In recent days, I wrote the following pieces:

Since then, I've been thinking more about the conflicting accounts of the downfall of Perennis, as well as what may be the truth behind his story. To help me with both, I first consulted The Fall of Perennis: Dio-Xiphilinus 72. 9. 2., A. Brunt, The Classical Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 1 (May, 1973), pp. 172-177 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/638138?seq=1). Then I went back to the primary sources themselves.

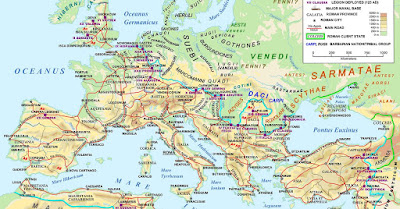

The first interesting detail that struck me was that in Herodian's version, it is not British soldiers who are the instrument of Perennis' death, but instead a conspiracy of Illyrian soldiers under the command of Perennis' sons. These Illyrian soldiers supposedly (HISTORIA AUGUSTA, Life of Commodus, 6.1) had won victories over the Sarmatians. If we go by Dio's account, it would appear the 1500 contus-bearing soldiers from Britains may be intended to represent Sarmatian cavalrymen.

Now, Herodian is generally considered to be little better than a historical romance. But the apparent coincidence of battles against Sarmatians in one place and the possible march of Sarmatians from another is certainly worth noting. It may well be that some kind of confusion has occurred in the various primary texts, a confusion that has combined British and non-British events that happened at or near the same time, a sort of conflation of history. The relevant passages from both the HISTORIA AUGUSTA and Herodian are posted here in full:

6 1 About this time the victories in Sarmatia won by other generals were attributed by Perennis to his own son.45 2 Yet in spite of his great power, suddenly, because in the war in Britain46 he had dismissed certain senators and had put men of the equestrian order in command of the soldiers,47 this same Perennis was declared an enemy to the state, when the matter was reported by the legates in command of the army, and was thereupon delivered up to the soldiers to be torn to pieces.48

45 According to Herodian, I.9, this son of Perennis, in command of the Illyrian troops, formed a conspiracy in the army to overthrow Commodus, and the detection of the plot led to Perennis' fall and death.

46 In 184. According to Dio, LXXII.8, the Britons living north of the boundary-wall invaded the province and annihilated a detachment of Roman soldiers. They were finally defeated by Ulpius Marcellus, and Commodus was acclaimed Imperator for the seventh time and assumed the title Britannicus; see c. viii.4 and coins with the legend Vict(oria) Brit(annica), Cohen III2 p349, no. 945.

Commodus was persuaded to put the prefect's sons in command of the army of Illyricum, though they were still young men; the prefect himself amassed a huge sum of money for lavish gifts in order to incite the army to revolt. His sons quietly increased their forces, so that they might seize the empire after Perennis had disposed of Commodus...

"Commodus, this is no time to celebrate festivals and devote yourself to shows and entertainments. The sword of Perennis is at your throat. Unless you guard yourself from a danger not threatening but already upon you, you shall not escape death. Perennis himself is raising money and an army to oppose you, and his sons are winning over the army of Illyricum. Unless you act first, you shall die."

There is a great deal of confusion about the actual sequence of events in Britain at this time, and much of it involves a certain Priscus. I have discussed this man before. He was of the senatorial class, and served as legate of the Sixth legion in Britain. After that term, he served as legate of the Fifth Macedonian legion. It was this latter legion that was often brought to bear against the Sarmatians, including under the reign of Marcus Aurelius. It again went against the Sarmatians early in the reign of Commodus (https://www.livius.org/articles/legion/legio-v-macedonica/). After this posting, he may has served as praepositus over vexillations of the British legions - although the reconstructed reading on his stone is considered highly conjectural, according to Professor Roger Tomlin. My analysis of the stone as found in Birley would concur with Tomlin's opinion. For more details on the Priscus inscription, see "Un nuovo senatore dell'età di Commodo?", Gian Luca Gregori, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik , 1995, Bd. 106 (1995), pp. 269-279 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/20189321). After this questional British posting, he goes on to become propraetorian legate of the Second Legion Italica.

Returning now to Dio Cassius' mention of Priscus:

2a The soldiers in Britain chose Priscus, a lieutenant, emperor; but he declined, saying: I am no more an emperor than you are soldiers"

The lieutenants in Britain, accordingly, having been rebuked for their insubordination, — they did not become quiet, in fact, until Pertinax quelled them, — now chose out of their number fifteen hundred javelin men and sent them into Italy. 3 These men had already drawn near to Rome without encountering any resistance, when Commodus met them and asked: "What is the meaning of this, soldiers? What is your purpose in coming?" And when they p91 answered, "We are here because Perennis is plotting against you and plans to make his son emperor," Commodus believed them, especially as Cleander insisted; for this man had often been prevented by Perennis from doing all that he desired, and consequently he hated him bitterly. 4 He accordingly delivered up the prefect to the very soldiers whose commander he was, and had not the courage to scorn fifteen hundred men, though he had many times that number of Pretorians. 10 So Perennis was maltreated and struck down by those men, and his wife, his sister, and two sons were also killed.

What we need to do now is to try and untangle this knot, many loops of which are hidden from our view. The only real evidence we have is the Priscus stone, despite its poor condition and hypothetical reading. Priscus may have been offered the purple when he was legate of the Sixth. This would seem to be the most logical moment for such a thing to have happened. It is unlikely the troops would have tried to make emperor a man who was sent to lead British troops on some special - and probably emergency - mission. Alfoldy (with Birley agreeing) suggested that Priscus was praepositus over British troops during the Deserters' War on the Continent. While this is possible, our records show the Maternus affair being dealt with by Pescennius Niger based at Lyon with the Eight Augustan Legion (https://www.livius.org/articles/person/pescennius-niger/). Commodus had made the call for troops from the provinces affected by the revolt, and Britain in not included in the descriptions of the Deserters' War (although from the time of the governorship of Ulpius Marcellus, Britain was in a mutinous state).

It is best at this juncture that I include the wonderful summary here from Anthony Birley's THE ROMAN GOVERNMENT OF BRITAIN. He is surely correct here in placing the attempted elevation of Priscus when the latter was actually legate in Britain.

"By the time of Marcellus’ victory, perhaps in reaction to his harsh methods, there was a mutiny, recorded in a fragment of Dio (72(73). 9. 2a)¹⁴³: ‘The soldiers in Britain chose Priscus, a legionary legate (Ëpostr3thgon) as emperor; but he declined, saying: “I am no more emperor than you are soldiers”.’ The dating is supplied by the HA: ‘Commodus was called Britannicus by flatterers when the Britons even wanted to choose another emperor in opposition to him’ (Comm. 8. 4). Priscus was clearly removed from his post (see LL 35), as were, apparently, the other legionary legates. Again, the HA supplies some information: ‘but this same Perennis [the guard prefect], although so powerful, because he had dismissed senators and put men of equestrian status in command of the soldiers in the British war, when this was made known by representatives of the army (per legatos exercitus), was suddenly declared a public enemy and given to the soldiers to be lynched’ (Comm. 6. 2). Perennis fell in 185, for ‘when [Commodus] had killed Perennis he was called Felix’ (Comm. 8. 1): Felix first appears in his titulature in that year.¹⁴⁴ As well as the legionary legate Priscus, a iuridicus can be identified who served under Marcellus, Antius Crescens, later acting-governor (Gov. 34). His appointment at a time when the governor was heavily occupied in the north fits the theory that the British iuridicus was not a regular official."

To help us fill in the time in question, here is what Birley has for Antius Crescens:

The acting-governorship of this man is known only from this fragmentary

inscription. An approximate chronology may be obtained, for he is also

named on three other, dated, inscriptions. Two at Ostia show his presence

there as pontifex Volcani in 194 and 203; the third, the Acta of the Saecular

Games of 204, attests his participation as a quindecimvir.¹⁴⁹ His tenure of that

priesthood is registered on his cursus inscription in what seems to be chronological

order. This led to the conclusion that his service in Britain, mentioned

next, must have come not long before 204. Early 203 was excluded, since he

was at Ostia on 24 March in that year, and it was assumed that he was actinggovernor

c.200 on the death or sudden departure of Virius Lupus (Gov. 37).¹⁵⁰

But nothing whatever is known about the end of Lupus’ governorship, so this

dating lacks any basis. Crescens was elected to the college after service in

Britain and before the proconsulship of Macedonia. But it does not follow that

he held these posts just before the games of 204. If he was praetor at the

normal age, 29, his service in Britain probably came when he was in his midthirties

(the cura of an Italian community and the legateship in a proconsular

province would not occupy more than three years or so). Hence he probably

became a quindecimvir at about 38. He could have remained an active member

for at least another twenty years.

Acting-governorships were the product of special circumstances, in most

cases (before the third century) the sudden death of the governor. Sometimes

an imperial procurator assumed the role, but there are several cases where a

legionary legate took over. One precedent in Britain is from the year 69, when

the legionary legates governed the province jointly after the flight of the

governor Trebellius Maximus (Gov. 7, cf. LL 8). Under Domitian a legionary

legate called Ferox (LL 12) may have been acting-governor after the death of

Sallustius Lucullus (Gov. 12). In 184 or soon after, when Ulpius Marcellus was

recalled, there were no legionary legates, as they had been replaced by

equestrians (see under Gov. 33). Hence it is plausible that Crescens was acting governor

for several months—as the only senator left in the province. He

presumably remained in post, the army still being mutinous, until the arrival

of Pertinax in 185.¹⁵¹

A quindecimvir died c.185, C. Aufidius Victorinus (cos. II ord. 183) (Dio 72. 11.

1).¹⁵² Calpurnianus could have replaced him—as a reward for meritorious

service in Britain. That might also explain his relatively rapid progress to the

consulship, after only one further post, as proconsul of Macedonia. By contrast,

Sabucius Major (iurid. 5), after being iuridicus of Britain not long before

Crescens, went on to be prefect of the military treasury, governor of Belgica,

and proconsul of Achaia, before becoming consul in 186.

Our sources declare that the mutiny in Britain was not quelled until the governorship of Pertinax, Marcellus' successor.

What next?

Well, if LAC led 1500 Sarmatian troops from Britain to Rome to get rid of Perennis, and he did it with detachments from all three British legions, he was performing the role (as Roger Tomlin has made plain) of either "acting-commander: pro legato" or "a prefect 'acting' for the legate, agens vice legati. These become legionary commanders in the second half of the third century, and in Egypt the legions were always commanded by equestrian prefects."

Well, if LAC led 1500 Sarmatian troops from Britain to Rome to get rid of Perennis, and he did it with detachments from all three British legions, he was performing the role (as Roger Tomlin has made plain) of either "acting-commander: pro legato" or "a prefect 'acting' for the legate, agens vice legati. These become legionary commanders in the second half of the third century, and in Egypt the legions were always commanded by equestrian prefects."

The answer as to who sent the deputation to Rome is provided in this source:

Such a man was Marcellus and he inflicted terrible damage on the barbarians in Britain; and after this he was almost at the point of being put to death by Commodus, on account of his special excellence, but was nevertheless pardoned.

Dio-Xiphilinus 72. 8. 1–6

On this pardon, Birley has this:

Dio does not make clear whether or not there was any appreciable interval between Marcellus’ victory and his recall, but it is plausible to suppose that it was the fall of Perennis, not to mention the mutinies, which led to Marcellus’ prosecution on his return. Of course, if he had really served uninterruptedly

from 177 to 185, his governorship would have exceeded even that of Julius Agricola (Gov. 11), exactly a century earlier. The replacement of the legionary legates by equestrian commanders would have meant that for a time the only senatorial official in the province was the iuridicus, who was made acting governor. Marcellus’ pardon was sufficiently complete for him to become proconsul of Asia, evidently in 189: he is actually described as ‘my friend’ by Commodus in a letter to the city of Aphrodisias.¹⁴⁷ Possible members of his family in later generations have been referred to above.¹⁴⁸

I would plausibly put forward that it was Ulpius Marcellus who was held responsible for LAC's mission to Rome. However, it was probably Priscus the legate of the Sixth who sent LAC. Again, LAC was acting as the agent of the legate.

Now, this leaves open the question of Priscus' possible use of British troops after his posting as legate with the Macedonian legion. I would make this later use of British troops to have happened after "Pertinax requested the emperor to send a replacement, since the legions resented his restoration of discipline (Birley)." "It is probable that an unknown governor was Pertinax’s immediate successor (Birley)." That governor was followed by Decimus Clodius (Septimius) Albinus.

If the proposed reconstruction of the Priscus stone is correct, he was praepositus of vexillations of three British legions. Now, a praepositus is a temporary, ad hoc commander. LAC had himself held this position with the fleet of Misenum. The strange thing about Priscus holding this rank is that he had twice before been legionary legate, and then was legionary legate again. His being appointed as a temporary commander for detachments of British legions must mean that he was needed to deal with some kind of emergency. If we do not permit this to be action in the Deserters' War on the Continent (in A.D. 185-186-7, with Maternus' attack on Argentoratum happening at the turn of July and August 185 and Perennis's death in April–May 185; see https://journals.umcs.pl/rh/article/viewFile/9556/8305), then we can only assume he was needed either during the quashing of the British rebellion by Pertinax or immediately after, in the interval between Pertinax and Albinus. Pertinax had barely escaped with his life, and the legions were still unruly. Perhaps the praepositus here was, literally, filling the gap in the governorship. Priscus was legate of the Sixth had been beloved enough of his troops for them to try and make him emperor. Perhaps his presence in the province later was designed to have a calmative effect, as he would be more likely to gain the allegiance of the mutinous troops.

Who was the unknown governor who took over from Pertinax?

Well, whoever it was, it cannot have been LAC. Whether he was governor or acting-governor, that is something he would have placed on his memorial stone between his role as dux in the Perennis affair and his serving as procurator of Liburnia. We cannot interpret dux as being the equivalent of governor. This has been demonstrated time and time again, and I will not repeat the reasons why this is so in this post. In the second century, and in the Antonine period, dux meant simply a leader or general of a special task force. In addition, we know of an equestrian in Hadrian's time who was appointed procurator of a newly divided Dacia. So there is no difficulty in accepting that LAC had been a legionary legate prior to his posting in Liburnia - especially when we remember that he was almost certainly born at Salona. Once again, and I emphasize this to the nth degree: had LAC been governor of Britain, he would have said so on his stone. To expect anyone prior to the mid-third century to know that dux meant provincial governor is not possible. That kind of ambiguity is not something LAC would ever have done when trying to pass done his life's accomplishments to posterity.

I will conclude with this brief treatment of LAC's military ranks with a wise comment from Professor Roger Tomlin:

"The Valerius Maximianus inscription is almost the same date. He is careful to specify that he was raised to the senate before being made a legionary legate. LAC never says this. LAC never pretends to be anything other than a prefect of a legion, and the dux designation merely serves to show that he was a prefect performing the role of agens vice legati. If he were more - say, a legate, or a provincial governor - he would absolutely have put that on his stone. Indeed, he would have screamed it to the world!"

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.