I've been asked by a correspondent a rather uncomfortable question:

"How can you be so sure that Illtud as Uther Pendragon was not wrongly substituted for Sawyl Benisel as Arthur's father? It would be great if you could treat of this possibility sometime in one of your blog posts."

The question is uncomfortable for a variety of reasons. First, I had already acknowledged that this kind of thing could have happened - or that Uther Pendragon (whoever he was!) may have been utilized as Arthur's father because the hero's real parentage was unknown or had been forgotten.

Second, the appeal of Sawyl of Ribchester is strong, for all the reasons I brought up in earlier research. Arthur's battles are easily put in the North without manipulation due to supposed "translation" errors. And, in truth, some of these battles are hard to dislodge from the North (the Tryfwyd/Tribruit being a good example, as the PA GUR situates it at Queensferry near Edinburgh). We have all kinds of wonderful correspondences, such as the Camboglanna fort on Hadrian's Wall, just a few miles east of Aballava/Avalana ('Avalon'?) fort. An Arthur from Ribchester of the Sarmatian veterans allows us to propose a preservation of the Artorius name due to interaction of the Roman period Sarmatian troops in Britain with L. Artorius Castus (who may have led some of them in the Deserters' War and to Rome itself to demand the removal of the Praetorian Prefect Perennis). The Sarmatians are noted for their dedication to the draco standard, something that might have contributed to the idea that Arthur's father had something to do with the dragon. We should also not forget that like Uther, Sawyl had a son named Madog. Etc.

And Arthur son of Illtud, on the other hand, loses all of that. He does gain what might well be spurious Welsh tradition that seems to connect him with Ergyng and a 'Llydaw' adjacent to that early Welsh kingdom. I have provisionally identified this Llydaw and Illtud's father Bicanus with Lydbrook and Welsh/English Bicknor in what was, in fact, Ergyng. This seemed an exciting development, as the Lydbrook and Bican- place-names are duplicated right at Liddington Castle/Badbury in Wiltshire. This seemed an effort to connect Arthur with a 'Badon.' Alas, Welsh tradition is split on the location of Badon. The Welsh Annals seem to point to Liddington Castle as the scene of the so-called Second Badon, while 'The Dream of Rhonabwy' firmly situates the site at Buxton in the High Peak, an actual Badon/Bathum in early English sources. Buxton is perfect for the Ribchester Arthur. Needless to say, an Arthur at Liddington, which may have given its name to the nearby settlement of Durocornovium (perhaps the origin of Arthur's 'Cornwall'), creates a scenario for his battles that finds us once again having to match them up with those of Cerdic of Wessex and subsequent members of the Gewissei. Camlan as an intact, preserved place-name goes away in the South, as does Avalon (unless one accepts the fraudulent claims of Glastonbury!). According to what we have on Illtud, the saint had no children and had even put away his wife.

At this point in our exploration of the problem of Illtud vs. Sawyl as Arthur's father, it would be best to review the relevant source material. What follows are selections from the Lives of St. Illtud and St. Cadoc, respectively, followed by a passage from Geoffrey of Monmouth's HISTORY OF THE KINGS OF BRITAIN and, lastly, some important lines from the 'Marwnat Vthyr Pen' or 'Death-song of Uther Pen[dragon].'

§ 3. Of the household of king Poulentus, which the earth swallowed up, and of the promise made to adopt the clerical habit after military service at the advice of St. Cadog.

It happened on a certain day, when he was conducting the royal household for hunting through the territory of saint Cadog, while it rested, it sent to the renowned abbot in stiff terms that he should prepare for it a meal, otherwise it would take food forcibly. Saint Cadog, although the message seemed to him improper owing to the harshness of the words, as though demanding tribute from a free man, nevertheless sent to the household what sufficed for a meal. This having been sent, the household sat down with a will to take the meal, but the willing came short of the eating. For on account of the unlawful demand and sacrilegious offence the earth swallowed up theunrighteous throng, which vanished away completely for such great iniquity. But Illtud the soldier and master of the soldiers escaped, because he would not consent to the unjust demand, nor was he present in the place where the household had been in order to wait for the food, but was far off holding a she-hawk which he frequently let go and incited after birds.

