that it was here that Geoffrey of Monmouth got his idea for Uther's star, just as he got his idea for Gorlois from the gorlassar epithet applied to Uther.

From the GPC:

cannwyll

[bnth. Llad. Diw. cantēla < candēla, H. Grn. cantuil, Llyd. C. cantoell, Gwydd. coinneal]

eb. ll. canhwyllau.

a Darn silindraidd o wêr neu gŵyr wedi ei wei-thio o gwmpas pabwyryn ac a ddefnyddir i roi golau, yn dros. am seren, haul, lloer, llusern, lamp, &c.; yn ffig. am oleuni, disgleirdeb, cy-farwyddyd, arweiniad, arweinydd, arwr, y pen-naf, y rhagoraf, &c.:

candle, luminary, transf. of star, sun, moon, lamp; fig. of light, brightness, instruction, lead-er, hero, choicest or best of anything.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.