Roman Empire under Commodus

A few days ago I wrote the following piece:

In it, I pointed out that a well-known unit bearing a British name was found in the Pannonia Inferior of Plotianus, a man implicated in a possible coup attempt against Commodus. It is thought that one of Perennis's sons was leading the legion in Pannonia Inferior. What I suggested, albeit extremely tentatively, is that the British unit in question may have been the soldiers mentioned in Herodian, and that the British spearmen in Dio were a mistaken, confused reference to these men. In other words, no soldiers came from Britain; it was members of a British unit that came from Pannonia Inferior.

While an interesting idea, it really didn't have any weight. As Professor Roger Tomlin noted, at best it might point to a source of some of the muddle surrounding the conflicting accounts of Perennis' downfall.

In this post I wish to put forward another idea, one which might bring us some clarity on the issue.

Quite some time ago, Prof. Tomlin and I discussed the problem of the fragmentary records for one Caunius Priscus:

This man had been legate of the Sixth legion in Britain when his troops tried to raise him to the purple. He wisely refused and was promptly shipped off to become legate of another legion. He may well have fought in the Deserters' War, although the British troops he was once thought to have used were more likely Germans. But in providing a speculative reconstruction of his career, Tomlin proposed that he may have been responsible for killing Maternus. For accomplishing this deed he was promoted.

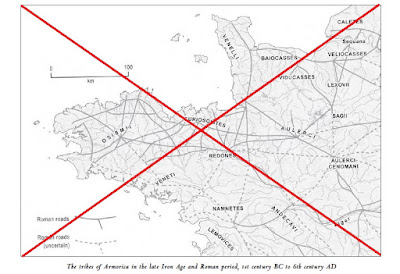

The possibility entertained by Tomlin made me think again about the 1500, for they, too, have been implicated in actions against the deserters. Typically, this is done by looking at the ARM[...]S of the Castus inscription as representing ARMORICOS, and accepting that the deserters Castus was fighting were located in that part of Gallia Lugdunensis.

Putting aside for a moment LAC's possible involvement as dux with the 1500 spearmen, let us look at the 1500 spearmen in isolation from LAC and from a different perspective.

Most scholars are unwilling to entertain Herodian's account of Maternus' desperate gambit to assassinate Commodus in Rome during a festival. But while the account may have fictional details, certainly it is not a strain on our credibility to allow yet another assassination attempt being made on the Emperor's Life. So let us start by assuming, for the sake of argument, that Maternus did make it through to Rome.

Let us now tweak Dio's account of the 1500 ever so lightly. As it is incredibly difficult - if not impossible - to explain how such a force could have marched straight to Rome without encountering any resistance, how about we do this instead: this force of British legionary detachments went to Rome after Maternus. Now, I realize this may not be a new idea. [In fact, I may have read it somewhere and just don't recall the source!] But it is a decent one, as it is not beyond the realm of the possible.

We may now combine this new scenario with Herodian's account of Perennis' fall. Either the Pannonian soldiers who got wind of the plot of Perennis brought about his downfall or those who had hunted down and destroyed Maternus did. In either case, the latter group was already in Rome. They could easily have approached Commodus - an man who seems to have proclaimed himself 'Felix' after the execution of Perennis - and aired their complaints about his Praetorian Prefect. These complaints would have included the removal of the legates in Britain, unpaid donatives to the victorious troops there, etc. If at the same time Perennis was being accused of conspiracy from the other quarter, i.e. from the Pannonian one, then a grateful Commodus might well have acceded to the wishes of both parties. Indeed, he would have felt pressured to do so, whether he personally believed the charges and wanted Perennis gone or not.

I think this quite a reasonable paradigm.

Bearing this in mind, let us now return to the question as to who it was commanding the 1500 British spearmen. If it were, indeed, LAC, and he is referring to this action on his memorial stone, what in the world do we do with ARM[...]S?

I recalled a discussion I had with Professor Roger Tomlin quite some time ago. In any effort to find any possible way that we could allow for the proposed reading ARMATOS for ARM[...]S, I asked him what LAC might have called the "mixed mob" [1] that comprised the followers of the deserter Maternus, whose Deserters' War took place during the reign of Commodus. Might he have resorted to ARMATOS for this rag-tag army?

His response:

"Your idea that Castus might have referred to a 'mixed mob' as ARMATOS is possible, and a good one, but I would like to find another instance. The weight of evidence is against it, as you know: you know the arguments as well as I do. There are so many specific terms he might have used: DEFECTORES, REBELLES, LATRONES, HOSTES PVBLICOS, PRAEDONES, even DESERTORES. I think of Tib. Claudius Candidus, legate of Hispania Citerior, et in ea duci terra marique adversus rebelles hostes publicos.

Trouble is, Castus is so explicit elsewhere in his great inscription that I can't think he would have been so vague at the highpoint of his career. And armatus, unlike all the nouns I have quoted, is an adjective – it is used of a person doing something illegal (but specified), and worse than this, doing it 'under arms'. Can you find armatus being used by itself in the sense of 'illicitly armed'. I had a quick look at the dictionary, but I couldn't find it in this sense – only neutrally, 'having arms' and then explicitly, being a 'soldier'.