§16. Of the robbers swallowed up in the earth.

To this miracle another not unlike did the divine power perform to declare the merits of the blessed man. There was a certain chief, named Sawyl, living not far from his monastery, who, full of evil affections, arrived with his accomplices at his abode, and violently took from thence food and drink, both he and all his followers eating and drinking in turn, whilst the clergy groaning at such infamy and shame entered the church, for the monastery at that time happened to lack the presence of the man of God, and devoutly supplicated the Lord for the castigation (or the cutting off) of the invaders. And whilst they were weeping with great lamentation, lo, the holy man arrived suddenly, and diligently inquired of them the cause of so much sorrow. After they had related the reason he says to them with unchanged countenance, ‘Have patience, for patience is the mother of all virtues. Suffer them to steep their hearts in debauchery and drunkenness, so that being drunk they will fall into heavy sleep together. Then, when they are oppressed with sleep, shave off with sharpest razors the half part of their beards and hair as an eternal disgrace against them, and also cut off the lips of their horses and their ears as well.’ And they did as he had bidden them. Then the wretched brigands, having somewhat digested in their sleep the superfluity of what they had consumed, and at length having waked, being stupid with excessive drinking, mount their steeds, and begin their journey immediately. Then the man of God said to his clergy, ‘Let each one of you put on his clothing and shoes to go to meet them, or ye will perish in death, for our enemy will return and will slay us with the sword from the greatest to the least, when he snail perceive that he was mocked by us.’ Therefore they each put on their clothes, and saint Cadog clothed himself with his garment, and there followed him nearly fifty clerics to meet the deadly tyrant with chants and hymns and psalms. And when they ascended a certain mound, Sawyl Benuchel and his satellites descended to meet them. Then before the eyes of the servant of God the earth opened its mouth, and swallowed up the tyrant alive with his men on account of their wickedness, lest they should cruelly murder the man of God with his clergy. And the ditch, wherein they were swallowed up, appears to this day to all passing by, which, always remaining open as a witness of this affair, is not allowed to be closed in by any one.

VII. Hengist is beheaded by Eldol.

Aurelius, after this victory, took the city of Conan abovementioned,

and stayed there three days. During this time he gave

orders for the burial of the slain, for curing the wounded, and for the

ease and refreshment of his forces that were fatigued. Then he

called a council of his principal officers, to deliberate what was to

be done with Hengist. There was present at the assembly Eldad,

bishop of Gloucester, and brother of Eldol, a prelate of very great

wisdom and piety. As soon as he beheld Hengist standing in the

king’s presence, he demanded silence, and said, “Though all should

be unanimous for setting him at liberty, yet would I cut him to

pieces. The prophet Samuel is my warrant, who, when he had Agag,

king of Amalek, in his power, hewed him in pieces, saying, As thy

sword hath made women childless, so shall thy mother be childless

among women. Do therefore the same to Hengist, who is a second

Agag.” Accordingly Eldol took his sword, and drew him out of the

city, and then cut off his head. But Aurelius, who showed

moderation in all his conduct, commanded him to be buried, and a

heap of earth to be raised over his body, according to the custom of

the pagans.

Neu vi a elwir gorlassar:

It’s I who’s styled ‘Armed in Blue’:

vy gwrys bu enuys y’m hescar.

my ferocity snared my enemy.

5 Neu vi tywyssawc yn tywyll:

It is I who’s a leader in darkness:

a’m rithwy am dwy pen kawell.

Our God, the Chief Luminary, transforms me. [1]

Neu vi eil Sawyl5 yn ardu:

It’s I who’s a second Sawyl in the gloom:

ny pheidwn heb wyar rwg deu lu.

I’d not give up without bloodshed [the fight] between two forces.

Legendary Poems from the Book of Taliesin,

edited and translated by Marged Haycock,

CMCS Publications, Department of Welsh, Aberystwyth University, 2007.

