Uther Pendragon

By now my readers know that from time to time I find it valuable to reflect back upon my own former Arthurian theories. One such proposed that the name/epithet Uther Pendragon was, in fact, a fairly standard folk etymology derived by the Welsh from the Roman military title 'Magister Utriusque Militiae.' While on the surface this seemed rather ridiculous, I was encouraged to further develop the idea by scholars like Professer Peter Schrijver, who thought it possible.

I had suggested the Uther Pendragon = MVM equation for a number of reasons. First, when reading the ever unreliable 'history' of Geoffrey of Monmouth, I noticed that one of the big players of the time period was missing - namely, the great general Gerontius, who had served under Constantine III prior to betraying the usurping emperor. Gerontius was a Briton, and he held the title of MVM. While he was slightly too early to have been Arthur's father, he had later sub-Roman namesakes (Geraints) in Dumnonia, one of whom could easily have been Uther. It was not unreasonable to assume that such a namesake may have become confused with the earlier, more famous Gerontius, and the MVM rank of the latter became attached to the Dark Age figure.

The nice thing about this theory is that is allowed us to accept the preserved tradition on Arthur as having Dumnonian connections. The modern propensity has been to move away from this tradition, and I have myself been guilty of contributing to that.

The problem for Arthurians has always been the name/epithet Uther Pendragon. While it seems pretty straight-forward (for we have other examples of a personal name that is also simply a Welsh adjective, followed by a heroic or at least a descriptive epithet), there is the tendency to seek to identify this chieftain with another known, attestable personage. This is done, supposedly, to add validity to Arthur's historicity.

There are always problems with such identifications. For instance, when I sought to identify Uther with Sawyl Benisel, I was faced with the need to explain why a famous Northern chieftain with a perfectly good name and epithet already would have another name and epithet foisted upon him. I could get away with doing so only by supposing that Sawyl (whose name may be preserved in Samlesbury near the Ribchester fort of the Sarmatian veterans) had been linked in legend to the draco standard, known to be a special attribute of the Sarmatians. 'The Terrible Chief-dragon(s)' could then designate his relationship with the draco, or even with the old Roman rank of magister draconum. Alas, this argument was markedly flawed, as Welsh scholars know that the word dragon in early Welsh heroic poetry is a metaphor for a warrior.

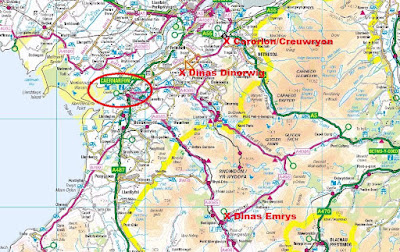

Another example was Uther Pendragon as Cunedda (the Irish Cuinedha mac Cuilinn/the Gewissei Ceawlin/the Wroxeter Stone Maqui-coline). Why alter such a famous man's name at all? I could only explain that by pointing to the dragons of Dinas Emrys (perhaps partly traceable to the double snake standard of the Segontium Roman garrison) - in which case we were still replacing one proper name with another - or to an effort to conceal Cunedda's/Ceawlin's identity because the English had claimed him as their founder of Wessex. In the same way, I had reasoned, Arthur was used by the Welsh rather than Ceredig son of Cunedda. After all, Cerdic of Wessex had been co-opted as an English hero. Or, perhaps, Uther Pendragon was invented because knowledge that Cunedda = Ceawlin (two different names, after all!) were the same person was forgotten. In this scenario as well, though, we would not expect one personal name to be replaced by another.

This problem with the Uther Pendragon name/epithet continues to haunt me (obviously, as I've spilt a lot of ink on the subject). Why, then, might the Magister Utriusque Militiae solution be any more acceptable than anything else that has been put forward, by myself or others?

Well, precisely because the general Gerontius had proven to be a traitor to Constantine III, and had himself suffered an ignominious end. It seems very plausible that in order to "disguise" him, his title was substituted for his name. In this scenario, at some point he was referred to as the MVM. But over time, folk etymology produced Uther Pendragon. Alternately, the title was mistakenly taken as a name at some point and thus separated from Gerontius, creating, quite literally, a new entity.

In either case, we can justify seeing in Uther Pendragon a Welsh rendering (and garbling) of the Magister Utriusque Militiae rank of Gerontius.