We need 'someone doing something which is illegal' – and, still worse, doing it 'with weapons'. I wondered if armatus is used in the sense of doing something which is not only illegal but done 'with weapons'. But what this is, must be specified. For example, armed robbery."

But here is where we encounter another problem: most specific terms for the followers of Maternus would be fraught with potential built-in error. For example, you can't call anyone but a deserter a deserter. Now, the AUGUSTAN HISTORY does have Deserters' War for this conflict, and Maternus had formerly been a soldier. But all these other elements in his "army" were not deserters. We have brigands, runaway slaves, freedmen, freed prisoners (all kinds of criminals), gladiators, poor, peasant farmers, etc. If all of them were engaged in brigandage, even on a large scale, they could have been referred to as LATRONES or PRAEDONES. The only other term that could have been used to cover every member of such a disparate group would be HOSTES PUBLICOS, "Enemies of the State."

This means that LAC would not have had to resort to the use of an extraordinarly vague blanket term like ARMATOS to describe the followers of Maternus. ARM[...]S of his inscription has to stand for something else.

All of which brings us back to Caunius Priscus. I had argued against his leading British troops on the Continent against the deserters because he had only recently been pulled from Britain after his troops tried to raise him to the purple. It seemed illogical to assume that anyone would a short time afterward appoint him to command the very troops he had been hastily removed from!

But, it is certainly possible that the British troops brought over were from the other legions, not the Sixth, or the rebellious members of the Sixth had been dealt with, and so the danger that I imagined might lie in such an arrangement was not, in fact, present at all. If so, this would allow us to have Priscus be the one who pursued Maternus to Rome and to have participated also in the Fall of Perennis.

When I asked Tomlin if it were likely that Castus as dux would have taken British troops to the Continent to fight the deserters, only to put those troops under the command of Priscus, who was then terms praepositus of those troops, he replied:

"Difficult that someone should be sent off with vexillations from his province, only to relinquish their command to someone else. He would only come under the command of the army-commander whose army he had reinforced, as would have been the case had Castus led men out of Britain to serve under the other Priscus [Statius Priscus]."

[1]

As was noted by the abovementioned Herodian, Maternus had served in

the Roman army before he became a deserter and a criminal. Unfortunately

we do not know what formation and in which detachment he served.

Academic works on this topic, which will be discussed later, also offer

only some suggestions. To return to the initiated desertion, he managed to

convince to it also other soldiers who were probably his comrades in arms

(commilitiones). Then, with their support, after a short time he organized

a unit (manus) which – apart from the deserters – included runaway slaves,

poor peasants, but also criminals of different sorts. Moreover, he succeeded

in significantly increasing these forces in a few years.

From the Roman soldier, Maternus turned into a ‘commander-ringleader

of criminals’ (dux latronum / factionum-quasi imperator?). While wanting

for his companions (commilitiones) to create a harmonious and effectively

cooperating collective, he had to share his spoils with them (particularly,

including the stolen money) fairly. Having acted this way he managed to

win over probably not only their trust but, what is more, also encourage

others to join the ranks of his ‘criminal detachment’, and then most likely

– detachments (vide manipulos factionis – manus / cohors latronum). It is

highly unlikely that Maternus did not impose on the ‘latrones’ who were

subjected to him some set of rules and guidelines of conduct – rooted in an

oath made in the name of gods – which can be generally defined as a kind

of a ‘bandit law’ (leges latronum)27. Without accepting the type of rules

determining the mutual correlations and authority requirements – not to

mention the elementary loyalty towards each other – they could not carry

out their criminal activity in the long term and, even more so, function

within an increasingly larger community that with time started to form

around Maternus. Predatory raids which ended successfully, including

even those on large town centres, and the actions of opening local prisons

by force during the attacks, resulted in the ranks of Maternus’ ‘latrones’

getting continually bigger. However, apart from the freed prisoners, as

Herodian emphasised, Maternus had to be joint also by others, for whom

the idea of great booty and the promise of a fair participation in it were

stronger than the fear of a severe punishment they could expect if they were

arrested as ‘latrones’28. Thus, he will be accompanied not only by successive

deserters from the Roman army but also runaway slaves, freedmen and

poor, free-born farmers (plebs rustica). As can be guessed, Maternus’

forces which were numerically strengthened in this way, amounting from

several hundred to a thousand or more people, could intensify the scale of

criminal attacks being carried out, including the plundering and burning

even of larger cities of Gaul and the Iberian Peninsula29.

The necessity of supplementingthe losses in the ranks of the Roman army units –

which was a result of extremely difficult Marcomannic wars – engendered a situation

where in the second half of the 2nd c. AD recruits who should not have been accepted

in the army had been enlisted. This refers to i.e. freed slaves, including

gladiators, and the so-called brigands-criminals (latrones) from the territories

of Dalmatia and Dardania. And this was not only about a particularly low

socio-legal status of these soldiers, but – what was even worse – about the

lack of their proper mental preparation in order to cope with hardships and

rigours of military service that were imposed on them in the Roman army.

This was not changed even by the fact that they could ask to be volunteers

(volones) themselves. Therefore, as was noted by Anthony Birley, groups of

runaway slaves and deserters who wandered around Gaul, Spain and Italy9

were the remnants of the Marcomannic wars.

.JPG)