Now, perhaps the most important thing to point out is that the Welsh elegy on Uther betrays absolutely zero influence from Geoffrey of Monmouth. On the other hand, the poem's use of gorlassar as an epithet for Uther (it is thought to mean blue enameled weapons and/or armor and is used also of Urien of Rheged in the Book of Taliesin) and the presence of God as Chief Luminary (with the word canwyll having the figurative meaning of 'star') strongly suggests that Geoffrey mined this source when concocting his story.

Less clear is why Geoffrey associates Eldad (= Illtud) with the Biblical Samuel. Being a cleric, he may have been familiar with the Lives of Cadoc and Illtud, and knew that Sawyl took the place of Illtud in Cadoc's Vita. That alone would have been enough for him to have Eldad refer to himself as being like Samuel, as the author's highly creative, synthetic approach to story-telling would naturally have availed itself of the opportunity. He clearly had not derived Samuel from the Sawyl of the Uther poem. If he had, he would know Uther was Illtud/Eldad. I can think of no good reason why he would have decided, in that case, to arbitrarily separate out Arthur's father into two distinct personages.

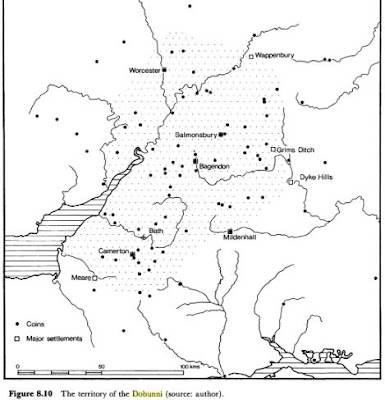

Let's look closer at the Sawyl found in the Life of St. Cadoc. He is said to live not far from the saint's Llancarfan. There was clearly confusion over the various Sawyls. The Northern one is, in the earliest records, called Benisel. This Southern one is, instead, Benuchel. Later we find the Northern one taking on the Benuchel title. It is entirely possible that due to the traditional interpretion of Llancarfan as 'church of the stags' [2] (more probably, according to John Koch, it is from carban, from a Proto-Celtic *karbantom ‘chariot’), Sawyl of Ribchester was transferred through the usual folkloristic process from the North to the South. This may have occurred because Sawyl's brother Cerwyd[d] was the eponym for the Carvetii tribe of Cumbria, upon whose southern border lay Sawyl's kingdom, the territory of the Roman period Setantii tribe. Carvetii meant something like 'the stag-people.' Sawyl Benisel is said to have been swallowed by the earth at Allt Cunedda only because that place has ancient tumuli and is hard by a Llancadog.

There was a St. Sawel in Carmarthenshire (formerly under Cynwyl Gaeo, Ystrad Tywi), although nothing is known about him. However, there was a Mabon the Giant who had a castle at Llansawel. Mabon in the 'Pa Gur' is the servant of Uther Pendragon. The following is from P.C. Bartrum's A CLASSICAL WELSH DICTIONARY:

< MABON GAWR. (Legendary).

One of four brother giants said to have dwelt in Llansawel in Ystrad Tywi. His place was called

Castell Fabon. (Peniarth MS.118 p.831, ed. and trans. Hugh Owen in Cy. 27 (1917) pp.132/3). The

others were Dinas Gawr and Wilcin Gawr and Elgan Gawr. See the names.>

It may be, therefore, that the Sawyl of St. Cadog's Life is, in fact, Sawyl of the North - a chieftain relocated to Wales in folk tradition.

A final word on the Uther elegy is called for. The word 'eil' can mean either 'like' or 'a second'. So we could have a reading of "It's I who's like Sawyl in the gloom" instead of "It's I who's a second Sawyl in the gloom." But either way, it's important for us to bear in mind that Uther becomes a Samuel only metaphorically. This is poetic language. God makes Uther to be like the Biblical Samuel in battle. Yet these poems are replete with references to myth and magic, and a reader might well have thought that Uther really had been transformed into a Samuel.

This being so, here is my question:

Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that Arthur's real father was Sawyl Benisel. Is it reasonable to postulate that Illtud/Uther Pendragon was mistakenly believed to have been identified with Sawyl - an error derived from a misintepretation of the elegy lines - and that the two chieftains were further conflated by the conflicting accounts of Illtud and Sawyl in the saints' Lives? And, if this happened, might Uther have come to replace Arthur as his father in the southern Welsh tradition?

The whole thing comes down to this: Uther and Sawyl had sons named Madog. Illtud did not.

So, was Sawyl merely brought into Illtud's orbit because Illtud was poetically compared to the Biblical Samuel?

OR was Illtud wrongly identified with Sawyl, Arthur's real father, because the former had been poetically linked to the Biblical Samuel?

As always, I will ponder all of the above for a decent spell before reaching a conclusion as to who has the best chance of being Arthur's father .

[1] My translation, made with the assistance of Dr. Simon Rodway of The University of Wales and Prof. Peter Schrijver of Utretcht. The sequence tywyll/kawell (for kanwyll)/Sawyl (for kawyl) is the only possible rendering for these lines, given the rhyming constraints of the poem.

[2]

§12. Of the return of the blessed Cadog to his principal monastery.

Then the blessed Cadog, when he had perceived that he was effectually imbued with liberal instruction, commending his oratory to his teacher Bachan and some of his followers, returned to his own abode in his dear country, to wit, Llancarfan. Another miracle of the same venerable father is said to have occurred. For when he had returned to his own town of Llancarfan, whence he had long withdrawn, seeing his principal monastery destroyed, and the timber of the roofs scattered rudely over the cemetery, he grieved at the downfall, burning to build it anew with God’s permission. Therefore, all his clergy being summoned, and some workmen, he went with them all to a wood to fetch a supply of timber, except two youths, namely, Finian and Macmoil, who with the leave of the man of God remained that they might have time for reading. Then suddenly the prior, the cellarer, and the sexton coming, scolded them, saying, ‘How long, being disobedient and doing no good, refusing to work with your fellow disciples, will you eat the bread of idleness? Come, hasten to the wood, and bring hither quickly a supply of timber with your comrades.’ They answer and say, ‘Can we draw wagons like oxen?’ Those showed them in derision a couple of stags standing by the wood, and proceed in this wise, ‘See, two very strong oxen are standing by the wood. Go quickly and lay hold of them.’ And they proceeding (or going) quickly, and leaving a book open, owing to their great hurry, where they were sitting, in the open air, ordered the stags in Christ’s name to wait for them, which, immediately forgetting their wildness and gently awaiting them, submit (or lower) their untamed necks to the yoke. They drive them home, like tame oxen, with a great beam attached to the yoke placed on the stags, which scarcely four powerful oxen could draw, and there allow them to return to their pastures detached from the yoke. Saint Cadog, seeing and greatly wondering at this deed, asked them, saying, ‘Who bade you to come over to me, and besides, having left off your reading, to devote yourselves to drawing timber?’ They narrated to him the reproaches of the three aforementioned men, who railed at them. He, inflamed with wrath, inflicted on the three aforementioned officers a curse after this manner, ‘May God do this to them, and more also, that those three persons die the worst of deaths, cut off by sword or famine.' Moreover, in that hour wherein these things happened, a shower fell from the sky throughout the whole of that region. Wherefore the man of the Lord asked the aforesaid disciples, where they had left their book. They fearing said, ‘Where we were sitting, employed in reading it, we left it open under the sky, having forgotten it in our great haste.’ The man of’ God, having gone there, found the book entirely uninjured by the rain, and greatly wondered. Therefore that book in memory of the blessed man is called in the British language Cob Cadduc, that is, Cadog’s memory. Also in the same place in honour of saint Finian a chapel is said to be situated, where his book was found dry and free from rain amid whirls of rains and winds. From the aforesaid two stags, yoked after the manner of oxen and drawing a wagon, the principal town of saint Cadog took from the old settlers of Britons the name of Nant Carwan, that is, Stags’ Valley, whence Nancarbania, that is, from ‘valley’ [nant] and ‘stag’ [carw].