One of my more important pieces did not discuss a technical aspect of Arthurian research or, indeed, any new finding, but rather the motivations behind such research:

In that post, I basically admitted to being just as guilty as everyone else when it came to placing my own ego before the requirements of academic objectivity and personal integrity. The twin pillars that lead to perdition in the field of Arthurian Studies are these: desperately wanting/needing to be the "discoverer" of the real Arthur and wanting/needing to accomplish that by conjuring a (hopefully) unique valid historical candidate. I emphasize the word 'unique' in that context because it is only by finding someone new to convert into Arthur that we can come across as the sole revealer of the Truth. The desire for some of us to accomplish this can be so strong that it takes us down a very unhealthy and often unpleasant road. It is this desire which lies at the root of dogmatic views and even fanaticism. Eventually, we become so fixed on our quest and so possessive of our Holy Grail - i.e. so inflexible in our thinking and so committed to our pre-conceived beliefs - that we will forsake all ability at rational argument and even go so far as to reject verifiable evidence and consensus of expert opinion. Methodology and character attacks and, ultimately, full-blown cognitive dysfunction become our last lines of defense in the face of better counter-theories. All along we puff ourselves up with self-importance, seeing in ourselves the righteous guardians of the sacred Secret. The rest of the world is, so far as we are concerned, composed entirely of ignorant or outright hostile and potentially destructive people. We become paranoid in defense of our thesis. The wilder and crazier the belief, the more profound the attending, gnawing doubt.

When I pause to consider all that, I tend to feel somewhat ashamed of myself. For I have, from time to time, engaged in all of it, to one degree or another. Although, to be perfectly honest, I have striven mightily to submit all my own work to critical self-examination (some might say self-immolation!) and have actually abandoned a handful of theories which after significant development had seemed especially promising. I do try very hard not to become too enamored with any of my ideas and am more than willing to revise them or discard them as new evidence or superior logical deduction demands. This kind of behavior has subjected me to accusations of being indecisive or "wishy-washy". One reader who purchased a book complained that every time he turned around there was a new book out by me presenting an entirely different historical Arthur candidate. To placate him, I sent him a free copy of the latest volume.

Now, what possible bearing do the principles expressed in that philosophical aside have on the Uther Pendragon = MVM theory?

Simply put, regardless of how we feel about the pseudo-history of Geoffrey of Monmouth, are we justified in creating Arthurian theory that runs counter to the extant tradition placing Arthur firmly in Southwestern England? I mean, as we have nothing else extant (and, no, I am not including in this statement information on Arthurs subsequent to the son of Uther), for what reason can we categorically state that Arthur should be removed from his strong associations with Devon, Somerset and Cornwall? Given that the only genealogical trace we have for him ties him to the Dumnonian royal house, how can we legitimately substitute for that lineage an imaginatively reconstructed or manufactured pedigree?

For those reasons, I believe we must allow the 'MVM' theory to remain in the game. In the end, it may turn out to be the most valid of any notion I have put forward to help pin down a historical Arthur.

NOTE on the Arthurian name:

We Arthurian researchers also get all caught up in the name Arthur. I myself have sought to use its Roman/Latin origin (Artorius) to prove a connction to various sites in Britain. The problem with this approach is that, well, Arthur is just a name. As such, we cannot possibly know why it might show up in this or that locale in Dark Age England, Wales or Scotland. There are a fair number of Roman names that crop up in the early Welsh genealogies and no one bothers to ask how these names ended up where they're found. Artorius was, in the words of Professor Roger Tomlin, "quite a common nomen." We need not restrict its first occurence in Britain to the second century officer L. Artorius Castus merely because his memorial stone in Croatia is our only extant record of an Artorii in Britain. Nor must we accept that the name could only have been remembered and handed down through the generations among people who knew of Castus, viz. Dalmatians who had served in Roman Britain in the late period, or a ruling family at York. The idea that his name was preserved among the Sarmatian veterans at Ribchester is not possible, as Castus served in Britain prior to the arrival there of the transported Sarmatian troops.

If Arthur had born another Roman name, and that name was otherwise unattested in the British record, we would simply accept it for what it was. Instead, because we have a second century Artorius in Britain, we ASSUME the 6th century name Arthur must derive from that. This is faulty logic.

Thus, we must stop trying to use the Artorius etymology to situate Arthur in the landscape.

Unless, of course, L. Artorius Castus really did take legionary troops to fight in Armorica. The later kingdom of Domnonee was in Armorica, and there is reason to believe that Dumnonia in Cornwall and Domnonee in Brittany may once have been, essentially, one kingdom, ruled over by a single king or related chieftains. As stated in CELTIC CULTURE: A HISTORICAL ENCYCLOPEDIA (p. 606):

"Domnonia was probably settled, at least in part, from

insular Dumnonia (see Breton migrations). It is

likely that British and Armorican Dumnonia functioned

at times as a single sea-divided sub-Roman

civitas and then as an early medieval kingdom."

Had Castus and his British troops fought successfully in the region that became Domnonee in Brittany, his name may have been remembered in the hero tales of the Dark Age Dumnonian kingdom and used for a royal son of the 6th century.

To read some of my old articles on the subject, please see the following blog post links: