Wednesday, June 29, 2022

Mockup for cover of my soon-to-be-published (and last) book.

Tuesday, June 28, 2022

Monday, June 27, 2022

BIRDOSWALD/BANNA, 'THE [FORT OF THE] DRACO OF AELIUS': NEW SCHOLARY OPINION ON THE READING OF THE ILAM PAN

Rollout of the Ilam Pan Inscription

Some of my readers may remember my analysis of the Ilam or Staffordshire Moor Pan a few years ago (https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2019/07/aelius-draco-dacian-and-bannabirdoswald.html).

In brief, I had suggested that perhaps the AELI DRACONIS of the pan's inscription stood for the Aelian Draco, a reference to the Dacian military unit serving at Birdoswald, the Cohors I Aelia Dacorum. Having discussed it with some of the world's best Roman military historicans and Latin epigraphers, I decided to abandon the idea in favor of the conventional views, i.e. the AEL either refers back to vallum as an otherwise unrecorded name for Hadrian's Wall, with DRACO left as a personal name, or Aelius Draco was the personal name in question. One scholar even found a decent candidate for an Aelius Draco, although Roger Tomlin was quick to add "The name 'Aelius Draco' is not very distinctive: there must have been dozens of auxiliary veterans called that."

I had promised myself, however, to return to the problem someday. Having just announced that the time had come to do just that (https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2022/06/a-question-from-fan-why-did-i-abandon_24.html), I made a fateful decision: to write with my earlier query to the scholars who had worked on the pan and who have produced the definitive studies of the object. The academics in question are the highly respected Professor David Breeze and Dr. Christof Fluegel. Their articles are:

Flügel, C. & Breeze, D.J., Drawing the line: a military surveyor on Hadrian's Wall?: Bericht der Bayerischen Bodendenkmalpflege 62 2021 pp.155-170

The Ilam Pan. An alternative explanation for the omission of Aballava (Burgh-by-

Sands) David J. Breeze, Christof Flügel and Erik P. Graafstal

(new paper submitted to the Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society)

Their reaction was interesting. First, they wrote:

"...having discussed your interesting proposal with David Breeze, we think, that interpreting Aeli Draconis as sort of a poetic allusion to Banna is not possible, although strictly grammatically (but not archaeologically) spoken „(castra) Aeli Draconis“ (the fort of the Draco of Aelius) could fit your proposal."

This seemed like a good start, but they quickly followed that up with an objection based on chronology:

"The Ilam Pan, according to the main specialist in the field of Roman bronze vessels, Richard Petrovszky, on the basis of the cast construction technique, dates some decades before 150 AD, as provincial vessels starting shortly before or around 150 AD are always made of bronze sheet. In the 2012 publication on enamelled bronze vessels all authors agreed that the Ilam Pan is the earliest in the whole series. A (poetic) refence to Banna in the inscription is therefore simply contradictory to the dating of the vessel itself, as the name „Aelia“ of the Cohors Dacorum only appears from 146 AD onwards."

As it happens, the 146 AD date for the Aelia honorific as it was applied to the Cohors Dacorum is incorrect. I had found that Paul Holder claimed (http://www.uni-koeln.de/phil-fak/ifa/zpe/downloads/1998/122pdf/122253.pdf) Aelia was granted to the unit in 127 AD (for the diploma in question, see http://www.uni-koeln.de/phil-fak/ifa/zpe/downloads/1998/122pdf/122253.pdf).

To quote from Holder's article:

"Raised in Dacia, this cohort is first attested with its honorific title on a diploma for Britain of 20th

August AD 127 as cohors I Ael(ia) Dac(orum) (milliaria).17 This evidence invalidates earlier

discussions of the origin of the unit.18 The diploma shows that the men discharged then would have

been recruited in AD 102 or a little earlier. There are a number of possible explanations for this. The

date might represent when the cohort was raised by Trajan from Dacians settled within the Empire. The

award by Hadrian would then have been a battle honour. The only opportunity for gaining such an

award would have been on the Lower Danube early in Hadrian’s reign if, indeed, the trouble was

serious enough. Alternatively the unit was raised by Hadrian early in his reign, hence the honorific title,

and those men discharged in AD 127 were part of the cadre around which the unit was formed. It is also

conceivable that, in origin, it was a numerus Dacorum raised by Trajan which was converted to a cohort

by Hadrian. (This question will be looked at in more detail below.)

By the third century AD it formed the garrison of Birdoswald on Hadrian’s Wall where it is attested

on a number of inscriptions. The earliest recorded date is the governorship of Alfenus Senecio, AD

205/8, from a building dedication (RIB 1909). It was still there when the Notitia Dignitatum was drawn

up (Not. Dig. Occ. XL,44).

On the diplomas for Britain of AD 145/6 (RIB 2401.10) and AD 158 (P. A. Holder, op. cit., (n. 13)

it is called cohors I Aelia Dacorum without any indication of size."

When I asked Roger Tomlin for confirmation of this, he replied:

"Holder is right, and I would think the other sources belong to a date before the Bulgarian diploma was found, when the earliest attestation of Aelia was in the diploma of 145/6 (CIL xvi 93). The Bulgarian diploma, as I call it, links up with the leaf published by Holder in ZPE 117. They are now Roxan and Holder, Roman Military Diplomas IV, No. 240, and the date is undoubtedly 20 August 127, when the cohort has the title Aelia.

Some inscriptions from Britain do not give it the title – for lack of space? – such as RIB 1365 from the Vallum. Before RMD IV, 240 was found, this prompted some to think that it gained the title later than Hadrian, from Antoninus Pius."

What this means, I feel, is that the Ilam Pan inscription may actually COMMEMORATE the posting of the Cohors I Aelia Dacorum to the Banna fort. According to English Heritage (https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/birdoswald-roman-fort-hadrians-wall/history-and-stories/history/), "Birdoswald’s history began when a wooded spur was cleared for the building of Hadrian’s Wall in AD 122. The fort, added to the Wall shortly afterwards..." It makes sense to propose, then, that once the fort was completed, the Dacians were assigned to it. The Ilam Pan would have been fashioned at this time.

The only drawback to this theory concerns the nature of the Dacian milliaria: it was an infantry unit, not cavalry. The draco standard was a cavalry emblem. Dr. Fluegel discussed the problem thusly:

"A Cohors Dacorum would not have had a Draco Standard but a simple vexillum: Draco standards, as known from the famous specimen of Niederbieber (Germany), were exclusively used during in cavalry competitions on the parade ground. It is true that for example in Trajan`s column draco standards are used to identify Dacian enemy units, but this is not true anymore for a Cohors Dacorum in Roman times (which was an infantry unit and therefore would not have used an standard used in equestrian games)."

He is not entirely correct about this.

Robert Vermaat (http://www.fectio.org.uk/articles/draco.htm) discussed the Roman infantry's use of the draco:

"It is not documented when exactly the draco was adopted as a normal standard for all troop types. However, sources mention the draco being used with the infantry. The Historia Augusta mentions that the mother of Severus (193-211 AD) dreamt of a purple snake before his birth, something very alike what we later hear of the Imperial standard[3]. But since this source was probably compiled later, we can't be sure this has any bearing on a dating. We are on more solid ground with the entry of the reign of Gallienus (253-268 AD), when legionary troops are said to have paraded with a dracon amongst the standards of the legions[4] and the troops of Aurelianus (270-5 AD) also had draconarii amongst the standard-bearers[5]. This may lead us to conclude that the infantry began using dracos during the late 3rd c. On the Arch of Galerius, which was built before 311 AD to commemorate Galerius' war against Persia in 290 AD, several dracos can be seen to his left and right, carried by infantry as well as cavalry."

J.C.N. Coulston (Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies 2 1991 The ‘draco' standard):

"On Julian's acclamation a draconarius of the infantry Petulantes supplied his torquis as a diadem...

Copper alloy box panels from Ságvár (Hungary), dating to the 4th century, provide the last depictions of Roman dracones (Fig. 11).32 The scale is too small and the detail too slight to give a clear indication of the draco type, but, most importantly, the dracones are carried by infantry as well as cavalry...

Through the 2nd and most of the 3rd centuries, 'dracones' were seemingly confined to cavalry, but they spread to legionary and other infantry possibly in the later 3rd, and certainly by the 4th century. In addition, dracones were employed as the personal standards of emperors during the 4th century...

The key to understanding the use of infantry dracones may lie in Vegetius' assignment of one draco to each legionary cohors. This seems to be the first reference to a single, overall cohort standard. Traditionally there were none between the levels of centurial or manipular signa and legionary aquila.61 This is a curious absence if the cohors was the tactical unit in the Principate legio, and auxiliary units had their own cohors level standards.62 Perhaps the increasing tendency in the 3rd century to detach cohortes from parent legiones played a part in draco provision."

Now, admittedly, the evidence such as we have it indicates that infantry would have the draco only well after the time of the Ilam Pan and the establishment of the Dacian garrison at Birdoswald. However, we must bear in mind that we are talking about Dacians here. So far as we know, they were the originators of the draco. I don't think it's stretching credibility to allow the Birdoswald Dacians to have venerated their draco in the early period. I would once again point to RIB 1904 (https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1904), which is a dedication to the standards of the unit.

NOTE:

Does the notion of Birdoswald/Banna being the Fort of the Draco have any bearing on my Arthurian research?

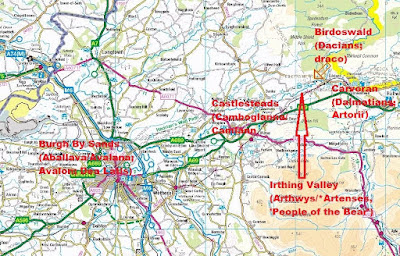

Well, if we are to allow Arthur's father, Uther Pendragon, to be linked to the draco standard (independently of Geoffrey of Monmouth; see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2022/06/why-supposed-connection-between-uther.html), then we must pay attention to Birdoswald. Not only does Birdoswald show a Dark Age reoccupation of the Roman fort, but it lies in the Irthing Valley. This river-name probably derives from the Cumbric word for 'bear', and I have placed the *Artenses or 'Bear-people' there (the tribal designation is preserved in the Welsh eponym Arthwys).

Furthermore, Carvoran Roman fort is only several kilometers to the east of Birdoswald. The former was garrisoned by a Dalmatian unit. We have an inscription there recording the death of a woman from Salona. I have identified this fort, as well as York and its Praesidium (itself manned by another Dalmatian unit), as a primary candidate for an ethnic group that may have preserved/passed along the Roman/Latin name Artorius among its descendents. As far as Carvoran is concerned, the Artorii are known to have been present at Salona, and L. Artorius Castus was himself probably born in Liburnia. Certainly, he served as procurator in that province, and was buried there.

I would add that my identification of the Arthurian battle sites fits in very well with an Arthur towards the center of Hadrian's Wall. In addition, Camboglanna/Castlesteads, just to the west of Birdoswald and also in the Irthing Valley, is the best possibility for Arthur's Camlann. Lastly, his 'Avalon' may well be a reflection of the Aballava/Avalana 'apple-orchard' Roman fort at Burgh-by-Sands, not far to the west Castlesteads.

Another emblem of the Dacians found used by the unit posted at Birdoswald is the falx. From

J. C. Coulston, B.Sc., M.Phil., Archaeologia Aeli-ana 5th Series, Vol. 9, 1981:

“A Sculptured Dacian Falx from Birdoswald

The inscribed stone in question, R.I.B. 1914, was found in 1852 outside the wall of the south guard-chamber of the main east gate of Birdos-wald fort. It was set up under Modius Julius, governor o f Britannia Inferior in a. d. 219, by the cohors I Aelia Dacorum commanded by M. Claudius Menander. This regiment can hardly have been raised before Trajan’s Dacian Wars and was a regular unit by c. 130, when it was helping in construction work on the Vallum (1365). Under Hadrian it may have been sta-tioned at Bewcastle and by a. d. 205-8 it was at Birdoswald building a granary (R.I.B. 1909). The inscription is flanked on the dexter side by a palm branch and on the sinister side by a curved sword. The latter represents a falx of the single-handed type, with pommel and guard. This weapon was characteristically carried by Daci-ans, as depicted in sculpture and coins and oc-curring amongst small finds. This representation on a stone set up by a cohors Dacorum makes the identification almost certain. On the spiral frieze o f Trajan’s Column several Dacians are shown using with one hand, notably in Cichori-us Scenes LX V II, L X X II, X C V -X C V I, C X L V and C L I. The melee around Roman defence-works in Scenes X C V -X C V I includes no few-er than seven in action. These falces have either a long handle, as in Scene L X II, or a shorter handle with a long curving blade and guard ap-proximating to the Birdoswald example. Corrob-orative representations are seen on the Adamk-lissr congeries armorum frieze and on a denarius of Trajan; both examples have guard and pom-mel. One actual falx, 55 cm long, has been found at Kaloz in Rumania. Another, from Gradistea Muncelului, is 68 cm with a tapering tang. The double-handed falx was much longer. An exam-ple from Rupea (Cohalme) in Transylvania is 90 cm long, with a metal haft for just over half its length. The latter would have had a wooden sheathing, balancing the wicked curved blade which gives the weapon its name. The Adamk-lissi metopes depict these falces in use against Roman legionarii equipped with ocreae and manicae to protect their limbs. According to Ar-rian the Greek kopis, a single-handed sword not unlike the one-handed falx, was capable o f shearing off a man’s arm and shoulder with one blow. In the Metopes all the Dacians have falces, their Germanic allies being equipped with shields and javelins. Vulpe used this contrast with the depictions of Dacians on Trajan’s Col-umn to argue for an invasion of Moesia Inferior by Sarmatae, Buri and Eastern Dacians, unat-tested in the literary sources. The pedestal of the Column may, however, depict a large falx to the left of the doorway. In its double-handed form the falx often occurs when Dacian spoils are de-picted. Four Trajanic coin issues show the curv-ing blade and Scene LXXVIII on the Column may include them. A ferculum relief in the Museo delle Terme, Rome, and an unpublished relief in the Split Archaeological Museum, Yugoslavia, both have a falx with other weapons. The identi-fication o f the falx with the Sarmatian double-handed swords of Tacitus is not unreasonable. The small falx on the Birdoswald stone is repeat-ed on R.I.B. 1909, though there the palm branch and sword are transposed. In this example the handle is badly worn but the curve o f the blade shows clearly. The Birdoswald falces may indi-cate a unique regimental badge or the carrying of falces, instead of spathae, by the Dacian auxil-iarii. A jealously guarded regimental tradition such as is suggested would have a close modern parallel in the Gurkha soldiers with their kukris. A tentative comparison might be made with the ethnic dress o f the Chester ‘Sarmatian’; and, ac-cording to Hyginus, irregular Dacian units were used in the later second century. The use of fal-ces therefore bears consideration. It is certainly unusual for an auxiliary cohors to depict a regi-mental weapon or badge in sculpture.”

If the Dacians at Birdoswald were going to con-tinue to use their falx, either as an actual weap-on or at the very least as a regimental emblem for centuries, is it unreasonable to suppose they ascribed similar importance to their draco?

Sunday, June 26, 2022

COMING SOON: An Announcement of New Scholarly Opinion Concerning My Reading of 'AELI DRACONIS' on the Ilam Pan

Staffordshire or Ilam Pan

A few years ago I very tentatively suggested that the AELI DRACONIS on the Ilam Pan should be read

differently than the conventional translations. Rather than see AELI has an otherwise unrecorded name for Hadrian's Wall, with Draconis for a personal name or, alternately, Aelius Draco as a personal name, I wondered why it could not be a reference to the Aelian draco at the Dacian-garrisoned Banna Roman fort. AELI DRACONIS stands in place of Banna on the pan in the listing of forts from west to east. We have Banna recorded on two similar objects following the same line of the Wall.

Over the past few weeks I revisited the idea with Professor David Breeze and Dr. Christof Fluegel, authors of the definitive studies on the Ilam Pan.

Their conclusion?

Please stay tuned for that and more in my next blog post.

Saturday, June 25, 2022

Lucius Artorius Castus: No Sarmatian Connection

Some time ago, my colleague Antonio Trinchese informed me that his work on the Lucius Artorius Castus memorial stone had revealed that the 'Procurator Centenarius' formula could not be found prior to the Severan period. After some additional digging, I was able to extend that back to the reign of Commodus (c. 190). While we know this pay grade was applied to procurators well before Commodus' time, and we have several stones discussing pay grades of various ranks from the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the actual formula used on the LAC stone is not extant for the earlier period.

This would seem to create a problem for us. For the only known (that is, historically attested) reorganization of Dalmatia occurred c. 168 (see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2021/02/the-date-of-lucius-artorius-castuss.html). I had made the case for this being the time of the appointment of LAC to the Liburnian procuratorship and the formation of that new provincial division. I have yet to find a professional Roman military historian who does not hold to the view that the most probable date for the founding of Liburnia was just prior to 170. Yet if LAC began as procurator in 168, or at least prior to 170, we are left with a two-decade long span before we encounter another such stone with the procurator centenarius formula.

Antonio (along with Dr. Linda Malcor and Alessandro Faggiani) would have us believe this 20 years is an insuperable gap. Their conclusion, therefore, is that he must have become procurator around or after 190. Their own preference is during the Severan period.

What it comes down to this this: how long might a procurator have served, especially as it was the last rank LAC held in his career? To this we might add the obvious: although LAC claims on his stone to still be alive when it was fashioned, he may well have been retired for some time and even elderly or close to the end of his life. The carving of the stone thus could be placed at a time when the new pay grade formula had just come into fashion. It is not impossible, of course, that the LAC stone displays the first known occurrence of this formula. This is especially true if LAC were indeed made the first procurator of a newly established province in Dalmatia.

So what are we looking at for the term lengths of provincial procurators?

As it turns out, they could serve however long they wished to, subject only to the Emperor's pleasure. The best summary of this fact can be found in this recent, authoritative title:

In that source we are told that "In a procuratorial province, the governor or procurator was appointed directly by the emperor and could serve any length of time he desired."

The infamous Potius Pilate, for example, was procurator of Judaea for 10 years. While I've not yet made a search for other procuratorships lasting this long or longer, I have no doubt that such exist. When and if I have the time, I will attempt to compile a list of such. The more we find, and the longer the terms of those procuratorships prove to be, the more we can allow for the extension of LAC's Liburnian procuratorship.

Given all of the above, I don't think we can afford to insist on LAC being made procurator sometime after 190 A.D. Instead, we may dovetail him quite nicely as a new procurator c. 168, when Dalmatia was reorganized by the joint emperors in the face of the Marcomannic Wars. This being the case, we can have LAC attend Statius Priscus from Britain to Armenia, and accept a reading of ARM[ENIO]S (with a simple N-I ligature) on the LAC stone. We also can let go of the idea that LAC had anything whatsoever to do with the Sarmatians in Britain, who were not shipped there by Marcus until 175 A.D.

If you have LAC commissioned directly into the centurionate (something Tomlin has assured me is quite possible), and allow him to be in his mid-40s, rather than mid-50s, when he goes to Armenia in the early 160s, and then have him made procurator of Liburnia c. 168, he would then be around 50. Let him serve a decade or so (the Marcommanic Wars ended in 182), then retire. He may have made his stone anytime during the reign of Commodus, which is when the procurator centenarius formula first shows up. In 180 (when Commodus started ruling on his own), LAC would be in his early 70s. In 190, his early 80s. There is nothing far-fetched or unrealistic about this - even if we allow for LAC having retired prior to the end of the Marcomannic Wars. He still could have lived in retirement for enough years to take him to the time of Commodus and to have then carved his memorial stone.

Tomlin has pointed out to me that some soldiers' careers could be very long indeed. He cites Pflaum for Cn. Marcius Rustius Rufinus, who became centurion in the reign of Marcus, and proceeded through a series of posts like those held by LAC to become Severus' praefectus vigilum in c.207, enjoying a 30-year career.

As there is some reason to think LAC was the only procurator of Liburnia, it is possible that particular administrative entity - formed because of the onset the the Marcomannic Wars - ceased to exist at the completion of those wars. That event may have coincided with LAC's retirement.

When LAC was made procurator c. 168, he was paid 100,000 sesterces a year. Or maybe that was his final pay grade in the last year he served as procurator. Doesn't really matter which. We know this pay grade was given to procurators even before the time of Marcus. As well as pay grades even higher. Then, late in his life, after retirement, when the formula proc c is current in the reign of Commodus, that is how he carves his rank on his stone. I have gone on and on and on about pay grade/rank inscriptions from the time of Marcus, like that of Marcus Valerius Maximianus. The pay for the rank is NOT THE ISSUE. It is the formula for the rank, proc c, which seems to have originated under Commodus.

Marcus Valerius Maximianus is paid 100,000 sesterces for leading cavalry, then is made procurator of Lower Moesia WITH INCREASED salary. He did all that BEFORE he was made a senator. See http://www.rimskelegie.olw.cz/pages/articles/legincz/mvaleriusmaximianus_en.html.

ARMENIOS remains the best possibility for the ARM[...]S of the LAC stone. At least, this is the consensus of all leading Roman epigraphers. ARMORICOS (with R-I and C-O ligatures) does fit the stone, and would imply a date concurrent with the Deserters' War/Maternus Revolt under Commodus. Unfortunately, we have no independent record of a campaign to Armorica. And such a late date does not accord with the reorganization of Dalmatia c. 168. ARMATOS, still the preferred reading of Trinchese, Malcor and Faggiani, has to my knowledge not been accepted by anyone other than the publisher of their journal article on the subject. Every top Roman epigripher and Roman military historian I have consulted reject the proposed reading. In any case, even if we do opt for LAC fighting 'armed men' (Tomlin's phrase comes to mind here: "a Roman general wouldn't have congratulated himself on fighting against 'armed men', any more than he would have recorded a campaign against inermes."), we find ourselves with a phrase which does not allow us to identify the military action in question with any known event recorded in extant sources. Not, that is, without availing ourselves of unbridled and totally unsupported speculation.

My conclusion, then, after many months of soul-searching, is that LAC took legionary vexillations with him to Armenia under the British governor Statius Priscus. Not too long after the successful Armenian campaign, LAC was awarded the Liburnian procuratorship. He held the position for a considerable period of time before retiring and then had his memorial stone constructed sometime around 182-190, i.e. during Commodus's reign.

My arguments can be set forth in simplified form as follows:

1) The Roman governor Statius Priscus, in the early 160s, was sent from Britain to Armenia on an emergency status. He may well have taken some legionary vexillations with him. LAC may have commanded those units. ARMENIOS is the best reading for ARM[...]S on the LAC memorial stone.

2) Liburnia was probably formed shortly before 170. This would have been when LAC was made procurator of the new province.

3) LAC may have remained procurator of Liburnia for quite some time. He may well have made his stone after retirement, and even when he was quite old. This allows us to accept the "formula" of procurator centenarius as belonging to the right period, i.e. during the last several years of the reign of Commodus.

What follows is a listing of the more important articles I have written on LAC. Taken together, they provide more than ample evidence in support of the ARMENIOS reading for the memorial stone. And if ARMENIOS is correct, then LAC was in Britain prior to the arrival of there of the Sarmatians, and thus would not have had anything to do with the Sarmatians in Britain.

WHY ANY DIRECT CONNECTION BETWEEN UTHER PENDRAGON AND THE DRACO STANDARD MUST BE PERMANENTLY REJECTED

Dacians with a Draco Standard on Trajan's Column

This statement has been a long time coming - even from me, a person who tends to be more skeptical than most: we need to divest ourselves of the false notion that Pendragon as an epithet should be related directly to the draco standard.

Over the last few years, when delving more deeply into the career of the 2nd century Roman officer L. Artorius Castus, I have gotten bogged down time and time again in chasing the dragon's tail. Uther's supposed connection with the draco is a romantic fiction we readily accept. But trying to link Arthur's father and his dragon to Geoffrey's draco, we continue to delude ourselves. It is well known that the word dragon in pre-Galfridian literature was merely one of several animal metaphors employed by poets for warriors and/or chieftains.

The top Welsh specialists are all in agreement in this assessment of the proper use of the word dragon in heroic poetry. While John T. Koch (CELTIC CULTURE: A HISTORICAL ENCYCLOPEDIA) leaves open the slight possibility that Geoffrey of Monmouth's interpretation of Pendragon may be correct, in balance he does not think so:

For Geoffrey, the epithet Pendragon is ‘dragon’s head’,

an explanation of a celestial wonder by Merlin (see

Myrddin). This meaning is not impossible, but since

Welsh draig, pl. dragon < Latin drac}, dracones could also

mean ‘chieftain, military leader, hero’ (see draig goch;

dragons), Pendragon could be ‘chief of chieftains’.

Rachel Bromwich in her TRIADS is less forgiving:

Even Sir Ifor Williams (in his notes to THE POEMS OF TALIESIN) provides this definition for

dragon: 'a dragon, (fig.) fighter, champion, leader, chieftain.'

A.O.H. Jarmon (his his THE GODODDIN) has for dragon, 'ruler, prince', and for draig, 'chieftain, prince.'

Etc.

Even less weight should be given to Geoffrey's interpretation once we realize even his dragon star was an imaginary motif. He got it from a line of the MARWNAT VTHYR PEN, which reads 'I am like a cannwyll in the gloom.' Cannwyll means 'candle', but figuratively meant 'star, sun, moon, luminary, leader' and the like. Its metaphorical use in this context is proven by a matching phrase a few lines prior: 'I am a leader in the darkness.'

Thus what Geoffrey did was to take cannwyll for star, and convert that into a star that stood for Uther himself. He then cleverly extrapolated from Uther's epithet a dragon's head, and used that to describe the star. From there it was an easy step for him to link the dragon head star to a draco standard. The process may seem far-fetched to some, but this is just one instance of an endless series of manufactured events in his masterful pseudo-history. Too many Arthurian scholars underestimate Geoffrey's resourcefulness, adaptive abilities and pure inventive genius. At their own peril, they forget that there is nothing of true history in his pages.

My advice to burgeoning Arthurian researchers is two-fold: 1) utterly adjure Geoffrey of Monmouth's work and 2) ignore any theory which adheres to Geoffrey's notion that Uther was named for the dragon head star and became distinguished for carrying around the draco.

Now, as a caveat I would add this: the dragon itself, employed as a metaphor for a warrior and the like in Welsh poetry, may have originated any number of ways. In the case of Uther, supposed brother of Ambrosius/Emrys, we must bear in mind that the two dragons of Dinas Emrys (= Caer Dathal; see https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2021/01/dinas-emrys-as-caer-dathal-late.html) are more likely models for the draco in Geoffrey, and we may be able to tentatively associate the former creatures with the crossed serpent insignia of the Roman military unit serving at Segontium.

I have pointed out before that Geoffrey's comet, while it is said to signify Uther, would in traditional medieval lore would instead have appeared to mark the death of Ambrosius. Geoffrey had already made much of the two dragons of Dinas Emrys, going so far as to fuse the northern Myrddin/Merlin with Ambrosius. We must remember that Uther HAS TWO DRAGONS FASHIONED after the image of the dragon comet. Why two? Because they were reflections of the dragons of Dinas Emrys, of course.

One of the dragon standards is left at Winchester, while Uther carries the other with him in his wars. We should not forget that Winchester was for the early period the Saxon capital, and Wessex itself had a dragon standard. The white dragon of Dinas Emrys, after all, represented the English invaders.

Finally, the Roman military unit stationed at Segontium not far from Dinas Emrys is known to have been sent to Illyricum. The Dalmatia of the Artorii and, in particular, L. Artorius Castus, was a part of Illyricum. It is quite possible that some soldiers retiring from the unit may have returned home to Britain. They may well have brought the story of LAC with them or, at the very least, the name Artorius - the later Arthur.

That Uther's dragons should be traced to the Dinas Emrys dragons rather than to a draco standard may be proven definitively by some lines from the Welsh "Gwarchan Maeldderw." I have the authoritative edition by G. R. Isaac, published in CAMBRIAN MEDIVAL CELTIC STUDIES 44 (Winter 2002). The relevant section reads:

"...in the presence of the spoils of the Pharaoh's red dragon,

companions (will?) depart in the breeze."

As Isaac explains in the notes -

<pharaon sb. m. 'Pharaoh'

I am interpreting the syntax as a poetic transformation of what would normally be expressed in the word order (also modernizing the orthography) ar fudd draig rudd Ffaraon. As Williams notes, the mention of the 'red dragon of Pharaoh' is suggestive of a reference to the story of the dragons of Dinas Emrys in Nant Gwynant, Snowdonia, as told in Historia Brittonum and Cyfranc Lludd a Llefelys.>

The Pharaoh in question is, of course, Vortigern, who is called thus in Gildas.

Friday, June 24, 2022

URIEN OF RHEGED AS UTHER PENDRAGON: WAS THE GREAT ARTHUR TEMPORALLY DISPLACED ?

Lochmaben Stone

"From then on victory went now to our countrymen, now to their enemies... this lasted right up to the siege of Badon Hill..." - Gildas

"The Battle of Badon, in which Arthur carried the Cross of our Lord Jesus Christ for three days and nights on his shoulders and the Britons were the victors." - Welsh Annals

"During that time, sometimes the enemy, sometimes the Cymry were victorious, and Urien blockaded them for three days and three nights in the island of Lindisfarne." - Nennius

***

Years ago, I flirted around with the idea that Arthur should be linked to the great Urien of the North. I dispensed with the idea for one and only one reason - and it was a very good one: Arthur could not be a son of Urien because of chronology. The lord of Rheged was simply too late for us to allow him to be Arthur's father or for Arthur to be his contemporary.

But as I recently promised to take yet another look at a possible Arthur of the North (https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2022/06/a-question-from-fan-why-did-i-abandon.html), my reevaluation quickly turned towards Urien. Why?

Well, it began, yet again, with consideration of the gorlassar epithet as it is applied to Uther in his elegy poem, MARWNAT VTHYR PEN. Marged Haycock, in her notes to the poem, has the following:

gorlassar Cf. PT V.28 Gorgoryawc gorlassawc gorlassar, rhyming with escar,

as here; again PT VIII.17 goryawc gorlassawc gorlassar. Both passages are

corrupt. PT 98 suggests ‘clad in blue-grey armour’ or ‘armed with blue-grey

weapons’, following G and GPC who derive it from glassar ‘sward, turf, sod’

rather than llassar ‘azure’, etc. (see GPC s.v. llasar), presumably because one

would expect *gorllasar. That may indeed have been present, with l representing

developed [ɬ]. Llassar is rhymed with casnar, Casnar (cf. line 10 casnur) in CBT

III 16.55, VII 52.14-5. On the personal names Llasar Llaes Gygnwyd, OIr

Lasa(i)r, calch llassar ‘lime of azure’, etc., see Patrick Sims-Williams, The Iron

House in Ireland, H. M. Chadwick Memorial Lecture 16 (Cambridge 2005), 11-

16; IIMWL 250-7.

I had noted early on that gorlassar is found in only one other context: it is attached to Urien of Rheged in the Taliesin poetry.

Doing a search on my own blog site, I picked out several articles I had written on possible connections between Uther and Urien. One of the most important can be found here:

That piece explored in depth Urien and his son Owain's special relationship with the god Mabon. Rheged, of course, had its heartland in exactly the region where Maponus had his chief shrine (https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/09/the-nucleus-of-uriens-kingdom-of-rheged.html). Mabon, in the PA GUR, is said to be the servant of Uther Pendragon.

Dragon titles belonging to Urien and Owain (and.or Mabon) are extant in the poetry: Udd Dragonawl or 'Lord of Dragon(s), Dragon-like Lord' for the father, and Rwyf Dragon or 'Leader or Dragon(s) for the son. The Oruchel Wledig title for Urien was uncannily like Uther Pendragon.

I even dared to think about the possibility that Uther Pen may, in part, have been derived from the decapitated head of Urien, which plays a major role in the Llywarch Hen poetry (https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/11/the-text-of-pen-urien-from-canu.html; https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/11/urien-pen-and-dragon-repost-of-udd.html).

Finally, time and time again I have striven to account for why both Urien and Arthur were said to have fought at Bremenium/High Rochester (Breguoin or Agned, the latter from Egnatius, the Roman governor who rebuilt the fort). I offered that either the Brewyn battle was stolen from the Urien poetry by the author of the Arthurian battle list in Nennius, or that both men had fought at the site at different times. That both men may have fought there at the same time was not a notion I was willing to entertain.

So here is the dilemma I currently find myself in: as I am quite content with my various proofs that demonstrate quite well that the famous Ambrosius Aurelianus did not belong to the 5th century, but instead to the 4th, why am I sticking so stubbornly to the generally accepted Arthurian dates? In the Welsh sources, we are told Arthur fought Badon c. 516 and died at Camlann c. 537. The narrative in Nennius brackets the Arthurian battles precisely during the floruit of Cerdic of Wessex, as that chieftain's career is detailed in the ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLE. With dating that seems so precise, how can we justify putting our hero during the reign of Urien (b. c. 510, d. c. 585/586; P.C. Bartrum)?

Let's begin trying to answer this question by looking at the subsequent Arthurs of the Dark Ages.

1) According to Bannerman (STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF DALRIADA), Artur son of Aedan died c.590. The Irish Annals say 596.

2) Bartrum gives for an approximate birthdate for Arthur son of Pedr of Dyfed 560 A.D. I made the case for this man being the Arthur son of Bicoir the Britain of the Irish Annals, which have him kill the Irish King Mongan in 625. [Bicoir is merely a slight corruption of Petuir, one of the forms for Pedr in the Irish souces.] Thus it is likely Bartrum is somewhat off and Arthur son of Pedr's birthdate should be moved up to the latter part of the 6th century or the very beginning of the 7th.

3) In a corrupt Welsh TRIAD, which I also have discussed at length in various blog posts, an Arthur Penuchel 'Overlord' is given as the son of Eliffer of York by a daughter of Cynfarch, father of Urien of Rheged. We know that Eliffer's sons fought at Arderydd (modern Arthuret) in 573 and perished at Caer Greu (modern Carrawburgh on Hadrian's Wall) in 580.

Do any of these dates prevent us from having a more famous Arthur active during the reign of Urien, which terminated c. 585/6?

No, they do not.

But if the famous Arthur of the North, who belonged to the Kingdom of Rheged, belonged to this time period, how can we account for the traditional Welsh dates for him?

Well, it may be that the Welsh, at some point, decided they needed a hero to fill the "gap" between their Ambrosius and Urien himself. If Arthur did not outlive his father Urien, and thus did not inherit the kingdom of Rheged to rule, we would not find the former listed in the royal genealogy. Putting him at the time of Cerdic of Wessex made sense, as he could thus appear to be a sort of counter to Cerdic. Of course, I have uncovered sufficient evidence to suggest that Cerdic was, in fact, Ceredig son of Cunedda, and either he was allied with the Saxons against the Jutes in Hampshire and on Wight, or the conquering English later co-opted an actual champion of the Britons by transforming him into their own founder. My readers know that I have recently proposed Cerdic/Ceredig as Arthur, and even have en entire book out detailing this argument.

If Arthur is to be seen as a prince of Rheged, then the Northern battles as I first identified them may be allowed to stand:

Aballava, Banna and Magnis)

An Arthur buried at Aballava/Avalana (= "Avalon") makes sense in this context as well, for this fort would surely have lain in the home territory of Rheged. I would add that it may also be significant that in Welsh tradition - not the Galfridian - Modred/Moderatus is a son of Lleu son Cynfarch (https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2017/09/arthur-penuchel-and-medraut-son-of-lleu.html), the same Cynfarch who was the father of Urien.

In conclusion, then, should we choose to identify Uther Pendragon/gorlassar with the only other notable figure bearing that epithet, viz. the historical Urien of Rheged?

A QUESTION FROM A "FAN": WHY DID I ABANDON THE NORTHERN ARTHUR?

"Hi, August. Huge fan of yours here. But I've been more than a little disappointed in the direction you've taken in your more recent work. May I politely ask why you so easily abandoned the Northern Arthur? You seemed to have all the sites down perfectly - like I've never seen before - and you had a more than adequate explanation of where Arthur and his father should be placed. I mean, it all worked beautifully, as far as I'm concerned (in my amateurism). Are you sure you are justified in going south (!) just because you can't certainly identify Uther with any known historical person? Is there a way you can save the Northern Arthur?"

Hmm. Wow. Okay. Firstly, I didn't know I had fans out there in the ethereal, arcane Arthurian community. That's kind of nice to know. Over the years, given what that community has, in general, become, I've either alienated many of its members or simply excused myself from the debate. Found it necessary, ultimately, to shield myself from its unbridled rancor, supercilious sensationalism and the kind of rampant naivety only nonspecialists on a mission can engender. But when I'm asked an intelligent question, especially one that makes me sit up and examine my own motives, I tend to pay attention.

Yes, the Northern theory in most respects looks, well, awesome (to use a much overused expression). In essence, I had battles that were identified with precision, both linguistically and geographically.[1] The "pattern" produced by the plotting of these battles on the map revealed an unexpected line of campaigns running north and south in northern England and southern Scotland along the old Roman Dere Street. This looked suspiciously like a frontier zone, a line of division between the encroaching Saxons to the east and the Britons to the west. Finding the battles eleswhere necessitated proposing early manipulation of the place-names, often involving unprovable attempted translations from one language to another.

I also had some remarkable correspondences on Hadrian's Wall. Castlesteads or Camboglanna fit Arthur's Camlann perfectly. Just a few miles to the west along the Wall was Aballava, with its spelling variant Avalana. This 'place of the apple orchard' made for a wonderful Avalon, complete with its own Lady of the Lake in the guise of the Roman period Dea Latis or "Lake Goddess."

Camboglanna and Birdoswald/Banna, the latter with its significant Dark Age hall built in the ruins of the Roman fort, were in the Irthing Valley, a river-name quite probably to be traced to a Cumbric 'bear' word. This was the likely home of the *Artenses or 'Bear-people', whose name is preserved in the Welsh genealogy for the famous Men of the North as Arthwys. Birdoswald had been manned in the late Roman period by Dacians, who are noted for their use of the draco standard. Many authorities hold that it was the Dacians who actually introduced the draco into the Roman army. Lucius Artorius Castus, the 2nd century Roman soldier who served in Britain, had previously served in legions based in or operating in Dacia.

Only a few kilometers to the east of Birdoswald along the Wall is Carvoran, the Roman period Magnis, a fort whose garrison was originally composed of Dalmatians. This is interesting, in that there was a branch of the Artorii at Salona in Dalmatia (modern Croatia) and there is now a consensus that Lucius Artorius Castus himself was probably born there. Certainly, he was awarded with the governship of Liburnia at the end of his military career.

Taking all of this into account, it would be natural to paint the following speculative, though eminently logical picture of the Arthurian context on Hadrian's Wall:

1) Uther Pendragon, if we may allow for him actually having been associated with the Roman draco, hailed from Birdoswald in the Irthing Valley. His epithet Pendragon may originate in the Late Roman rank of magister draconum. Or the leader of Birdoswald was simply called the Terrible Chief-dragon because of the draco standard and its sacredness to the warriors residing there. I am, in fact, still working with Drs. Breeze and Flugel on the possibility that the 'AELI DRACONIS' on the Ilam pan does not involve an Aelian (= Hadrian's) Wall or a man named Aelius Draco, but instead is a poetic reference to the draco-bearing Cohors I Aelia Dacorum of the Banna fort.

2) Arthur was given his name because Artorius (person and/or name) was remembered at the nearby Dalmatian fort at Carvoran. It was interpreted by the Cumbric speakers as containing their own word for bear.

3) Arthur fought the Saxons from the Firth of Forth to Derbyshire, along an established north-south line.

4) Arthur fought Medraut (Moderatus) at Castlesteads/Camboglanna in the Irthing Valley. Legend had it that he was conveyed to Burgh By Sands/'Avalon' for burial. This may be factual or may simply reflect the Celtic fondness for the Otherworld island of apples. Or it may be a combination of both, i.e. Arthur was taken there because this ancient Avalon was still thought of as sacred place.

5) In the HISTORIA BRITTONUM, the story of Arthur is followed immediately by that of St. Patrick. I have shown conclusively that Patrick's birthplace was the Birdoswald/Banna Roman fort on Hadrian's Wall.

[CAUTIONARY NOTE: Time and again I have been warned by top scholars that we must be careful when basing an argument on the principle of CONTINUITY. In other words, it can be difficult to account for the survival of an ethnically derived name or cultural trait over long spans of time. Studies on the garrisons of frontier forts have differed somewhat in their conclusions regarding this principle. The emphasis currently is to favor the tendency for these garrisons, over the centuries, to become much less homogeneous. So even though we find the Dacian falx as a unit emblem on stones from Birdoswald, we cannot automatically assume the unit's special dedication to the draco would have been evidenced in the late period. Similarly, presevation of the name Artorius at Carvoran cannot be proven to have occurred. We can only provisionally put forward the possibility.]

So, given all that, why did I forsake the northern Arthur?

Maybe for no good reason! To begin, I had become fixated (as so many have) on identifying Uther with a figure found in the Welsh genealogies. We Arthurians are all, I think, made more than a little nervous by our concern over the validity of Uther's name. It is really the name of Arthur's father? Or is it merely a conjured one? Was uther (W. uthr) chosen for no other reason than it provided decent poetic assonance? We all know the play on Arthur and the word aruthr (ar- + uthr, 'very terrible'). It is entirely conceivable that Arthur's father's name wasn't known or had been completely forgotten and so someone had to make one up.

I, therefore, sought a connection for Uther that I could feel confident about. The 'pen kawell' of the MARWNAT VTHYR PEN, meaning literally 'Chief(tain of the) Basket' tied in very nicely with Ceawlin of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, whom I had previously identified as Cunedda (as ceawl in Old English also means basket). There appeared to be much of Cerdic of the Gewissei in Arthur, and Cerdic himself was Ceredig son of Cunedda. Their respective floruits matched. This yanked Arthur from the north to the south. I was still allowed my link to the Roman name Artorius through the relationship of the Seguntienses of Segontium/Caervarvon with Illyricum and the Welsh insistence that Arthur's kin came from nearby Dinas Emrys (= Caer Dathal). The dragon of Uther could be accounted for by the Dinas Emrys dragons, probably themselves a reflection of the military standard of the Seguntienses unit.

At the same time, I had dispensed with my placement of Arthur and Uther at the Ribchester Roman fort of the Sarmatians. This came about due to two discoveries. First, Eliwlad son of Madog son of Uther ended up belonging at Nantlle in Gwynedd, not at Ribchester. This Madog was not the son of Sawyl Benisel. Second, extensive research spanning many months proved to my satisfaction that Lucius Artorius Castus was in Britain before the Sarmatians ever got there, and had nothing whatsoever to do with the latter. Thus a Ribchester connection with LAC or the name Artorius was no longer a defensible idea.

I had also decided against making anything out of the corrupt TRIAD text that gave us an Arthur son of Eliffer of York. While York had been the headquarters of LAC as camp prefect, and the Dalmatian-manned Praesidium (according to Professor Roger Tomlin probably the civilian settlement outside the York fort) was hard by, Arthur son of Eliffer was a purely literary ghost and all the other Arthurian associations seemed to be firmly attached to Hadrian's Wall. Uther Pendragon as gorlassar matches only one other figure in Welsh tradition, and that is the great Urien of Rheged. This last is also called gorlassar. But adopting him as Arthur's father destroys our Arthurian timeline. Still, even this cannot be discounted entirely. My research into Urien showed he was given titles almost identical to that of Uther, and he was closely associated with the god Mabon. Mabon is the servant of Uther, etc.

What to do with all this, then? When we seriously study the Arthurian sources, and in particular the pre-Galfridian ones, we are met with a bewildering plethora of conflicting/competing/

We can always come up with problems with our own pet theories, if we are honest enough with ourselves. For example, the Uther elegy poem's 'pen kawell' can be rendered in two additional ways. It can mean 'Chieftain of [a place called] Cawell' or 'Chieftain of the Sanctuary.' There are several places in Britain composed of the word Cawell or at least containing it. They stretch from the River Cale in Somerset up through northwestern-most Wales to Kingscavil in West Lothian, Scotland. 'Chieftain of the Sanctuary' is incredibly tempting, as in the line in question we are told that Uther is transformed by God. We can make a very strong case for God being the 'Pen Kawell.' Either option negates my idea that the Chief Basket = Ceawlin of the Gewissei.

Uther Pendragon can be parsed any number of ways, depending on what one is trying to do with the name/title. I once proposed it was a Welsh rendering of the Roman rank magister utriusque militiae. As this rank was held by the British commander Gerontius in the early 5th century, I was able to claim that Arthur's father was one of the later Dumnonian Geraints who had either adopted this title for himself or who had been mistakenly given it during the course of story development. This notion was at first greeted with great excitement, as it allowed for us to retain the tradition of an Arthur of the Southwest (Tintagel, Domelick at St. Dennis, Kelliwic, Brean Down, South Cadbury Castle, Glastonbury, River Camel, etc.). But, alas, it collapsed horribly when it came to assigning the battles to such a man.

We Arthurian enthusiasts also seem to enjoy identifying Arthur himself with someone else. I've done it more than once in my research/writing career. Truth is, Arthur is Arthur. There is no justification, within the constraints of the context, for giving him another name. If he is Cerdic/Ceredig, we need a source that names an individual bearing both of those names. We lack such a source in each and every case. We are no better off trying to translate Arthur's 'dux erat bellorum' title into a Brythonic name or an epithet lurking in a poem. That exercise is just as futile.

It is obvious that the Northern Arthur should be revisited. In addition, I must entertain the notion that if the Northern Arthur continues to make the most sense in the broadest terms, then I must be willing to let go of the built-in need to isolate and analyze Uther's historicity. It may prove to be enough that we look to Birdoswald as the home of the partly Dacian-descended, draco-bearing chieftain, a terrible magister draconum who sired a son named after the Dalmatian Artorius of Carvoran.

Do we require more than this? Or will this do?

Stay tuned...

Stay tuned...

[1]

ARTHURIAN BATTLE SITES

Mouth of the Glein - Northumberland Glen

Dubglas River in Linnuis - Devil's Water at Linnels near Corbridge

Bassas - Dunipace

Coit Celidon - Forest at Caddon Water

Castello Guinnion - Binchester Roman fort

urbe Legionis - York

shore of the Tribruit - trajectus at North Queensferry

Mount Agned/Breguoin - Bremenium/High Rochester Roman fort, rebuilt by the governor Egnatius

Badon - Buxton

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)